The Stack

/I’m going to tell you guys a secret.

Well, it’s not really a secret. It’s more of a personality trait that I prefer not to share with the world, but that always, inevitably end up falling into the public domain category: I’m the most technologically challenged person you’ll ever meet in your life. No one is worse than me when it comes to technology.

If you’re wondering how my secret always ends up being revealed, it’s usually when someone asks me: “hey, what’s your Instagram?”, only to hear me say: “mmm…I don’t have an IG account”. The reaction to my reply varies. It can go from a sarcastic “dude, under which rock have you been living all this time?” to an incredulous “whatchu mean, you ain’t got no IG?!”

There are other less mundane, albeit not less embarrassing, examples. Like that day when a friend of mine from work came to my office so we could have lunch together, and I told him I wouldn’t be able to make it because I had to go to the bank to pay some bills. That was in 2012, when everyone was already USING THEIR PHONES to pay their bills!

He went: “dude, ever heard of online banking?”. I said yes, but I also said that I didn’t know how to use it. He kindly offered to help me out. Off we went. I accessed my bank’s website, logged in and everything. Finally, we got to the step where I was required to enter some kind of password. He asked: “what’s the password?” I said: “I have no idea”. Refusing to give up, he said: “well, call the bank then. Ask them. We ain’t getting outta here until you learn how to use this freaking thing!”

I called the bank and a voice response unit answered. I pressed a bunch of numbers, until I finally heard the message “enter your password”. Apparently, it was a different password, one that was to be used on phone calls only. Obviously, I had no idea what that password was either.

Needless to say, I had lunch by myself on that day. ;o)

That being said, I believe it will come as no surprise for you when I say that, up until August 2020, I had only heard of Netflix. I had never accessed Netflix’s website, let alone watched any of its content.

All I knew was that it was a streaming service. And truth be told, I didn’t even understand the concept of a streaming service. To me, it made no sense: watching videos was something people did on Youtube. And if everyone could watch videos on Youtube for free, why would anyone pay for a private service to do so?

Well, that question was quickly answered when, just as my dear friend had done by teaching how to use online banking services in 2012, my sister (very generously) decided to bring her brother back from the Stone Age all the way to 2020, by sharing her Netflix account with me, thus introducing me to the wonderful and fantastic Netflix universe.

Today, just a few months later, I understand why so many people are into Netflix.

And by “so many people”, I mean over 200 million people around the globe. That’s right. In January 2021, Netflix crossed the 200 million subscribers barrier. That’s pretty much Brazil’s entire population. And we’re talking about paid subscribers, only. We’re not even considering all the other people with whom these subscribers share their accounts.

Now, here’s an interesting question.

On the one hand, we have an audience of hundreds of millions of people that account for a total of 190 countries. On the other hand, we have a company that needs to address all of these people, who live in different countries, speak different languages and come from different cultures.

Is there a way to make sure that communication efforts will (somewhat) be one and the same across all these different markets?

Yes, there most definitely is. Some call it brand books. Others call it branding guidelines. As the name states, a brand book is – essentially –, the brand’s “manual”. Its purpose is to regulate everything that has to do with the way the company speaks to its customers: from tone of voice and typography to which kind of photos and color palettes should be used.

Every global company has one. Cocoa-cola does. Google does. Unilever does. Uber does. They all do. And with Netflix, it’s no different.

What IS, however, refreshingly different in Netflix’s case is that its brand guidelines offer a conceptual approach.

Those were the exact words spoken by Ryan Moore, creative director at Gretel, the NY agency responsible for developing Netflix’s current branding guideline. According to an interview that appeared in the Fast Company magazine:

“The big challenge was unifying everything, (…) the brand itself was a little fractured because they were working with partners and agencies around the world. (…) What they needed was an idea to stitch everything together – a conceptual approach –, (…) a visual system all these agencies could look at and adapt to any format they needed to”.

The concept chosen to inspire this brand book was that of “selection and curation”.

Why? (remember how with concepts, there’s always a reason-why? ;o))

Because Gretel wanted us to know that Netflix is, indeed, a movie catalog. But first and foremost, it’s someone who’s responsible for curating everything we watch, handpicking and recommending the most exciting, relevant, fun and customized options for us.

Pretty great, right?

What’s even greater is the way the agency managed to turn this concept into a brand book. But before we get into that, I’d like to first focus on Ryan Moore’s words, specifically the ones highlighted in bold.

He said the big challenge was unifying everything. Now, why was it a challenge?

In order to fully understand why, perhaps a bit of context might help: in 2015, when Gretel was hired for the job, Netflix was operating in 65 countries. However, it had already laid out an expansion plan that was going to be set in motion on the very first days of January 2016: Netflix was going to double its market reach from 65 to 130 countries.

The challenge Moore was referring to was this: how could Gretel help Netflix double its global presence from 60 to 130 countries without compromising the integrity, coherence and unity of its visual and textual communication materials?

In other words: how could Gretel unify everything?

The answer came in the form of an idea. A concept.

Which doesn’t surprise us, creatives, at all. At least, it shouldn’t. After all, one of the most valuable qualities of a concept is its ability to equalize people’s understanding. We use concepts to help people:

Understand the world around them and

Understand each other.

In case this last paragraph ended up sounding a bit confusing, here’s an example that might clear things up.

This sister of mine, the one that introduced me to the wonderful world of Netflix, is herself and endless source of great stories. It’s like she was issued a passport instead of a birth certificate when she was born: she’s been traveling around the world ever since she was a young teenager, and she’s probably the most cultured person I know. During one of her travels, she ended up in Madagascar. And when she came back, she mentioned the majestic Baobabs.

I was like: Bao-what? What’s that?

Instead of Googling it, I decided to guess.

Could she be talking about members of a tribe, like the Himbas in Namibia or the Konsos in Ethiopia?

Or was she referring to some kind of unique species endemic to the largest island in the African continent, like fossas and ring-tailed lemurs?

What was my sister talking about? What the heck was a Baobab?

She finally enlightened me: it’s a tree.

All of a sudden, the seas parted. Everything started making sense. Now, we were on the same page.

By using the concept of tree, suddenly, we started understanding each other. I started to fully comprehend what she was talking about because I started using the same concept as her: “oh, I see. Ok, we’re talking about trees”. From that point forth, we were functioning in the same wavelength. We equalized out understanding.

It just so happens that in that particular case, we were speaking about a Baobab. And I am intentionally using the word “particular”.

If you’re reading this post, then you’ve passed by the introduction above and already know that this blog is named after Plato, the guy from the cave.

Besides being the guy who created the Allegory of the Cave, he is also the guy behind one of the most beautiful and dramatic theories ever produced by Western Philosophy: the Theory of Forms. According to this theory, Plato states that the universe is comprised of “forms” and “particulars”.

(No, no. Don’t leave me hanging here just yet! I know this sounds nerdy and boring, but I’ll be super quick! I promise! ;o))

Plato

Socrates’ student.

Aristotle’s teacher.

The guy from the cave.

And the theory of forms.

The Theory of Forms is quite simple (despite its absolute brilliance). According to it:

There’s the “form of tree” (which is the “concept of a tree”, the idea we have of a tree)

And there’s a “particular tree” (that’s why I used the word particular before): for example, a Baobab, a Sequoia, a Pine, a Eucalyptus, etc.

You might not know what exactly a Sequoia is. But if I tell you it’s a tree, you’ll understand, right?

For exemple, let’s say we’re having a nice conversation over dinner. At some point, I say the word “tree”.

I don’t know which tree, in particular, you are thinking about. But I do know that its form is probably made of a vertical trunk, a few branches here and there and a canopy of some sort on top.

That’s it. Pretty simple, right?

There are forms. And then, there are particulars. (Ok, done! See? I told you it was going to be quick! ;o))

Concepts are the forms.

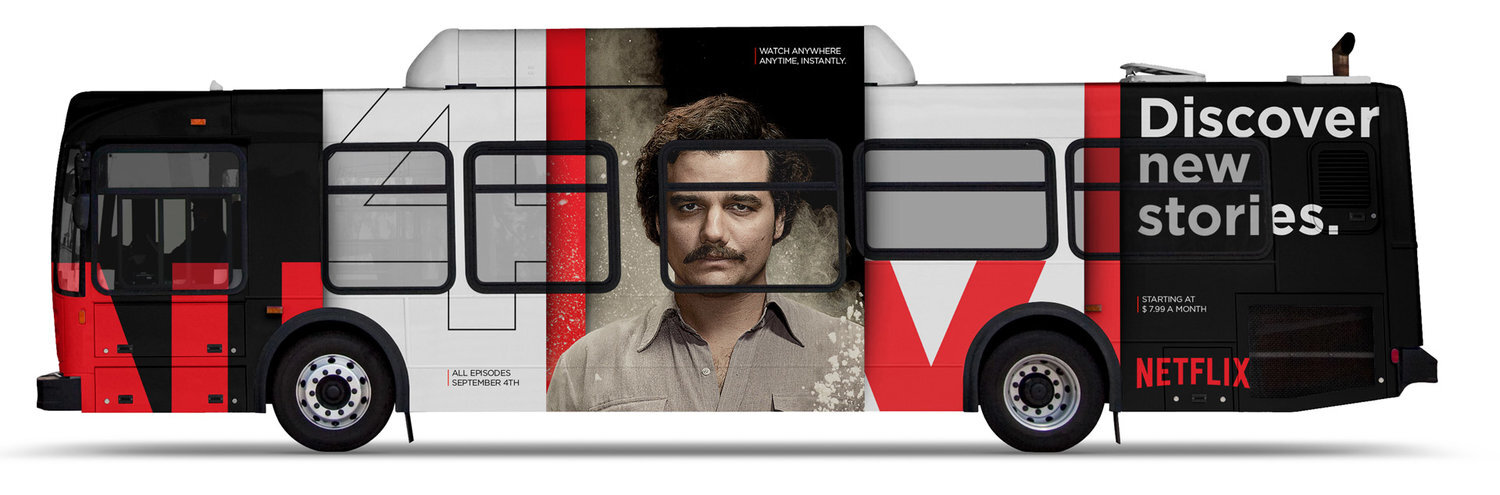

And the way Gretel turned the concept of selection and curation into a brand book was particularly great: they called it The Stack.

The idea behind The Stack is this: imagine three cards, disposed just like in the video below.

Now imagine that each of these cards represents a movie, a show, a series or a documentary from the Netflix catalog.

Finally, and this one’s for you guys who excelled at combinatorial analysis in school, please do the math: considering Netflix’s entire catalog, how many possible combinations do we get by mixing these three cards up?

I don’t really know the answer, but if I had to guess, I’d say it’s something close to “infinite”. And that’s exactly what Gretel wanted us to pick up from The Stack: that Netflix is indeed an endless, living catalog of shows and movies, always expanding. In other words: there’s always something else to see.

Also, Gretel knew it would be simply impossible to oversee every single creative, designer and art director working for Netflix’s communication around the world. So, instead of creating a branding guideline with a million rules and regulations, down to the tiniest detail, Gretel decided to operate from the camp of guiding principles. Directives, if you will.

These directives were related to the role that was assigned to each card.

One had to feature a photograph or video of a“character”

One had to be entirely dedicated to a splash of one the Netflix’s colors (black, white or red)

One was reserved for a text of some sort (like a movie title or tagline)

That’s it. Nothing else. How these cards would be intertwined, the “width” of each card, how they would be animated, all that was entirely up to the designer. End of story. It doesn’t get any simpler than that.

Such simplicity was quickly rewarded.

As soon as the new brand book was launched, positive reviews started coming from critics all over the world. Logo Design Love (the website) described it as “one of the strongest and most comprehensive identities of recent times”. Fast Company (the business magazine) called it “a universal branding language that can scale from giant billboards to tiny iPhone apps.”

The ultimate proof of The Stack’s huge success came in 2018, when Netflix was voted the simplest brand in the world, according to the “Simplicity Index”, beating brands such as Google, McDonald’s and Spotify. The ranking is based on criteria such as “how easy the company’s services are to use”, “how honest customers perceive the company’s industry to be” and, most importantly, “how clear the brand’s identity is”.

The “Simplicity Index” was created and is managed by branding firm Siegel+Gale, who is also responsible for taking care of brands such as 3M and HP, and for creating the iconic NBA logo.

Speaking of logos, Netflix’s logo, besides being a masterpiece in simplicity, is also incredibly conceptual: Cinemascope, the process created in the late 50’s and that made the projection of films in widescreen mode possible, was the inspiration behind it. The choice of red and black also has a reason-why: according to Netflix, these colors were deliberately chosen because they create a premium cinematic feel.

I love this about concepts: the fact that everything has a reason-why. But here’s something else that I also love (and admire) about the conceptual world: the fact that concepts are unifiers. They’re timeless. And universal. A tree is a tree no matter where you are in the world. It’s always been and always will be.

In that sense, come to think of it, concepts are kind of the opposite of technology, which changes all the time, everywhere. And therefore, tends to divide more than it tends to unify.

Don’t believe me? Well, let’s take the concept of social media.

Apparently, today, “old timers” use Facebook. “Young people” use Instagram.

Yesterday, it was all about Snapchat; today, it’s all about Tik Tok.

In Brazil, we use WhatsApp. In China, they use WeChat.

Technology changes.

The concept doesn’t: we’re still talking about social media.

It’s the same, for both “old timers” and “young people” (unifier).

It’s the same, yesterday and today (timeless).

It’s the same, from Brazil to China (universal).

That’s why it’s always been easier for me to understand and navigate the conceptual world than it was to keep up with the fast-paced and fickle rhythm of the tech universe. But that doesn’t mean I don’t see all the benefits and advantages that come from technology. No, no. On the contrary. I’d be the first to acknowledge them. There are plenty of them.

For example: learning how to use the Internet to access online banking services - as hard as it was (for someone slow and lame like me) -, brought me an enormous benefit. And it’s not even the fact that I don’t have to waste my time waiting in line to pay my bills anymore.

It’s because I can spend more time watching Netflix. ;o))

Please, give it up to… The Stack.