Concept vs. Idea

/What’s the difference between a “concept” and an “idea”?

Go to the dictionary, any dictionary, and it will tell you these words are synonymous.

And they are… to a certain extent.

The reason I say this is because yes, a concept IS – indeed – an idea.

But – at least to me – it’s a very particular kind of idea, in that there’s a sense of…. well, for lack of a better word, “FINALITY” to it.

I can explain.

Take the concept of “LOVE”, for example.

As an idea, “love” is a very foundational kind of idea.

There’s something definitive about it.

It’s a fundamental idea.

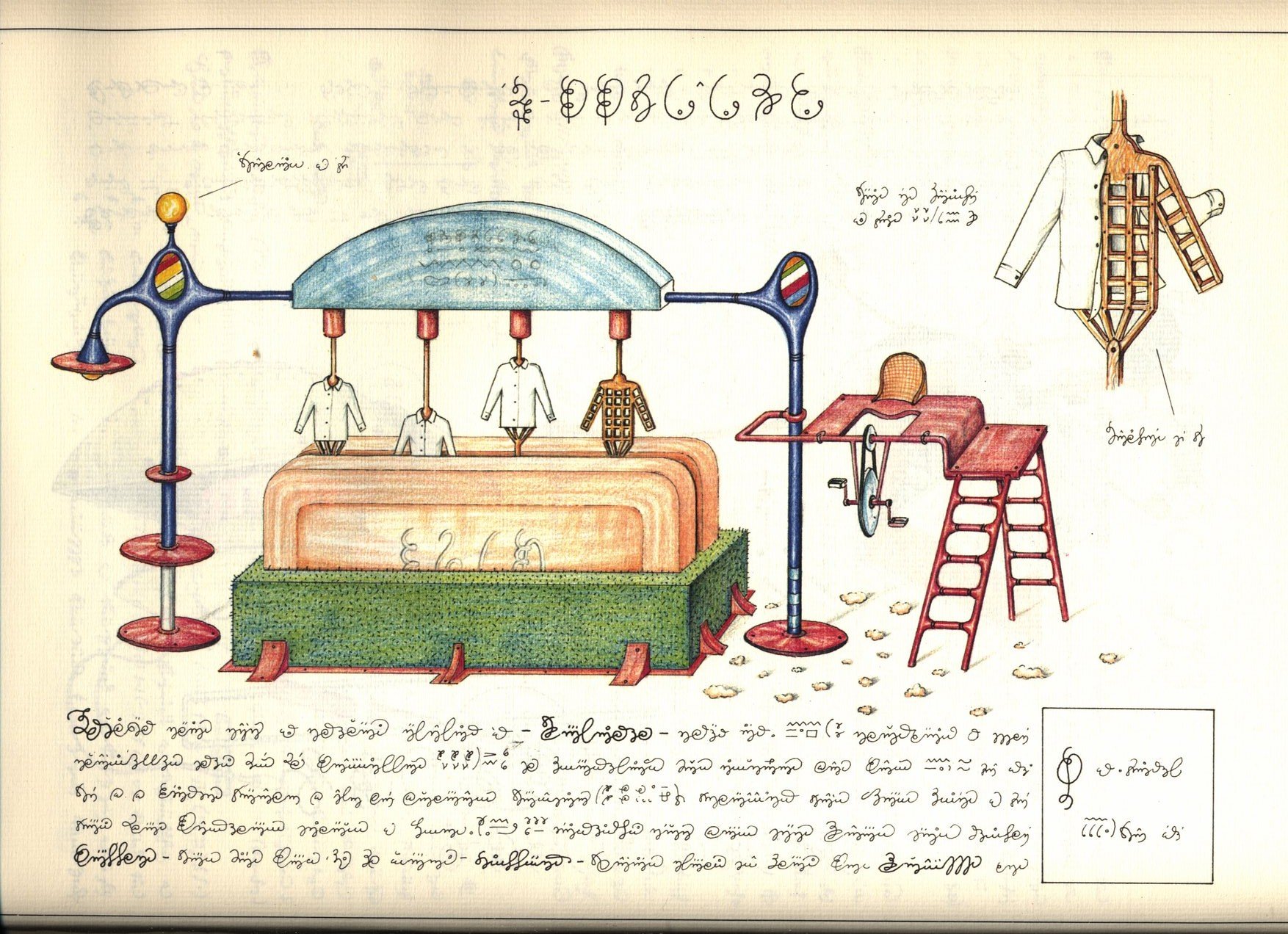

That’s probably why we use concepts to explain things to children.

Concepts, after all, help children make sense of the world around them.

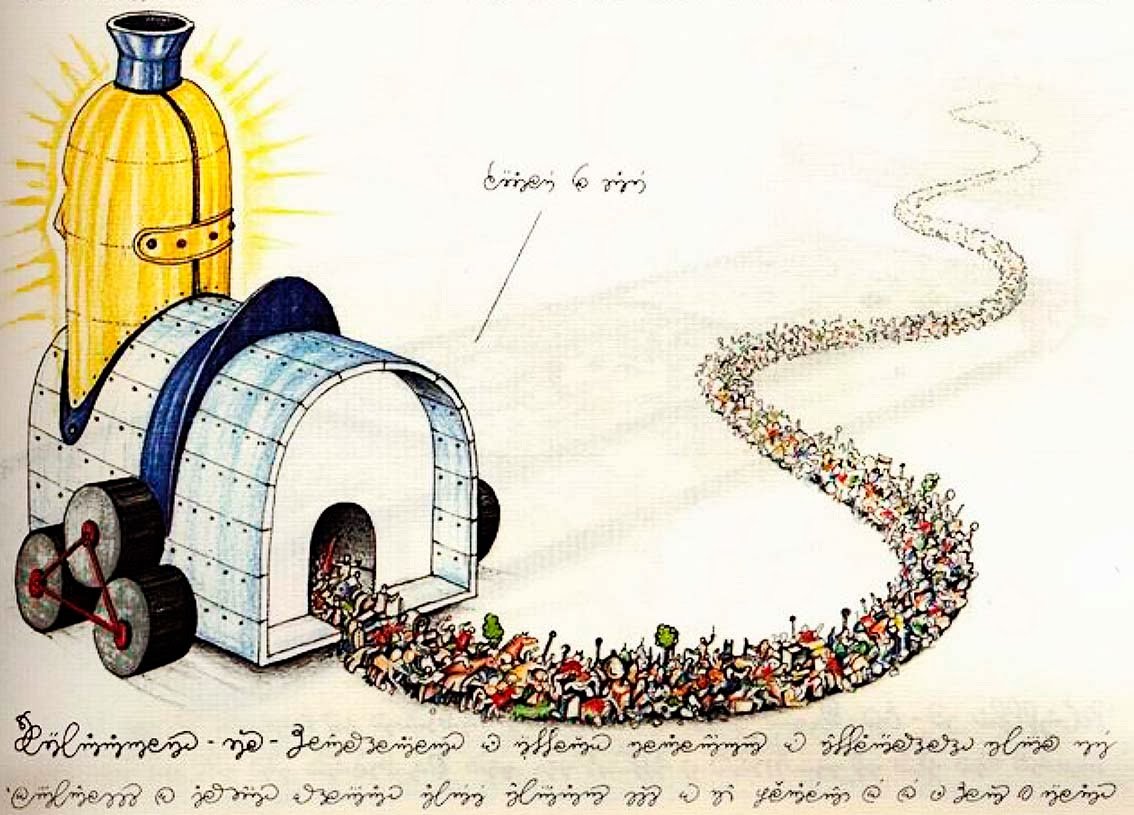

But something very strange, and beautiful, happens once a concept is assimilated.

Suddenly, all bets are off.

Nothing is off limits.

Every idea counts.

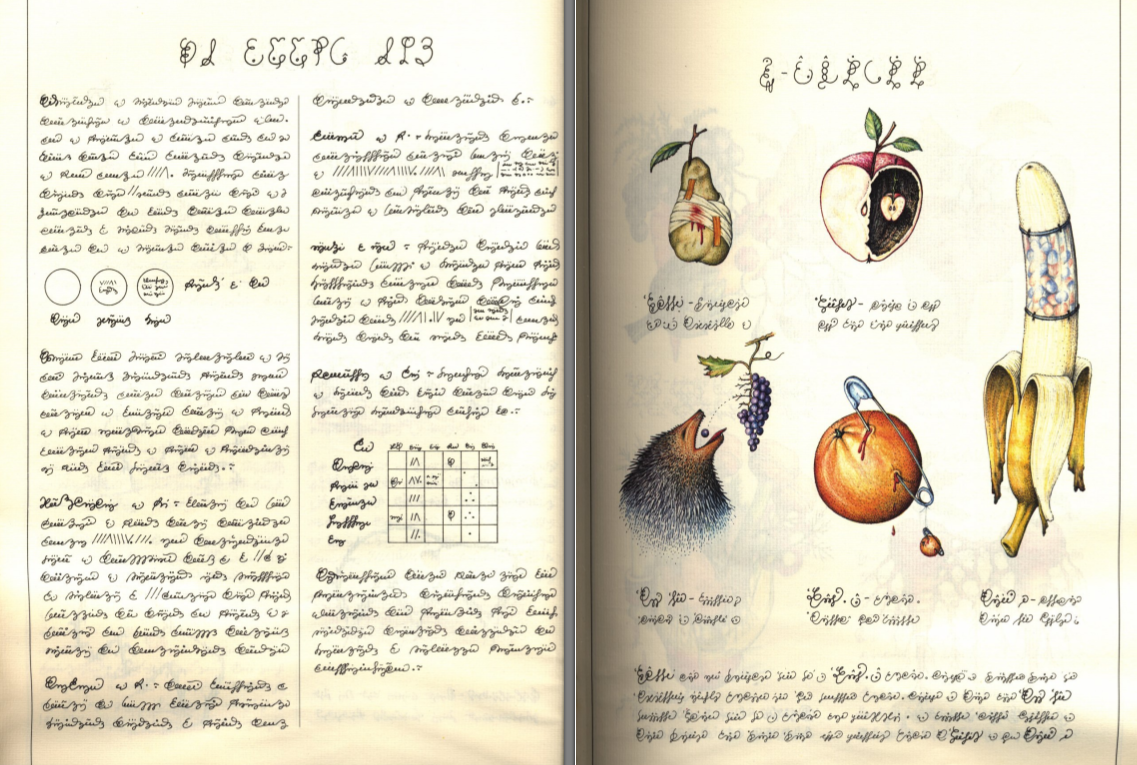

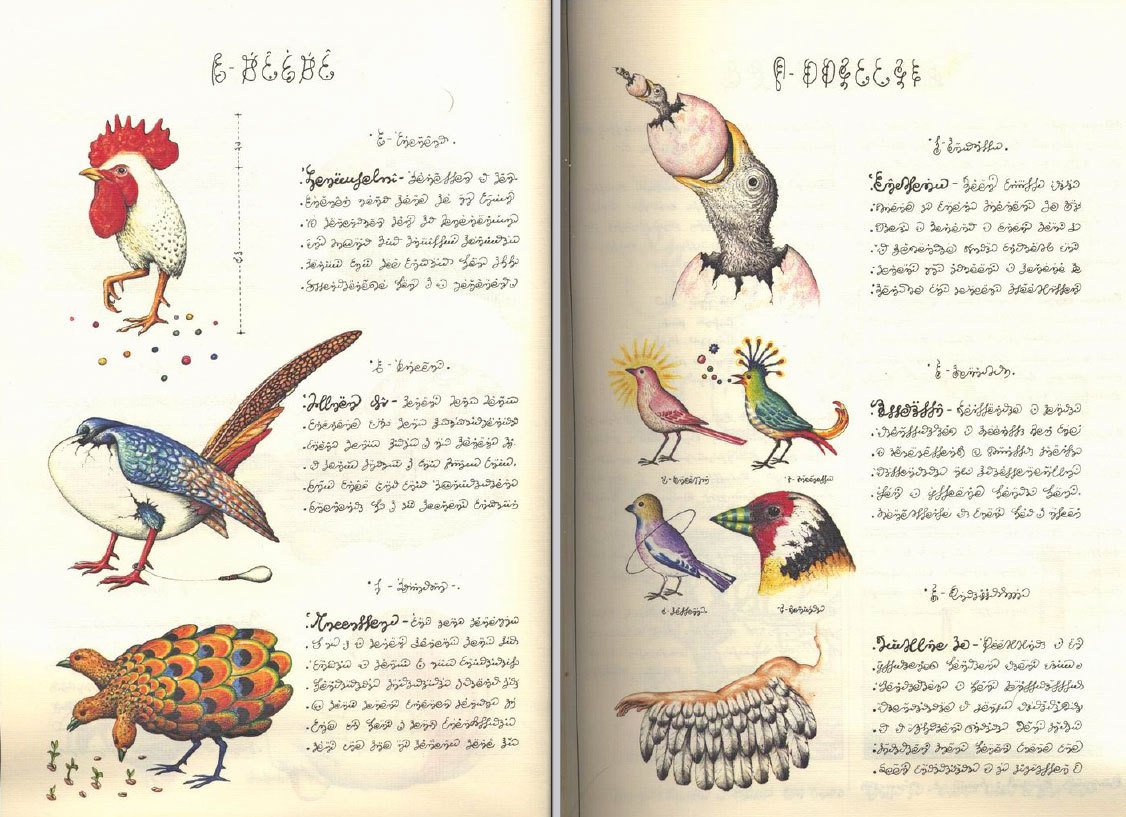

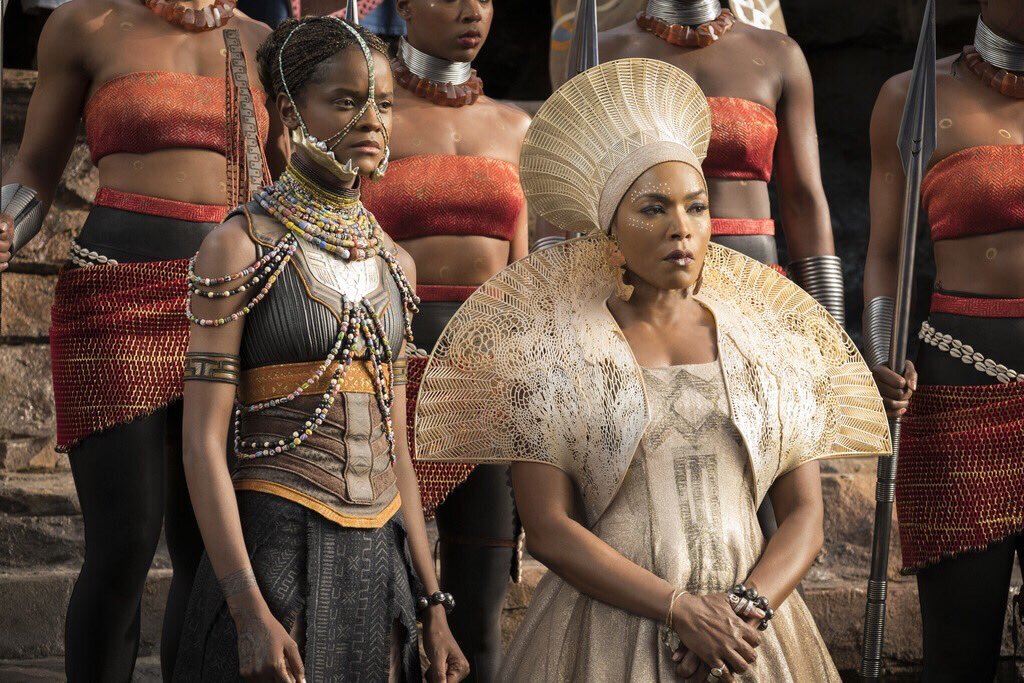

Take the concept of “elephant”, for instance.

A child who grows up watching Disney movies may have a “Dumbo idea” of an elephant.

French children, on the other hand, may have a “Babar idea” of an elephant.

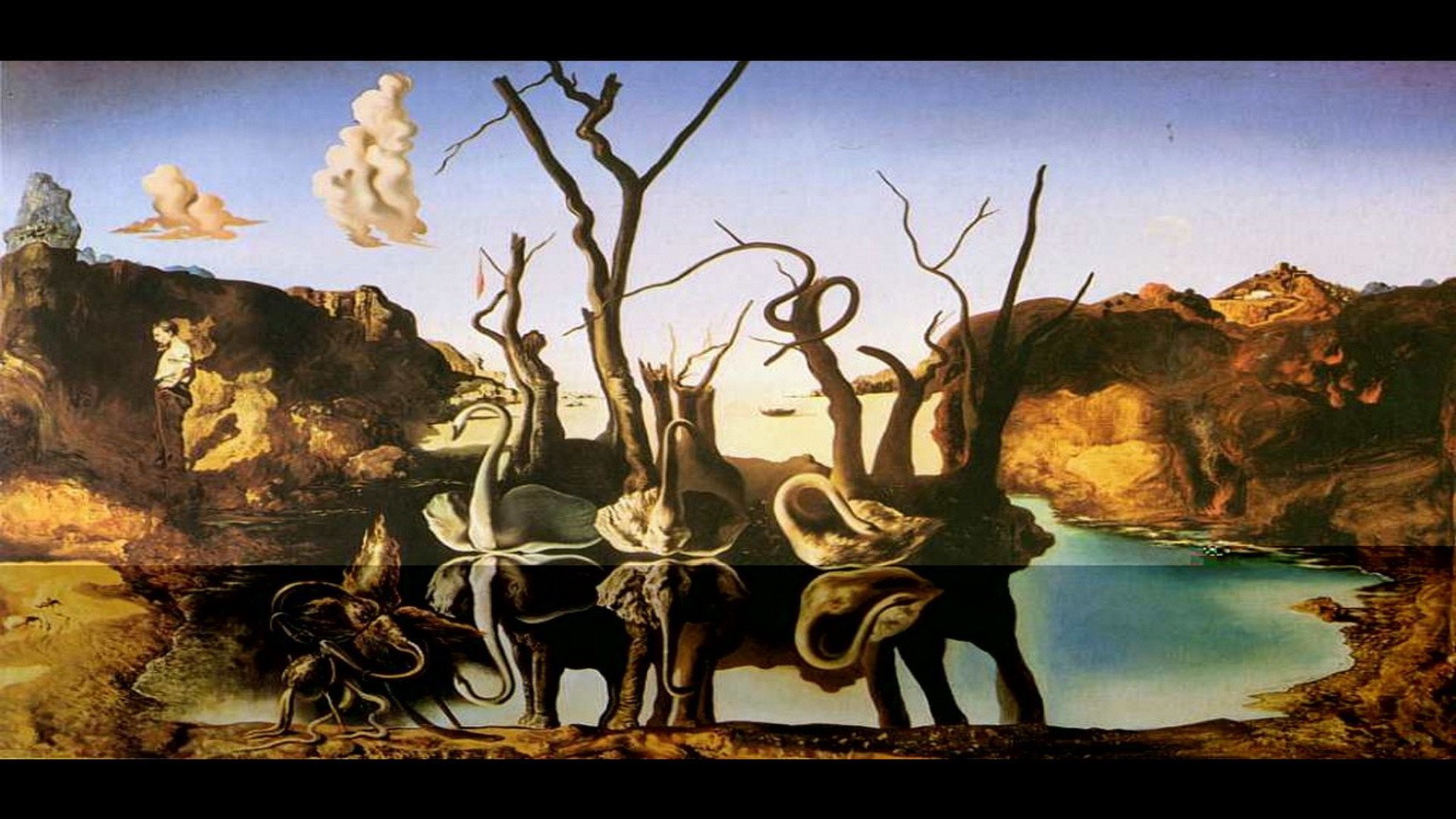

And then there’s Dali, who somehow had a “Swan idea” of an elephant.

They’re all drawing from the SAME concept.

But they all have DIFFERENT ideas of this concept.

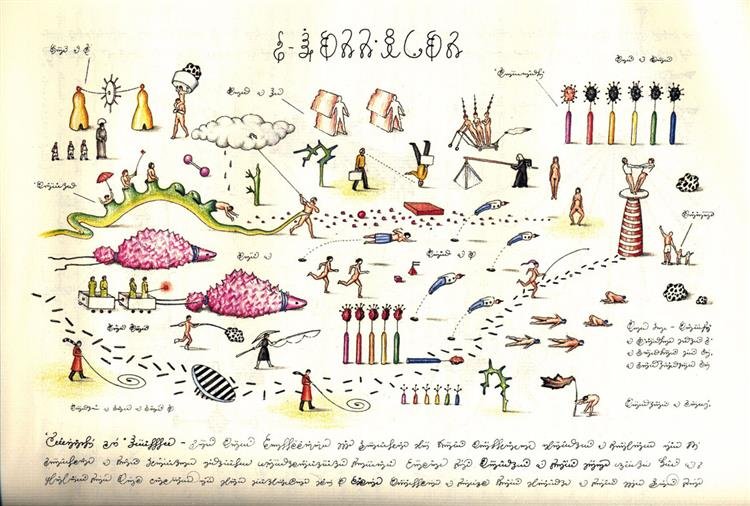

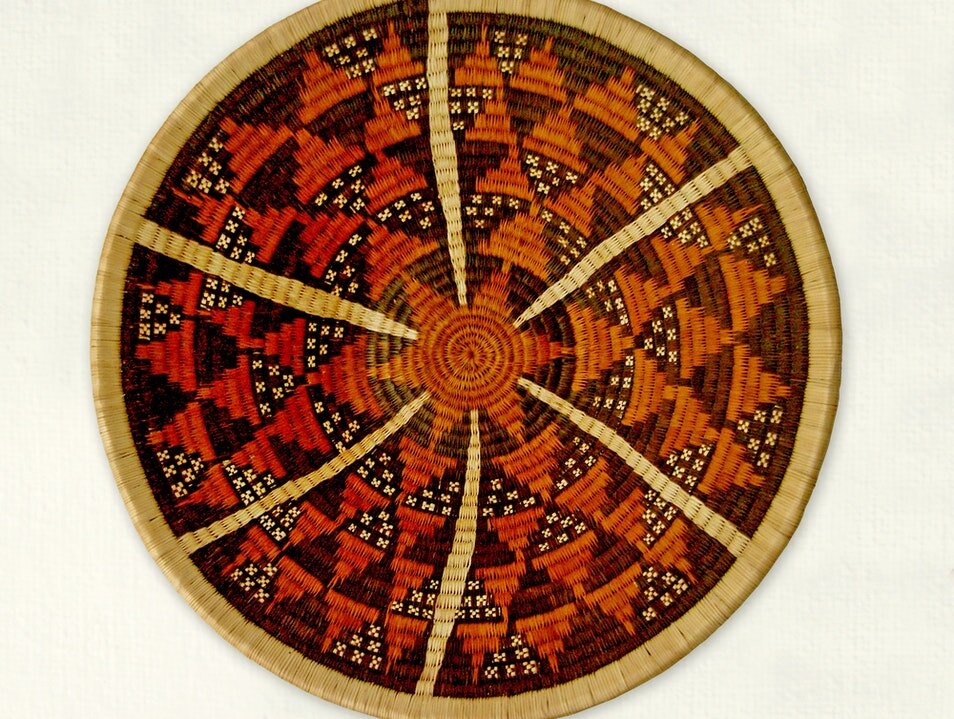

In that sense, an idea is like water.

It comes in many ways, shapes and forms.

Because it is endlessly free flowing in nature.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that (and again, at least to me and in my eyes only):

An idea is… infinite.

A concept is… definite.

And making that distinction is extremely important, in terms of creativity.

Make sure to check out the next post to find out why (ooohhh, cliffhanger… ;o))

See you there!

PS: Oh, and before I forget: happy 2023, everyone! It’s good to be back!