Utterly Original

/Lately, I’ve been thinking about something that’s been keeping me awake.

As human beings, do you guys think we’re able to deliberately and wilfully conceptualize something that’s utterly original?

By UTTERLY original, I mean:

Something that is NOT inspired by ANY previous references.

Let me give you guys an example of what I mean by that. For the longest time, I considered Van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) to be utterly original (given that I know nothing about art, you can understand why…;o)). That was until 2005, during the “Vincent Van Gogh: The Drawings” exhibition at the MET in NY, when I learned that it was actually inspired by Hokusai’s Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1831).Something that is NOT a combination of other existing things.

Some say a unicorn is an original creature. And it is. But is also – and ultimately – nothing more than combination of a “horse” (an existing thing) and a “horn” (another existing thing).Something that is NOT simply an evolution of something else.

Companies such as Uber, AirBnb and Netflix, which ARE original services, can’t be considered UTTERLY original (at least, in my eyes) because, in essence, they’re simply an evolution of taxi, hotel and video rental services.

Notice that my question wasn’t if we were able to INVENT or DISCOVER something utterly original. That, we can. Of course we can.

Sometimes, these inventions and discoveries happen by accident: gravity (Isaac Newton), penicillin (Alexander Flemming) and, yes, of course, the greatest invention of all, the kickflip (Rodney Mullen), are perfect examples of it.

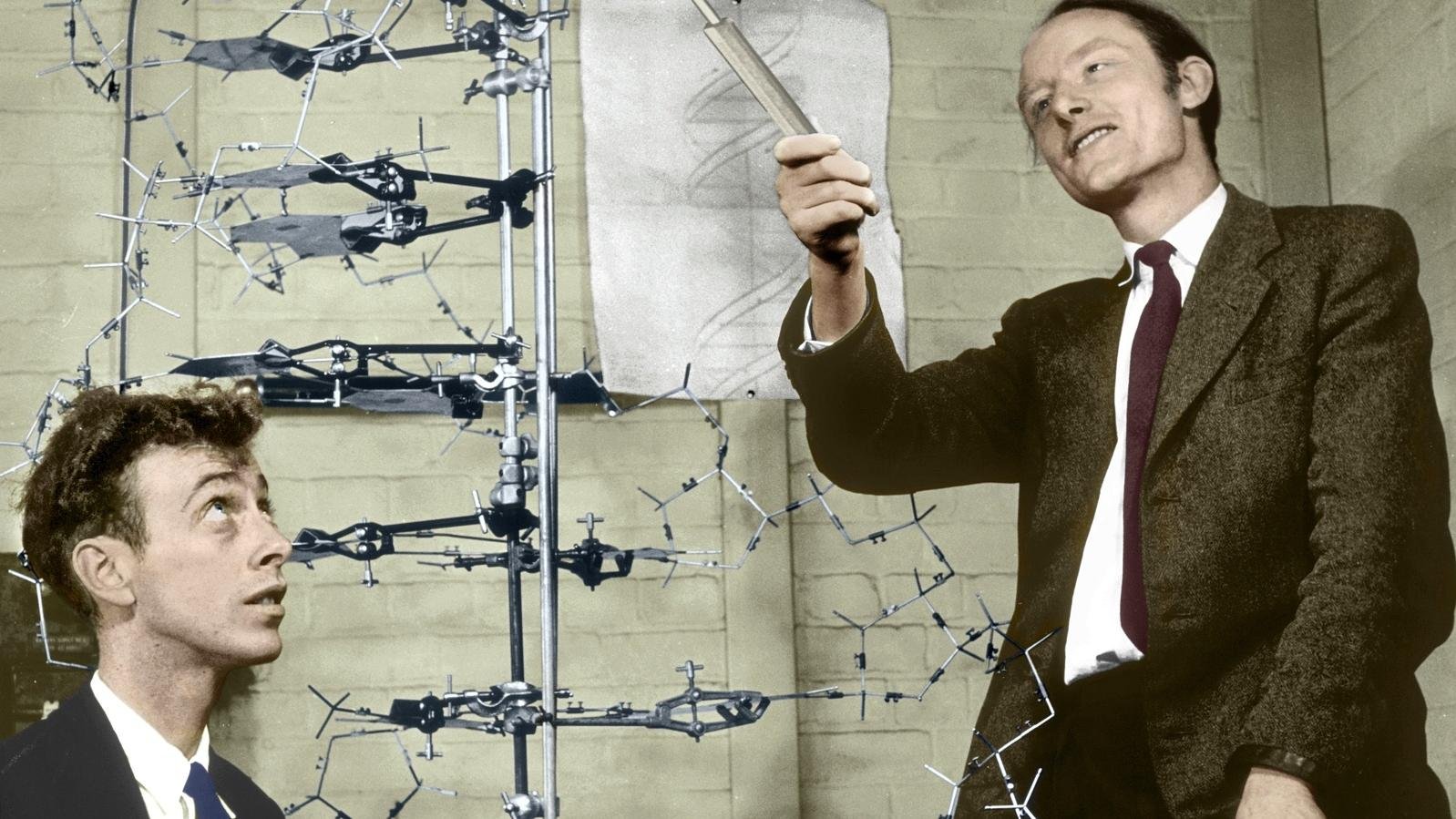

Other times, it’s by design. No need to list them. There are endless examples and they go from the telephone (Graham Bell) to the DNA structure (Rosalind Franklin, James Watson and Francis Crick).

My question is about sui generis, seminal, unprecedented CONCEPTS.

Are we, as human beings, even capable of ideating them?

Are we able to think of the unthinkable?

Part of me tends to think that if we’re capable of conceiving of the ideas behind expressions and adjectives like “sui generis”, “seminal” and “unprecedented”, then that probably means we’re also able to conceive of things that match these ideas.

Then again, the other part immediately goes:

“Oh yeah? Ok.

Think of something unthinkable, then.

Go ahead.

You can’t, right?

And if you can, then… it ain’t unthinkable.”

The reason I started reflecting on it is because it seems like EVERYTHING that we, as thinking beings, are able to ideate or conceptualize already exists and is, somehow, ALREADY THERE. It’s… for lack of a better word, a GIVEN. Floating in the ether, as part of our existence, somewhat ruling and/or influencing our lives. Sometimes, we don’t even see these things; but we do feel them. And, apparently, that’s evidence enough for us to be able to conceptualize them.

Take TIME, for example.

Time, as a concept, is self-evident. As a matter of fact, I sometimes wonder who the heck was the first person to feel the indefinite and continued progress of existence, identify it as “something” and then, decided to call it “time”.

I feel like “time” may be considered an utterly original concept, in the sense that, as far as my super limited understanding goes:

It wasn’t inspired by any previous reference.

Actually, it’s quite the contrary: time is the reference behind concepts such as the theory of relativity, birthdays, etc.It is not a combination of other existing things.

Years, months, days, hours and seconds were invented by us – arguably by the Egyptians and ancient Babylons – as a way to make sense of the concept of time, and not the other way around.It is not an evolution of something else.

I can’t even conceive of what could possibly have been there before time itself and that would eventually evolve into time.

Now, the three questions I often ask myself:

Did human beings invent time? Nope.

Did human beings discover time? Maybe.

Did human beings turn time into a concept? Yep.

Let’s take a look at another example: POWER.

“Power” is another concept that, at least in my eyes, is utterly original in the sense that:

It wasn’t inspired by any previous reference.

It seems to be the contrary: from the oldest cave paintings ever found, with people hunting animals, to the latest battles fought at The International Dota 2 Championships, power seems to be THE ultimate inspiring reference.It’s not a combination of other existing things.

Some may argue that if we combine things like money, sex and influence, the end result is power. I beg to differ. To me, money is a FORM of power. So is sex. And definitely influence.It’s not an evolution of something else.

In fact, it’s such a seminal concept that entire fields evolved FROM it and revolve around it: politics, law, religion, sports, business, etc.

Obviously, those same three questions pop up in my hed again:

Did human beings invent power? Nope. (The fights for mating rights in the animal kingdom are the ultimate proof of that).

Did human beings discover power? Maybe.

Did human beings turn power into a concept? Yep.

In both cases, the answer to the first question is pretty clear and straightforward in my mind.

No, we didn’t invent “time’.

And no, we didn’t invent “power”.

As I write this, the answer to the second question still remains a bit blurry to me. I still didn’t fully make up my mind about it. Mostly because I struggle with the verb “discover”. I’m not sure if we discovered time and power (regardless if by accident or by design).

I feel more inclined to say that throughout our entire existence as human beings, we have always intuitively felt the passing of “something” (in the case of time), and empirically felt the allure of “something” else (in the case of power).

Furthermore, we could sense that those “things”, no matter how intangible, had a very real and tangible effect on our lives. And even if we could – perhaps – “explain” what the first something and the second something were, we probably didn’t know what to call them. Until one day, one of us finally succeeded at putting his/her finger on what those “things” were and found a way to “label” them. Decided to give them a “name”.

And just like that, we started calling the first something “time”, and the second something “power”.

Now, does that mean that we discovered them?

Like I said… maybe.

Why “maybe”?

Because discovering something means uncovering something that was previously covered. It means bringing this something to light. Ultimately, discovering something means BECOMING AWARE of its existence. And for some reason, I believe that we’ve always been somewhat aware of the existence of “time” and “power”.

Some way, somehow, we knew those “things” were there.

Discovering Something Implies Being Unaware of the Existence of This Something

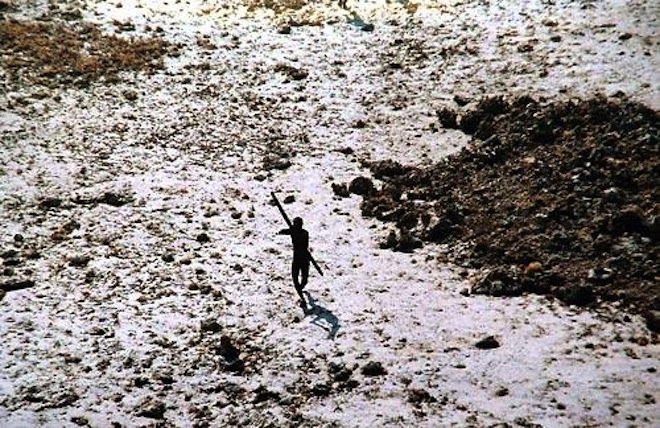

To me, discovering something would be, for example, bringing the lifestyle of the Northern Sentinelese tribe to light.

Completely isolated from the rest of the world, and protected by the Indian Government, this tiny piece of land located in the Bay of Bengal is part of the Andaman Islands and is one of the most mysterious places on the planet, as no one knows what happens in the depths of the thick forest that covers the Island of North Sentinel.

How do they live? What language do they speak? How many of them are there? Do they know how to make fire? What do their “houses” look like? And – this is truly mind-blowing – how on Earth did they manage to survive the 2004 tsunami that killed over 200.000 people? Is it possible that they owe their survival to some kind of groundbreaking technology that we, in the so-called “civilized” world, are still completely unaware of?

No one knows.

I mean… how crazy is that? In a world where human beings have already succeeded at both going to the ultimate heights of Space and reaching the bottom of the deepest place on Earth (the Mariana Trench), to this day, everything we claim to know about North Sentinel is nothing but a wild guess. And you know what? I hope it remains this way forever, for the sake of the Sentinelese people. ;o)

Now, let’s say that someday, all those mysteries are revealed and all those questions are answered. And just like that, we discover that the Northern Sentinelese don’t communicate through sound, but through sight.

Sounds implausible, I know, but not impossible.

Especially when we consider the fact that their Andaman Sea “relatives”, the Moken people (specifically Moken children), have the unique ability to make their pupils smaller and change the lens shape of their eyes, which allows them to see as well underwater as they do above it. So, maybe, people from the Andaman region carry some sort of mutation and are genetically wired to be able to control their eye functions at will.

You know how we widen our eyes when we’re scared and how we narrow them in disgust? We’re essentially communicating with our eyes. In this case, we’re communicating two very specific emotions. Now, use the same rationale and imagine a hypothetical situation where someone (for example, the Sentinelese people) is able to communicate EVERYTHING using only their eyes, and everything they encompass: color, iris, pupil, lens, etc.

Imagine that to be true for a second.

Something we didn’t even know existed – communication solely through sight – would now suddenly be added to our “human experience” repertoire, as we were made aware of the fact that human beings can – indeed – “talk to each other” through sight.

Now THAT would be quite a discovery.

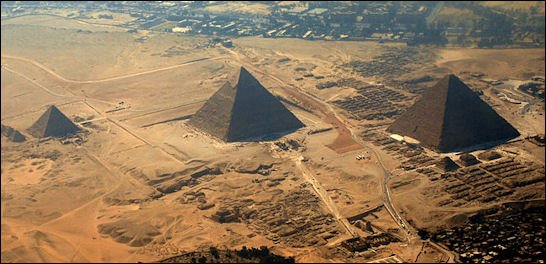

It’s the same thing with the Pyramids.

How were they built? Somehow, no one has managed to reach a definitive answer yet. We’ve come as far as sending probes to freaking Mars, but we still can't crack that one. Unbelievably enough we still don’t know how one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World came to be. Most people hypothesize about some crazy, ancient, unknown engineering solution.

But maybe it isn’t that. Maybe the secret lies in the stones. Literally. Have you ever thought about that? Maybe the Egyptians were aware of some crazy chemical formula that allowed them to temporarily turn stones into something much much lighter, say, a “sponge” of some sort, which would later revert back into stones.

You know how we can get blocks of ice and, depending on the conditions we manipulate them in, we can turn these solid blocks of ice into gas? And then, afterwards, depending on how we handle this gas, and depending on certain conditions, we can solidify them back again? Maybe the Egyptians knew how to do the same thing with stones. Maybe they knew how to turn them into something else, something much lighter. Who knows? Again, we can only guess.

For now, this all sounds like I’m talking crazy.

But how cool would it be if, maybe one day, a team of archeologists came across an old manuscript hidden way deep in the sands of Egypt? And we realized that there’s a mathematical equation written on it, teaching us how to turn hard minerals into soft sponges, much in the same way we’re able to turn heavy blocks of ice into “weightless” gas.

Imagine that to be true for a second.

Something we didn’t even know existed – a formula that could turn stones into sponges – would now suddenly be added to our “human experience” repertoire, as we were made aware of the fact that human beings can “turn solid, heavy minerals into airy, light sponges”.

Now THAT would be quite a discovery.

That’s why I say maaaaybe we have discovered “time” and “power”.

Because I believe we’ve always been aware of the existence of “time” and “power” (even if only intuitively and/or empirically).

And discovery implies being UNAWARE of the existence of something.

Oh, and just to be clear, my train of thought is starting from the premise that the acts of “DISCOVERING something” and “FINDING something” are two completely different things, since the second one (in my eyes) implies being previously AWARE (even if through vague rumors) of the existence of something.

“Concepts are the human mind’s way of simplifying the world around.”

So, if we didn’t invent “time” and “power” and if we didn’t discover them either, how did these things become… well, “things”? And how is it possible that we can think about these “things”, about time and power, and talk about them, and understand them much in the same way we think about, talk about and understand things like “trees”, “pyramids”, “islands” and “horses”?

Simple. We conceptualized them.

And as we’ve established, they can be considered utterly original concepts.

But as we’ve also established, “time” and “power” DO exist.

Not only that: we’re aware of their existence.

Which brings me to two other questions that have been keeping me awake:

“When it comes to utterly original concepts, are we only capable of conceiving of those that already do exist?”

And “must we be aware of the existence of these utterly original concepts,, in some way, shape or form, in order to be able to conceive of them”?

What do you guys think?

Let’s say the answer to both questions above is YES.

If that’s true, that we’re only capable of conceiving (again, I’m talking EXCLUSIVELY about utterly original concepts) of things that do exist; and whose existence we’re aware of, then maybe the following conclusion is (once again: MAYBE) also true: “if we can conceive of it, then it MUST exist”.

Now, let’s say the answer to both questions above is NO.

Well, in that case, then Lavoisier’s conclusion in his 1789 masterpiece “Elementary Treatise on Chemistry” is probably not entirely correct (I’m being diplomatic here, and purposefully avoiding the word “wrong”… ;o)). This is what he said on chapter XIII:

“(…) Nothing is created either in the operations of art, or in those of nature, (…) and that what happens is only changes, modifications.”

In other words, Lavoisier is saying that we can’t – and don’t – CREATE anything; at least, not from scratch. We can use what already exists as building blocks to “create” something new (like getting the utterly original concept of a “woman”, the utterly original concept of a “fish”, and create the concept of a mermaid). But we can’t create new building blocks. And you know what? Personally, I often ask myself if we’re even able to CONCEIVE of brand new building blocks that don’t exist, let alone, create them.

I don’t really like the idea that human beings aren’t able to conceive of brand new, seminal, first-of its-kind, unprecedented hmm…let’s call them “conceptual building blocks”. Because if that’s true, then that means that all existing building blocks already exist as a GIVEN. And all that’s left for us to to play combinatorial analysis. My creative self has the hardest time accepting that.

I don’t care if the number of possible combinations is higher than mol (I’m talking about that ridiculously high number from our chemistry classes: 6,02 x 10 raised to the power of 23). I don’t even care if this number is higher than the factorial of a mol (although, I must admit, that’s a helluva huge number…;o)).

In all honesty, even if the number of combinations we can come up with proves to be infinite, the idea that all we’re ever going to be able to do is “play with a given set of Lego bricks”, instead of conceiving of, inventing and then adding new and never-before-seen bricks to this Lego set doesn’t sit well with me, for some reason.

But what do I know, right? I’m the first to admit that my knowledge of concepts and things pertaining the realm of ideas is as small and limited as anyone else’s.

Which is why the most reasonable thing to do is going to the masters.

Please, give it up for the undefeated champions of concepts and ideas!

On the left corner, straight from the highlands of the UK, we have him, the one, the only, David Hume, a.k.a “The Empiricist”.

On the right corner, him: the Greek Freak, “The Caveman”, author of the most famous “Theater of Shadows” of the Western Civilization… PLAAAAAAATO.

Who will take home the belt?

And who’s going to be the loser?

Well, no need to watch this fight guys.

Clearly, I’m the loser, as both of them believe in the premise that life is made of a given number of “conceptual building blocks”.

Plato calls these blocks FORMS (to which we have access thanks to a quick visit we paid to the “world of ideas” before we were even born).

Hume, in turn, calls them IMPRESSIONS (to which we have access solely through experience).

Nevertheless, what matters is that they – the undisputed, undeniable masters –, together with Lavoisier, seem to agree on the fact that we, as human beings, CANNOT originate these conceptual building blocks at will, deliberately.

Were it to be true, that’d be incredibly sad.

Not to mention, a monumental defeat to all of those who seek originality, feed on creativity and are conceptual thinkers at heart.

Think about it for a second: realizing that every single piece of creative work and artistic expression will always be derivative of something else… isn’t that kind of a bummer? I mean, on the most fundamental, conceptual level.

Of course, we can appreciate the artist’s technique; we can be inspired by the work of art in front of us and be moved to our core. But strictly on a conceptual level, there’s always going to be part of us that will go: “mmm, I think I’ve seen this before somewhere” or “this sounds familiar”.

Do you know when I get this feeling?

Every single time I watch a sci-fi film.

(Not So) Alien Concepts

Think of any sci-fci movie you’ve ever watched.

Think of the creatures in these movies. Alien beings. We’re talking creatures from different worlds and dimensions here. Don’t they all look a bit too familiar?

From the classics such as Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien to the more recent ones, such as Dennis Villeneuve’s 2016 The Arrival.

From the strange beings born in the mind of Mexican director Guillermo Del Toro (2004 Hellboy, 2009 Pan’s Labyrinth, and 2013 Pacific Rim) to the ones conceived in the mind of South African director Neil Blomkamp (2009 District 9).

From the gooey disgusting creatures in the hilariously fun B movie Tremors (1990) to the cute and sweet protagonist of Steven Spielberg’s 1982 ET – The Extraterrestrial.

In some way, shape or form, it’s almost as if we could RECOGNIZE something in them, which means, it seems like we’ve seen them before. For starters, most of them have “heads” and “limbs”. Also, most of them have the shape of a human being, as they walk on two legs, usually have two arms and are (at least on the outside) bilaterally symmetrical.

And even when they don’t share similarities with human beings, they do so with animals we all know of or have seen before.

Some look like giant prawns (District 9).

Others look like giant squids (The Arrival).

And then, there are those who look like giant worms (Tremors).

See? The fact that I can throw the “ideas” of prawns, squids and worms are proof that, conceptually, the design of these creatures is NOT utterly original.

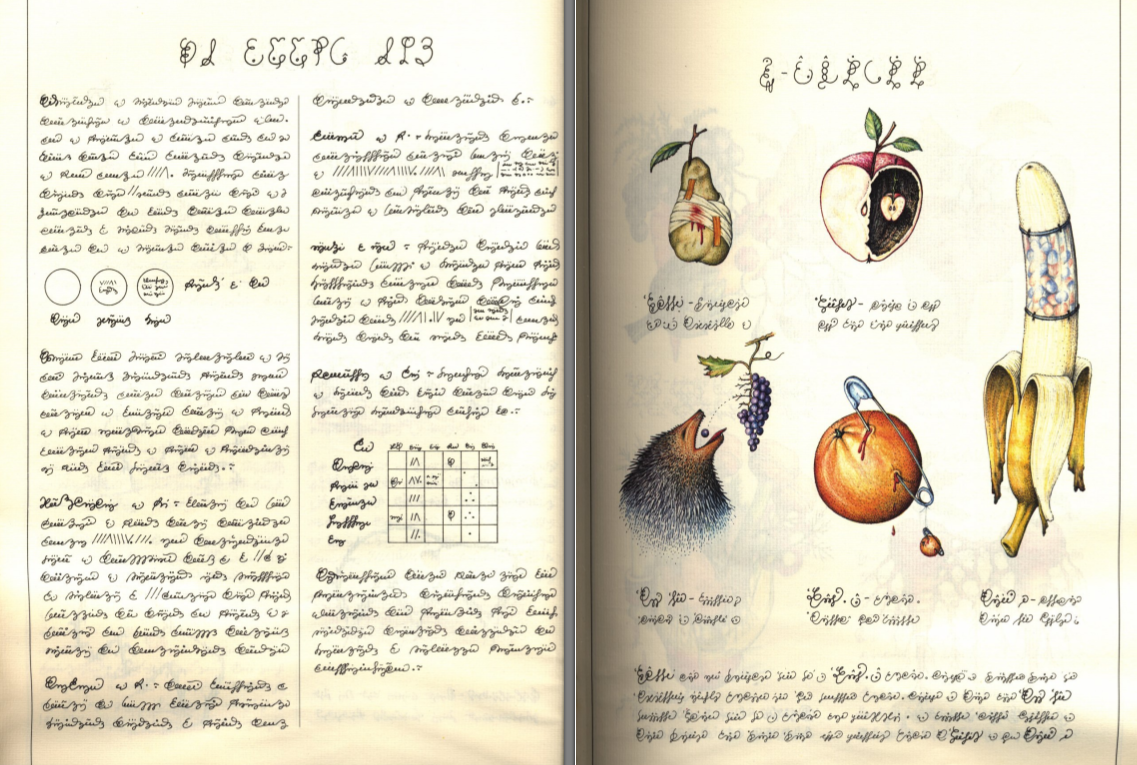

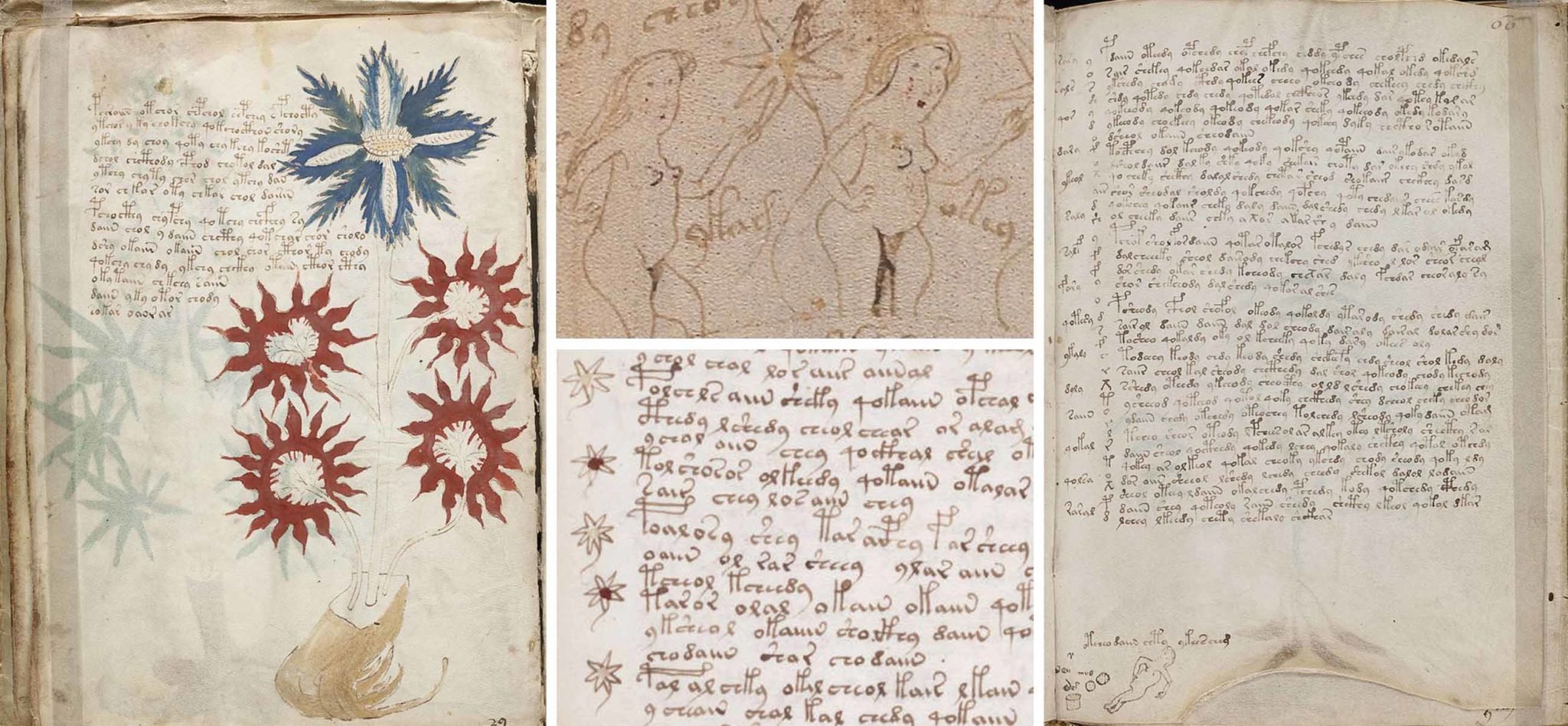

Have you guys ever heard of a book known as “The Strangest Book Ever””?

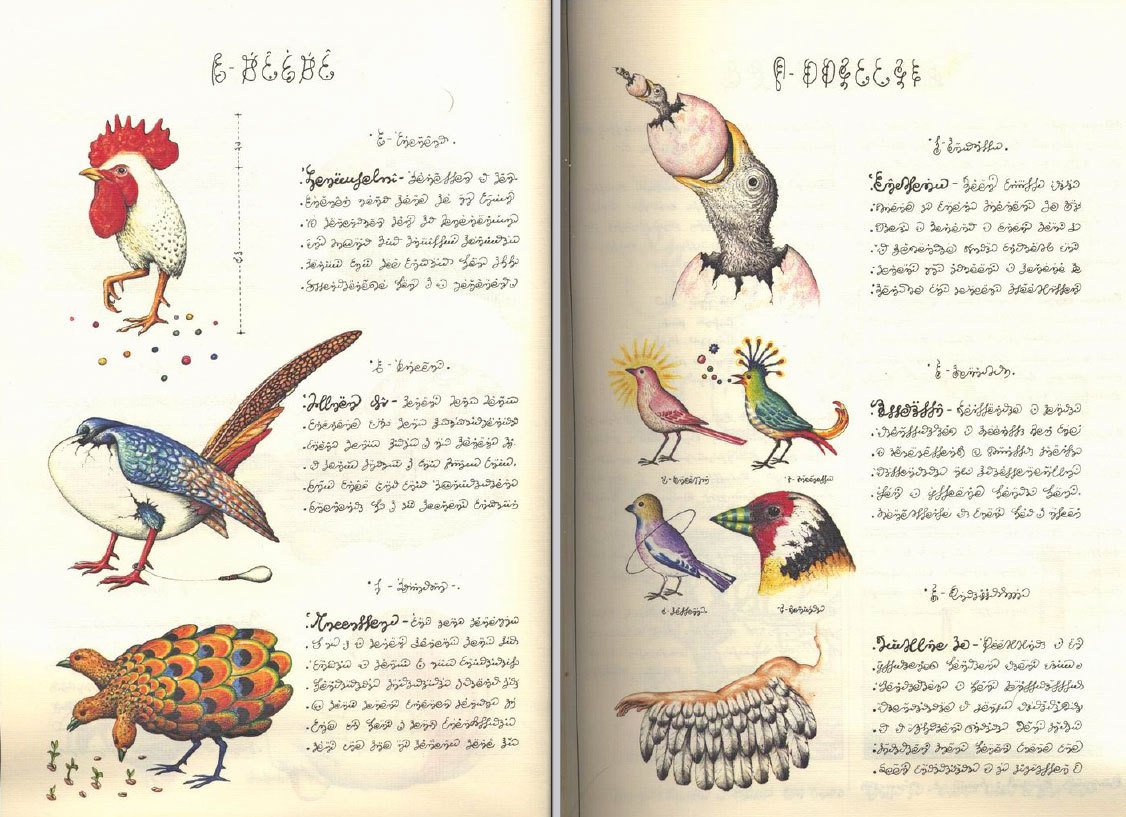

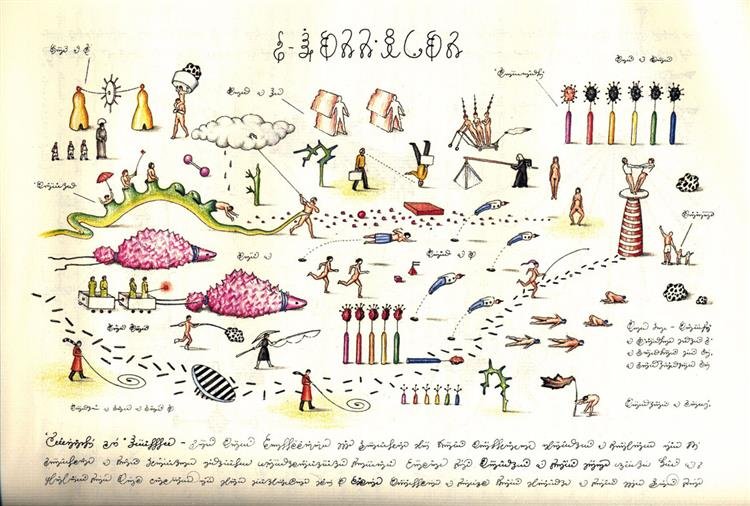

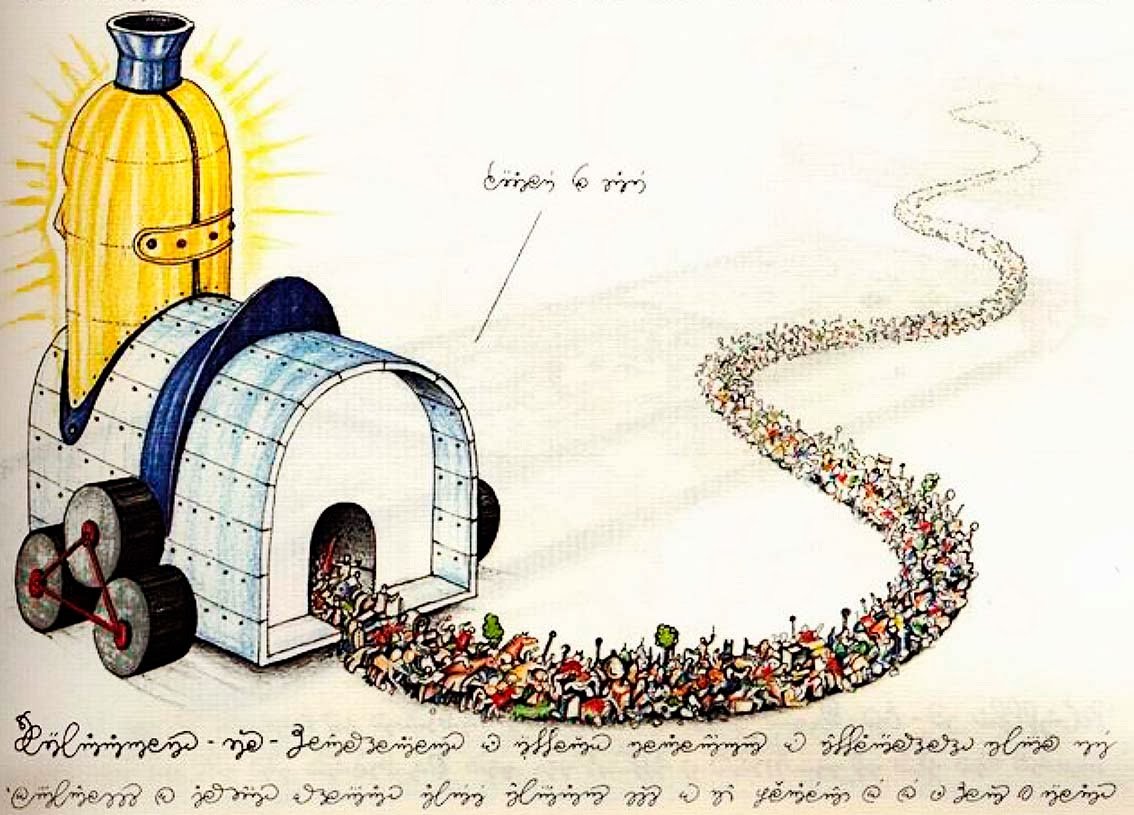

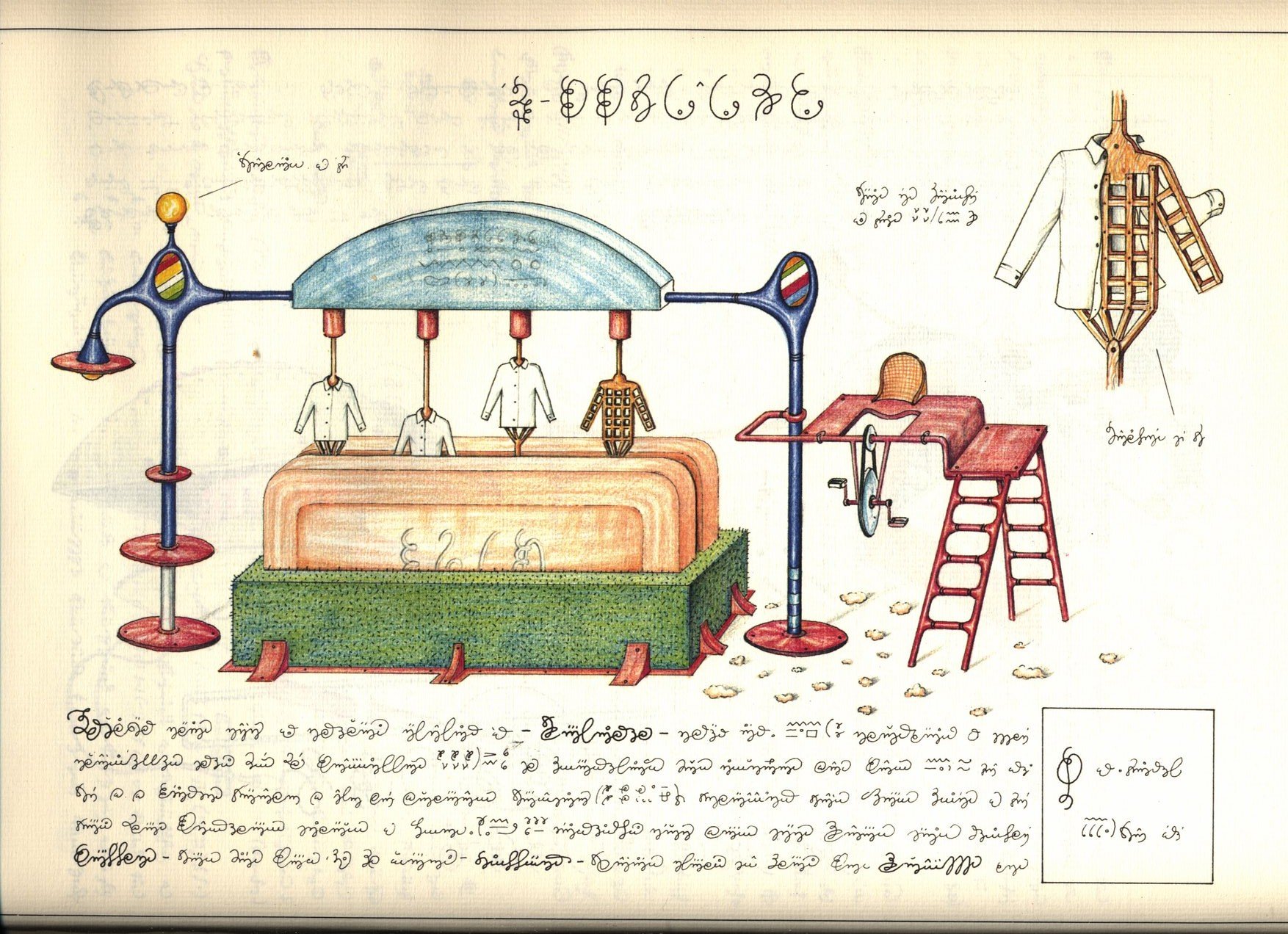

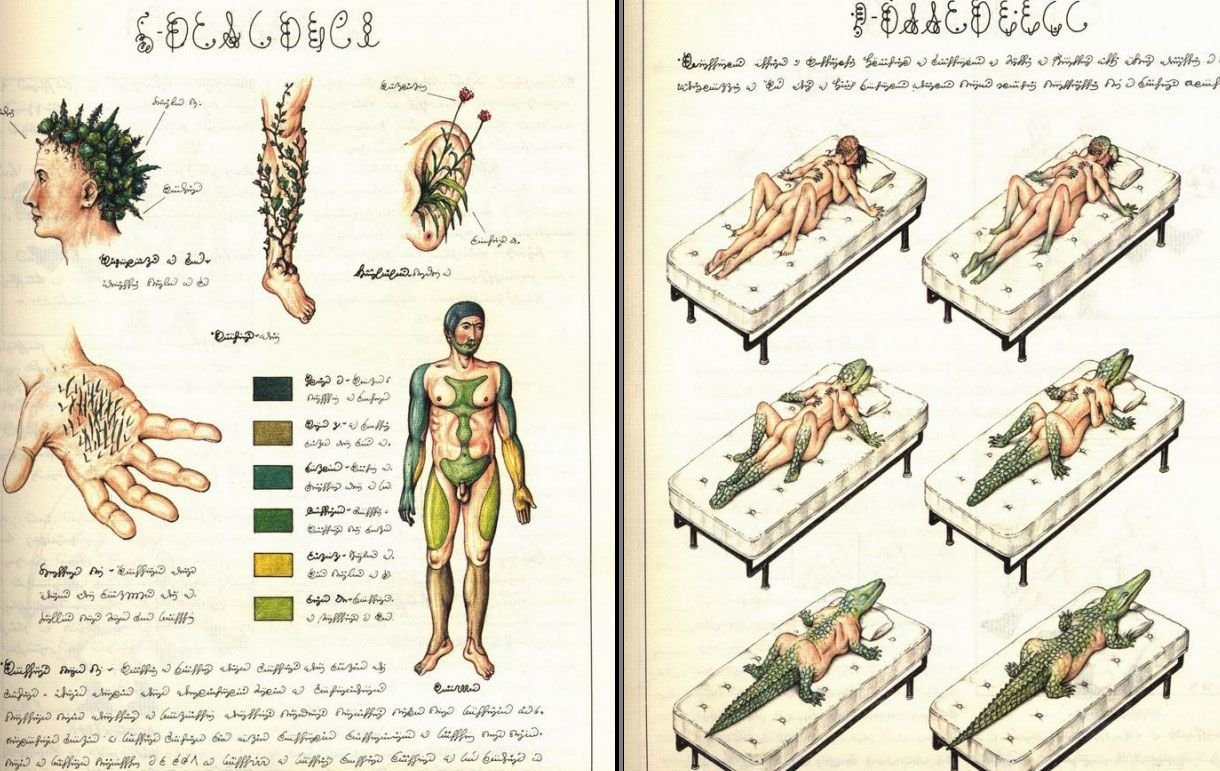

It’s called “Codex Seraphinianus”. It’s kind of an encyclopedia describing and depicting the living beings of an imaginary, unknown world. The book was created and illustrated by Italian architect and artist Luigi Serafini, between 1976 and 1978.

I’m not going to lie: for a book that holds the title of Strangest Book Ever, I was kind of well… disappointed. Yes, it is original. And yes, it’s beautifully, exquisitely illustrated. But from a conceptual standpoint, I felt like every page presents us with nothing more than a series of drawings that are, more or less, representations of what David Hume calls COMPLEX IDEAS.

In other words, Serafini took a bunch of “simple ideas” (as Hume calls it) and combined them together, in unexpected, weird, odd ways. That’s it.

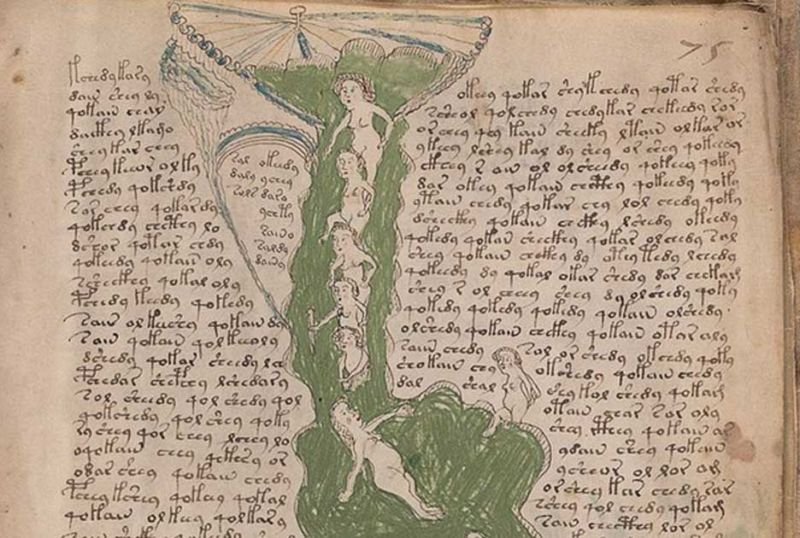

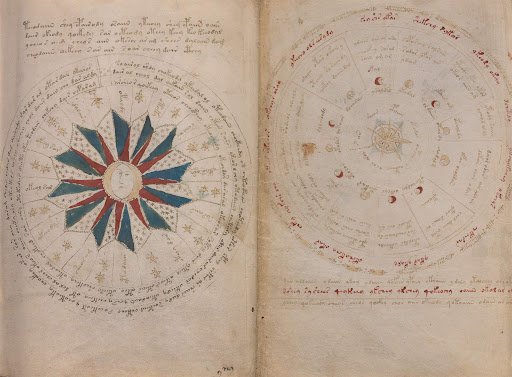

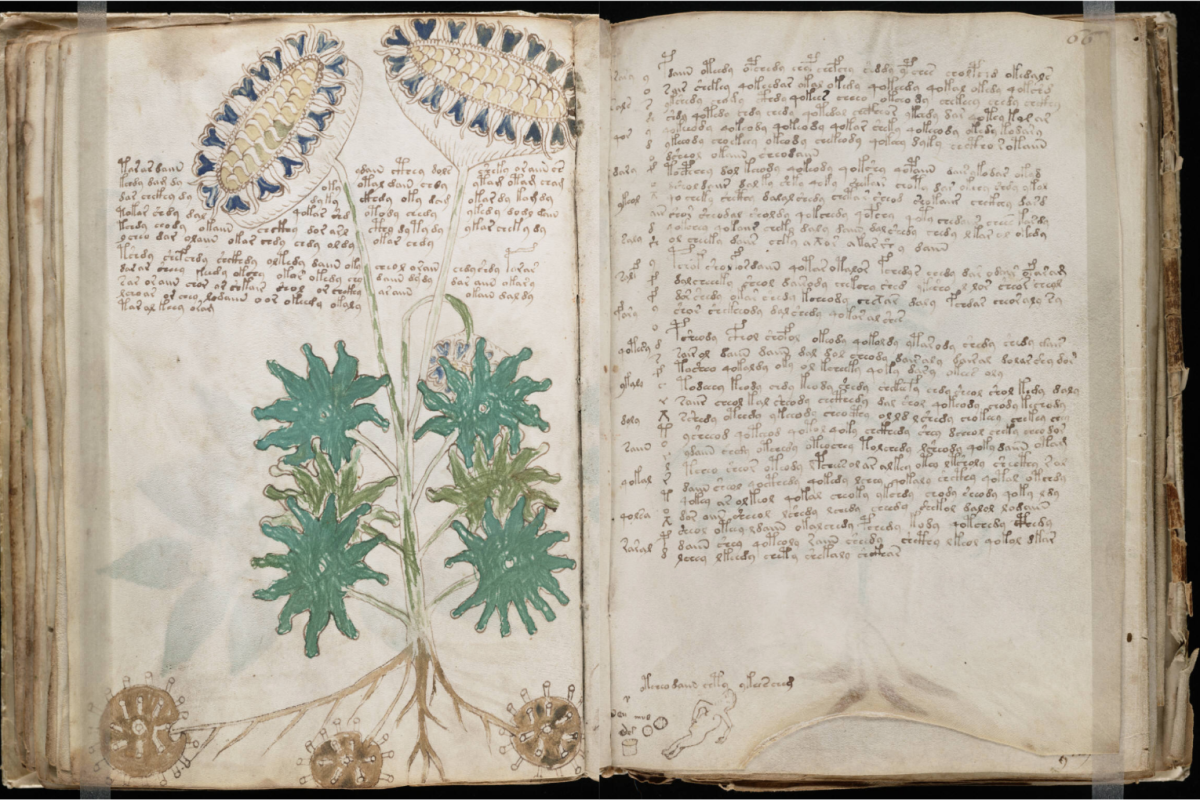

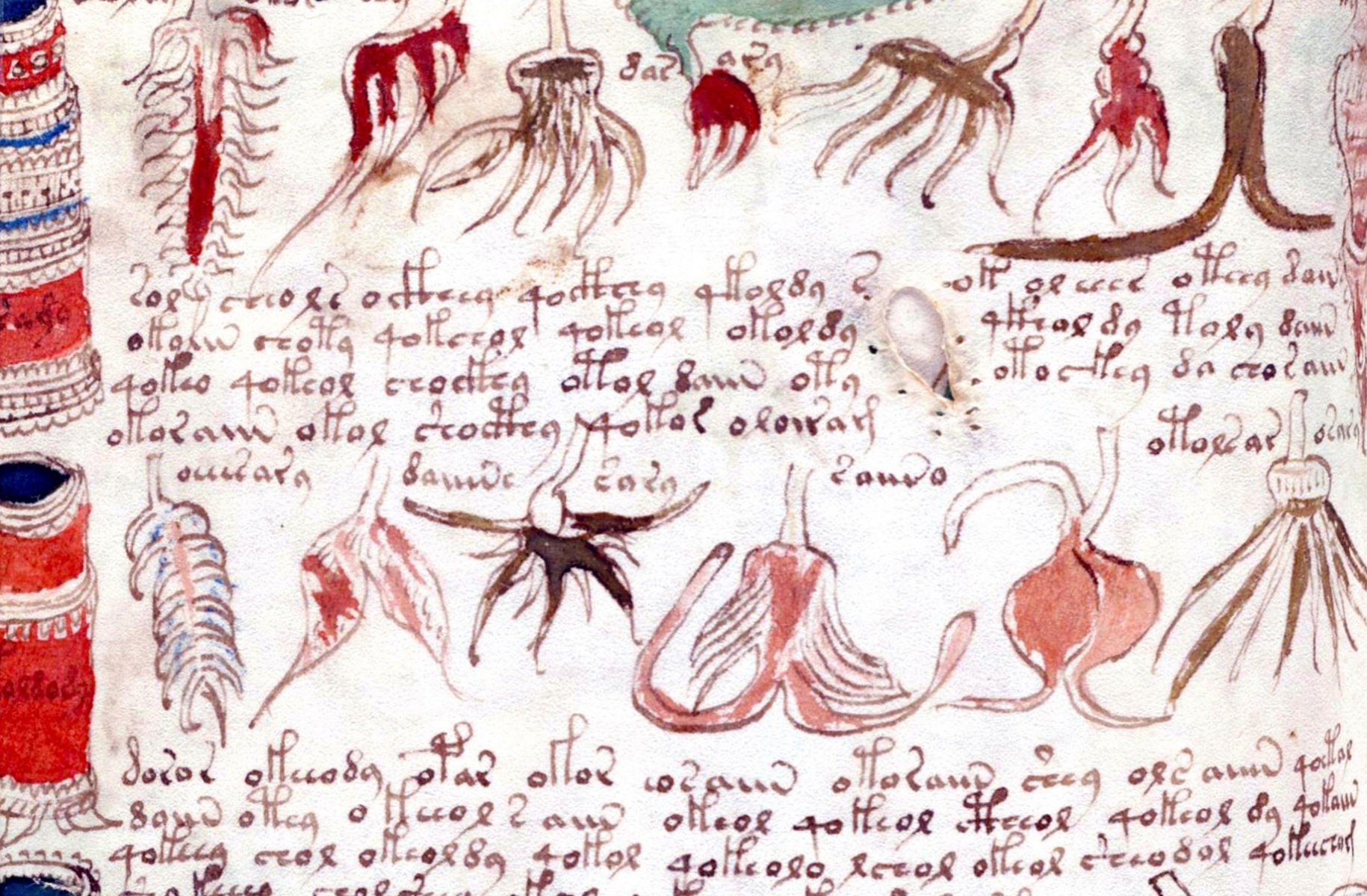

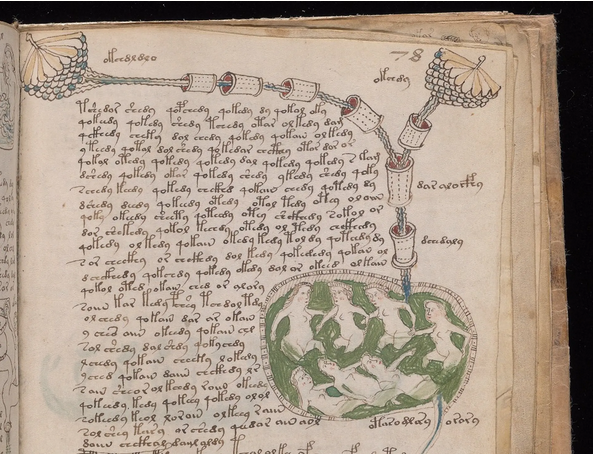

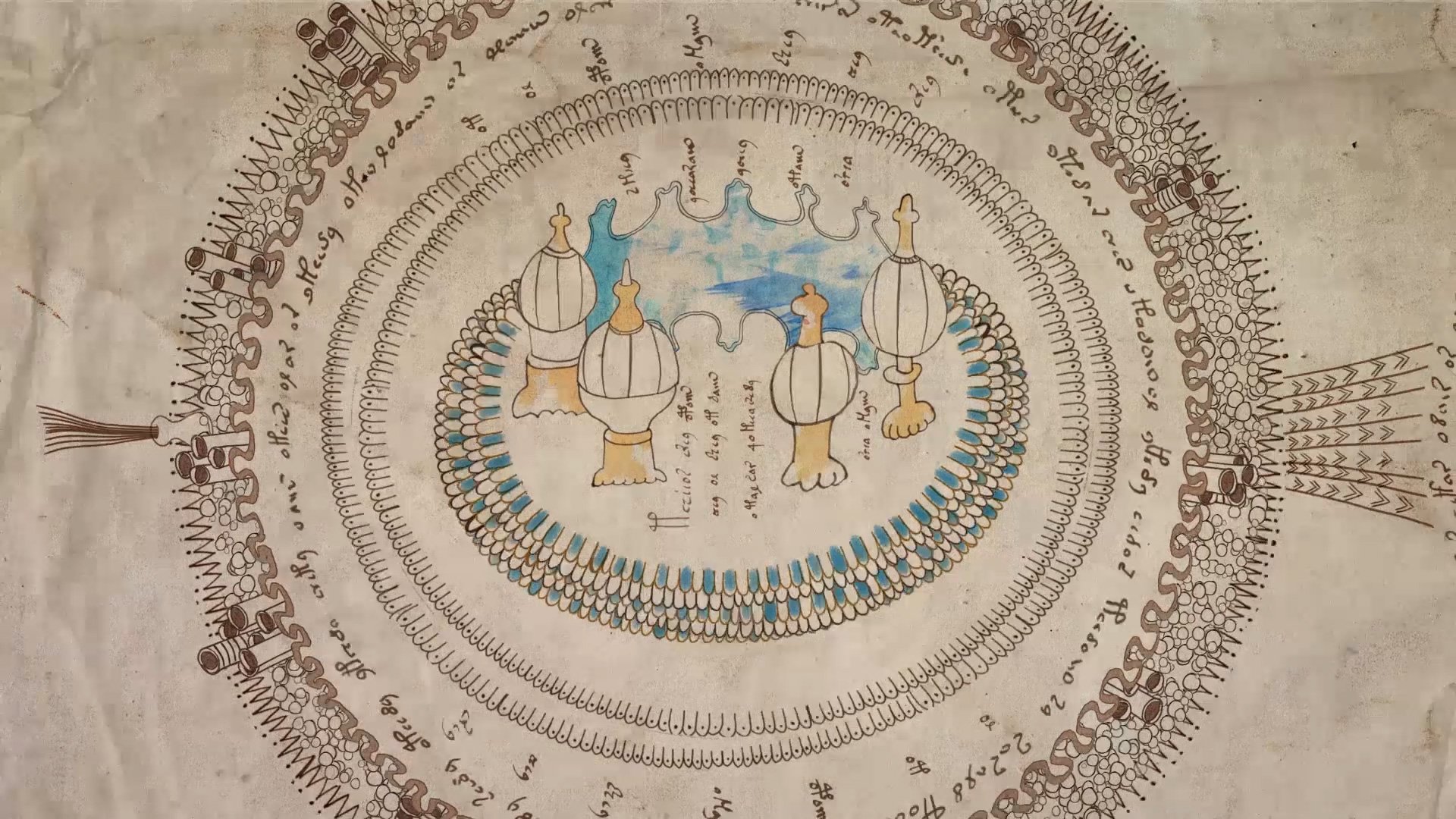

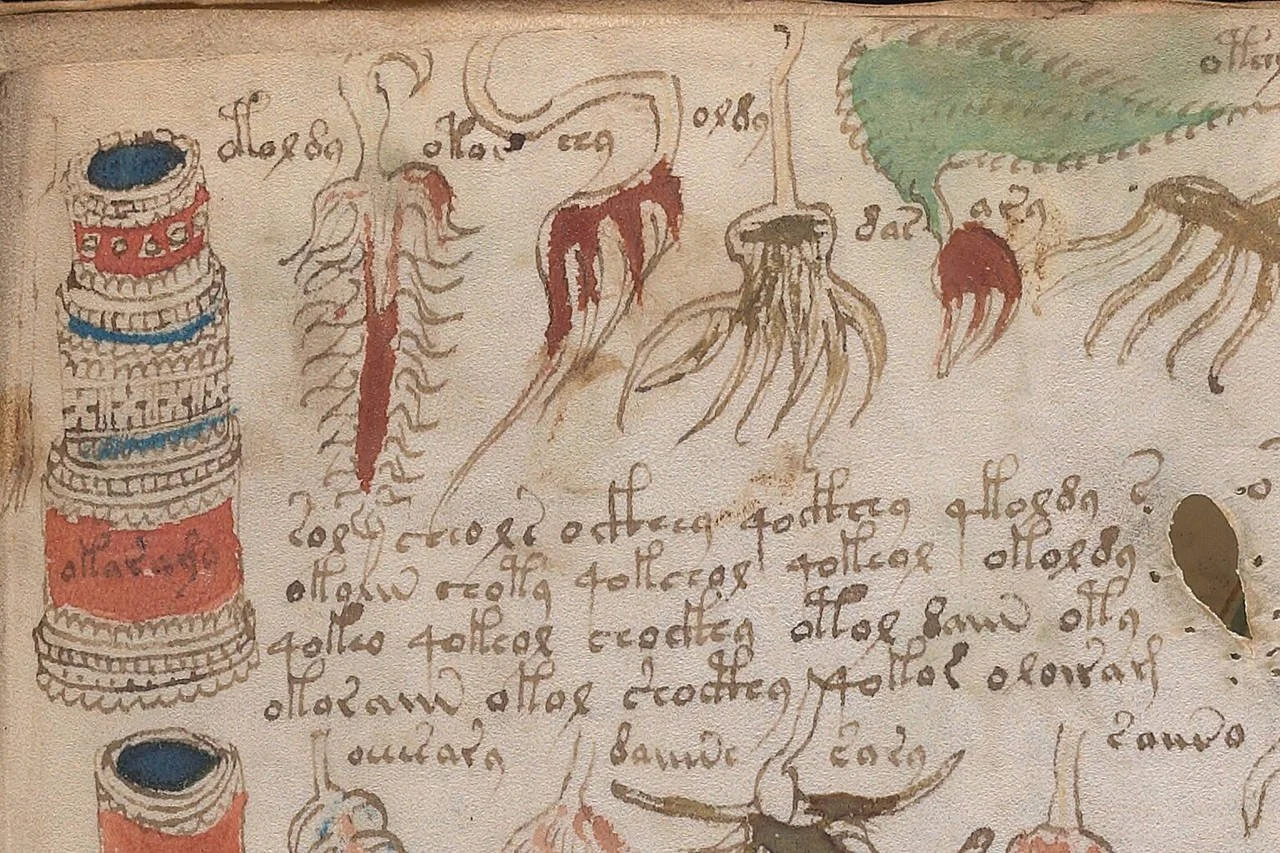

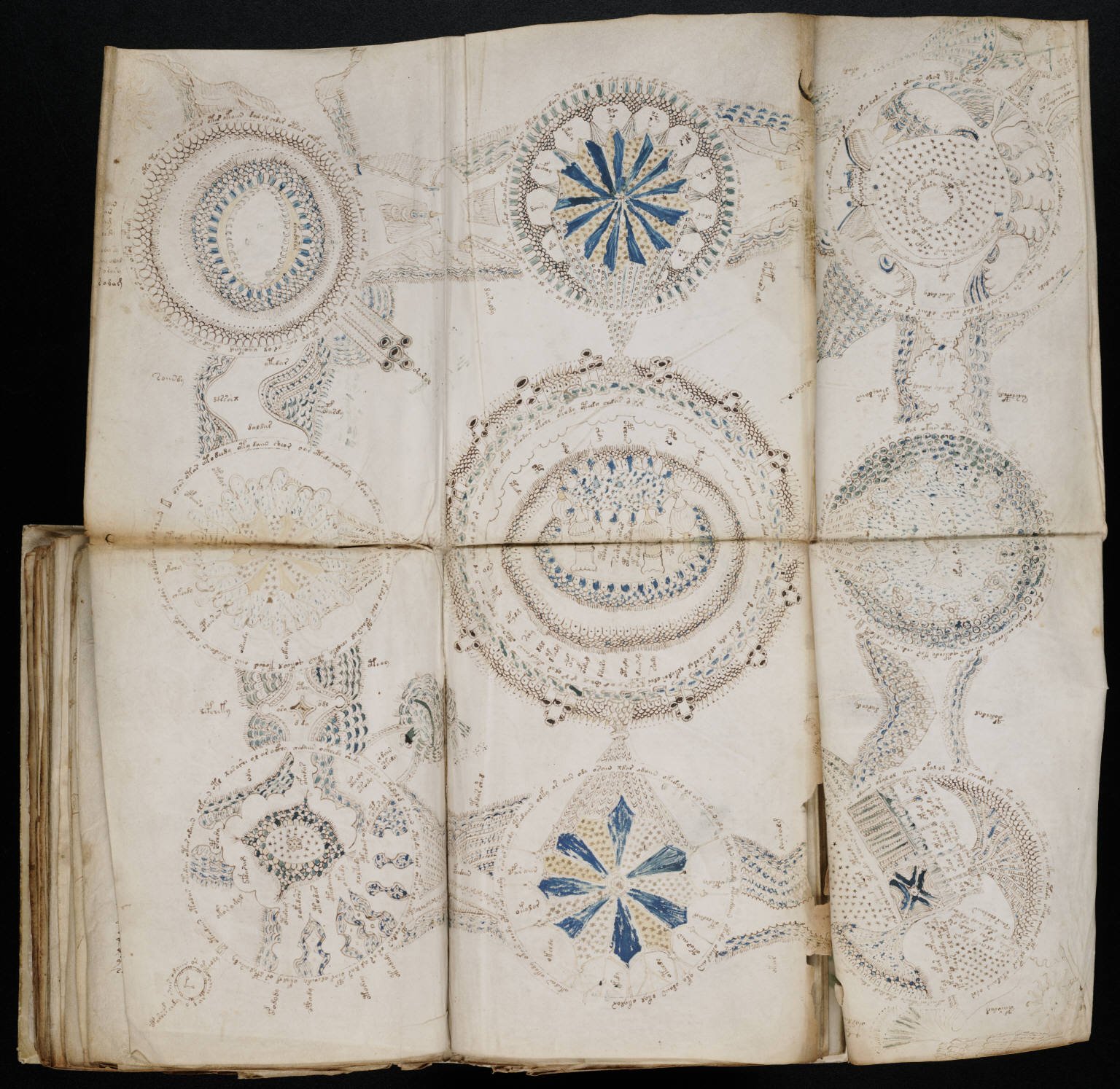

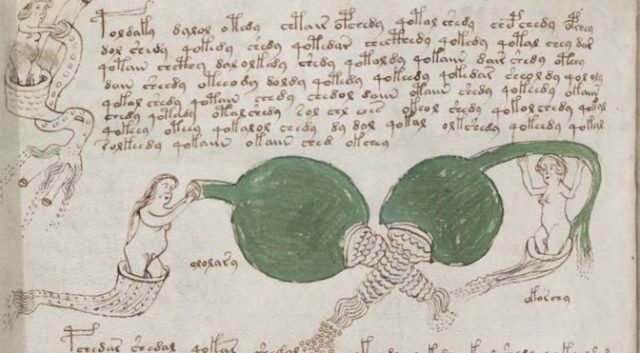

Speaking of Codex, there’s another book, commonly referred to as “The Most Mysterious Codex” in the world, called the Voynich Manuscript.

Scholars believe it was written in the 15th century (its authorship remains unknown to this day), and it contains roughly 234 pages touching on subjects that go from botany to astronomy and everything else pertaining the natural world. Which means, in short, that it talks about things that already exist in Nature, as we know it (or knew it, some 600 years ago).

Conceptually speaking, as far conceptual building blocks go, as far as forms (in Platos’s vernacular) and impressions (in Hume’s glossary) go, there’s nothing utterly original in neither one of those books. Nothing really new was deliberately conceived. Not in the Strangest Book in The World and not in The Most Mysterious Codex in The World.

Bummer.

Conceptual Lego Bricks

I remember one day, way back when I was still a teenager, I asked a friend of mine who could play the guitar “how many notes and chords were there and if all the notes and chords have already been invented”.

At the time, I was thinking about taking guitar lessons and I was basically doing some calculations in my head, wondering how long it would take for me to learn how to play every single note and chord. Unbeknownst to me at the time, on a deeper level, though, what I was actually wondering was if the amount of notes and chords one could play was LIMITED.

For some reason, something in me wanted (or better yet, NEEDED) to know if it was possible for someone to conceive of a note or chord that’s never been heard, played or conceived of before. I don’t know why I was so moved or intrigued by this question, but I do remember my friend’s answer: “yes, all the notes and chords in existence have already been invented”.

Basically, he was saying that – on a conceptual, fundamental level – we had already reached the end of the musical combinatorial analysis. Right there and then, any desire I might have had to play the guitar disappeared. It’s like, all of a sudden, there was no excitement left. I lost all the interest I had in learning to play the guitar. Pretty strange, right?

Anyway, as a consolation prize to all of us, creatives in our endless quest for utter originality, at least, it seems like the number of combinations humans beings are able to create with the limited amount of notes and chords in existence IS limitless. As a music fan, a rock and roll aficionado and a hip-hop enthusiast, I thank God everyday for that. ;o)

The more I think about:

“our amazing ability to come up with a seemingly infinite number of original creations with a given set of conceptual Lego bricks”

vs.

“our complete inability to conceive of (let alone create) even ONE single new conceptual Lego brick”,

the more challenged I feel to prove the latter wrong.

And the more defeated I feel time and time again, after every single fail.

It’s incredibly easy for me to drift into my own reveries, where I ask myself questions like:

“Who said that life on other planets is or should be like life as we know it on Earth? Maybe we’ve found life elsewhere already, it just wasn’t what we expected it to be and/or didn’t meet the criteria we – somewhat arrogantly – established. Perhaps life outside of Earth exists in ways we can’t fathom yet.”

“Why does every alien creature in sci-fi movies seem to have a sort of “body”? Or why are they always depicted as some kind of “organism”, even when they’re presented as an alien virus? Maybe we shouldn’t be thinking in terms of an “organism”. Maybe alien creatures are something completely different.”

“Does every chemical compound need to be categorized as organic or inorganic? Can’t there be third option, completely different from these two?”

“Instead of thinking if there could be another state of matter (liquid, gas, solid and plasma), why can’t we conceive of “something else” happening to water, for example? Let’s forget about switching states of matter for a second. As a matter of fact, let’s forget about “state of matter” altogether. Can’t we conceive of something else OTHER than what we came to know as “state of matter”?

These questions fascinate me in ways I can’t even begin to explain. It’s super fun to think about them. It’s exciting to entertain them. But every single time, not even a second after one of these questions takes over my mind, another one (and it’s always the same one), pops in my head.

“Suuure, of course. Like what?”

And that one – THAT ONE –, frustrates the heck out of me, simply because to this day, I can’t seem to find an answer to it. Essentially, to answer any of these questions, I would need to first conceive of a brand new “conceptual building block”, an utterly original “conceptual Lego brick”. And unfortunately, I can’t. God knows I tried and keep trying. But for the life of me, I can’t.

So maybe the masters are right.

Maybe all that’s left for us is “play Lego”.

Maybe, as human beings, we’re not meant to be able to conceive of new forms (in Plato’s lingo).

Maybe we have no business trying to conceive of new impressions (in Hume’s lingo).

But we DO have one card left: we can assign new MEANINGS to any given concept.

The “form of a tree” is a given?

So what?

That doesn’t mean I am obligated to always see a tree, as in the plant. I can look at a tree and see “my family’s genealogy” if I want to. I can think of a tree and see a bunch of “Christmas presents”. I can see the “the place where kids will be playing on a swing”. The tree can mean a bunch of different things to me.

The “impression of red” is a given?

So what?

That doesn’t mean I am obligated to always see red, as in the color. Red can mean so much more. It can mean passion. It can mean rage. It can mean being high. It can mean being in love. It can mean “Ferrari”. It can mean life, as in blood. It’s really up to us to assign new meanings to the impressions of red.

When I think about that, suddenly, my urge to conceive of new conceptual Lego bricks is (a little bit… ;o)) soothed.

After all, if I can’t come up with utterly original concepts, unless:

they already exist and

I’m aware of their existence

(and even when both criteria check out, I’m still not sure if I can do it wilfully and deliberately),

well, then at least, I can maybe go for the next best thing.

I can simply reinterpret the ones that already exist.

Assign new meanings to them.

And in doing so, I can hopefully, even if only on the most superficial of levels and in the slightest of ways – reconceptualize – them, if you will.

When you start looking at things from this angle, possibilities truly ARE endless.

So, let’s try a little game here, shall we?

Remember the examples we drew from, in the beginning of this article? How “Time” and “Power” could be considered utterly original concepts?

Let’s see if we can assign new meanings to them.

We all know of that “time is money” saying, right? The Zeitgeist we live in has taught us all that time means money. But what if it meant something else? Instead of “time is money”, what if we reinterpreted the concept of time back to what it really is (and truly always has been): free.

Then, all of sudden, if our point of reference is the fact that time is for free, then that means it’s something money can’t buy. Not only that. If it’s for free, then how about if we gave it to one another? Generously. Abundantly. Unconditionally. That’d be pretty nice, wouldn’t it?

As for the concept of power, in my eyes, no one has ever grasped it as precisely as our main man from Germany, Friedrich Nietzsche.

In Der Wille Zur Macht, the German philosopher talks about power as this driving force that has pretty much everything to do with our own individual ambitions, desires and reasons. And from a purely empirical standpoint, I don’t think any of us can ever say he’s wrong, right? Unfortunately, power IS usually associated with the “individual”, at worst, or with the “few”, at best.

It’s always about what I want, when I want it and how I want it.

Now, what if we could change the idea we all have of “power”, and instead of thinking of the “individual”, power meant “the collective”. Can you imagine it?

What if we were able to reinterpret the concept of power through the lens of, say, the “Law of Jante”, a literary construct created by Aksel Sandemose in his 1936 book A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks, which became sort of an unspoken code of conduct in the Scandinavian society? Maybe then, we would have a different interpretation of the concept of power.

Maybe it would start being about what WE want, when WE want and how WE want.

Imagine assigning these new meanings to utterly original concepts like “time” and “power”. Maybe we would all finally be able to also conceive of a new, better world for us all, while using all of our time and power to build it.

That being said, if you ask me, being able to reconceptualize the world as we know it today, turning it into a better and more peaceful place for all of us would be worth WAY more than somehow being granted the Godly gift of coming up with utterly original concepts.

How much more, you ask? Well, about a “factorial of a mol” times more.

At least. ;o)