Dress To Impress (Part 3/3)

/In our last post, we’ve ended on Milena Canonero, and I said that in my humble opinion (that is, form someone who doesn’t understand a lot about fashion nor cinema), her work in A Clockwork Orange remains, by far, her best. Not just because it’s the most original one but also because it’s the most conceptual one.

Which shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Canonero is and always has been all about the concept. She even said it herself.

About 4 years ago, at 71 years old, Milena was the recipient of the 2017 Honorary Golden Bear for her lifetime achievement at the 67th edition of the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale). At the press conference, during her acceptance speech, she surprised everyone by saying this:

“I’m not really interested in costumes, per se.

I’m interested in the CONCEPT”.

Watch the video below to see the audience’s reaction. Some start smiling in disbelief. There’s even a guy who’s completely in shock, with his mouth wide open.

Come to think of it, this reaction from the audience kind of makes sense.

After all, there she was, being awarded for her body of work as a costume designer and she goes and says that what really interests her is NOT the costume.

It’s something else.

The concept.

Given her status, career length, depth of experience and breadth of knowledge, Canonero’s statement ‘I’m interested in the concept’ sounds like the kind of definitive conclusion that can only be reached after decades working with and learning from some of the greatest directors ever. Sort of like a pearl of wisdom that requires an entire lifetime to be forged.

That’s not the case, though.

Like I said, she’s always been that way. Canonero has always been about the concept. This has always been her approach: to follow the concept above all else.

“It’s not the costume itself that I like to do.

Of course it’s interesting, but it’s more about the meaning (behind the costume).

(The costume) serves a purpose.

(And that’s why) we have to FOLLOW THE CONCEPT”.

These were the words of a younger Canonero, in an interview with Facineshion.com, while speaking about her creative process and also about the wardrobe she created for the very first film she’s ever worked on: the unbelievable A Clock Work Orange.

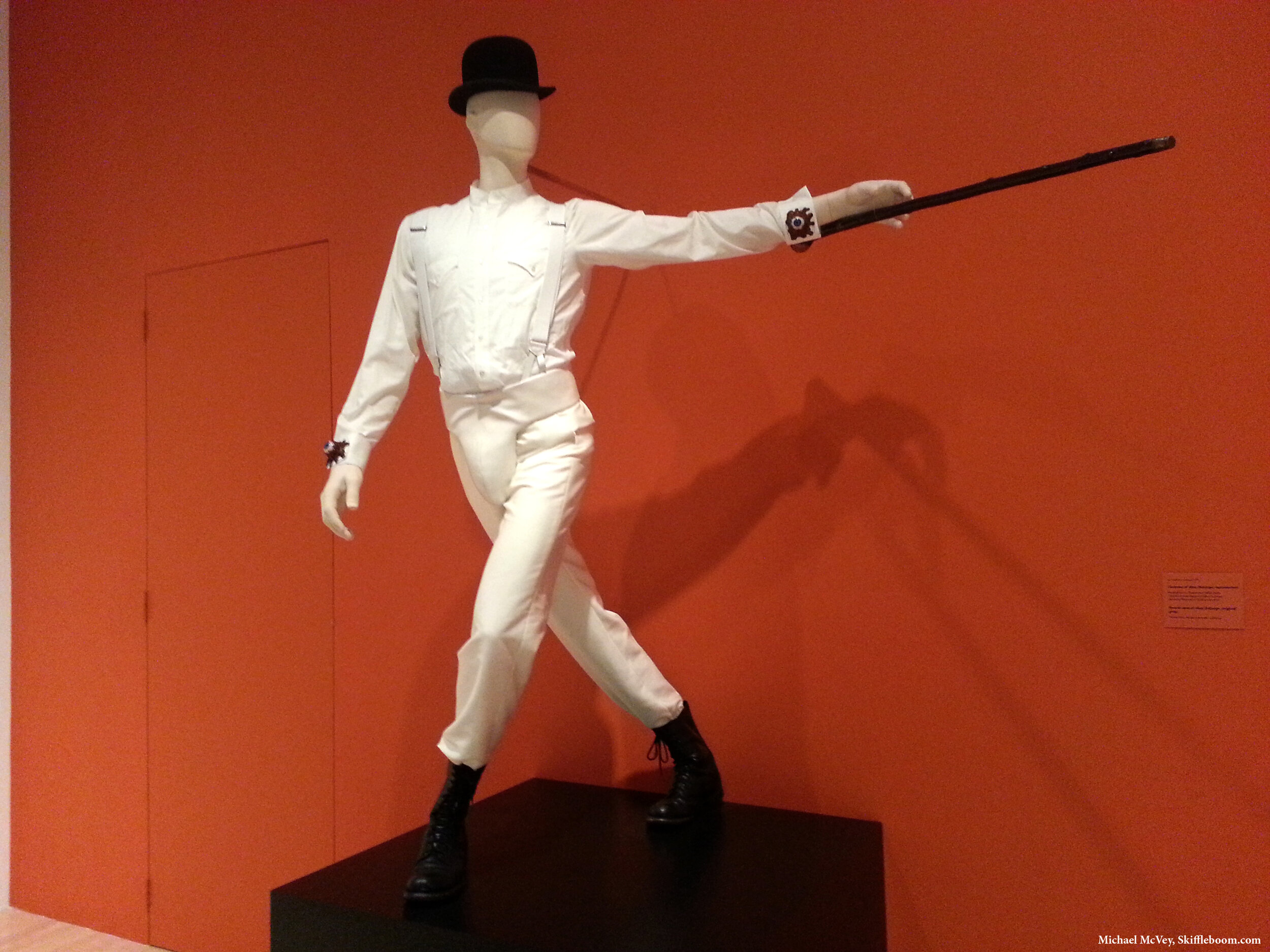

Which means that right from the very beginning of her career, her thought process was already 100% concept-oriented. And it was precisely this thought process that led her to create one of the most iconic costumes ever: the outfits worn by the Gang of Droogs.

Indecent.

Deranged.

Disturbing.

Unsettling.

Those were the words that came to my mind when I laid eyes on the costumes worn by the Gang of Droogs for the first time. Coincidence of not, these exact same words could also be used to describe the demeanor displayed by the group of psychotic and violent young men wearing those costumes.

Writer Lynn Hlaing, from F@B - Fashion at Brown (a student-run organization dedicated to bringing fashion to the Brown University community) said it best. She described Canonero’s costumes in the film as a “strange fusion of depravity and class” that “played on elements of rebellion and conformity” while being “darkly charismatic”.

Dang. Now, that’s a perfect description, right there! Well-done Hlaing.

If Canonero urges us to follow the concept, the very next question we need to ask ourselves is: so, what’s the concept behind A Clockwork Orange?

According to an article published by The New Yorker and written in 1973 by Anthony Burgess himself (he’s the author of the book “A Clockwork Orange”, after which Kubrick’s film was made), it was the power of choice (you can read the full article here).

In the book’s case, Burgess is referring to the choice between “one’s own freewill” versus the “patterns of conformity imposed by a state that has ‘the good of the community at heart’”. There’s a duality there. On the one hand, there’s the citizen. On the other, a state that goes too far, “entering a region beyond its covenant with the citizen”, as Burgess says.

That duality is all over Canonero’s costumes.

We have the bowler hat, which has been long associated with the upper classes. Then we have the bovver boots (bovver is the cockney pronunciation of “bother”), famously used by gangs and hooligans to kick people and opponents in fights. So, literally from head (the hat) to toe (the boots), we can see the conflct and the duality.

Then, there’s cane. The cane carries a lot of symbolism, as it is an item that represents the elite lifestyle. However, on Alex’s hands, it’s also the weapon he uses to attack the norms and traditions dictated by this very elite. Again, there’s the duality there.

Same thing with the cricket codpiece: cricket is a very elite sport, normally reserved for upper class individuals. In this case, Alex and his mates wear them as protective gears in their battle against, once again, the upper classes.

By mixing the braces (also known as suspenders), which were a working class item back in the 60s (as well as by the skinheads of that time) and elite items (like the cane and the bowler hat) in the same costume, Canonero intended to break the boundaries of class, while somewhat praising the working class and mocking the upper class.

Elena lazic, a French freelance film writer, put it best when she wrote an article for the British Film Institute, in 2019, about the Droogs’ style, when she said that through his costumes, Alex was “turning objects of oppression into weapons and armour for his fight against the oppressors”.

No discussion about the outfit on A Clockwork Orange is complete without talking about the famous (and infamous), iconic fake eyelash on Alex’s eye. Yes. Eye. Singular. That was also intentional. What’s with the single eyelash, anyway?

Well, instead of my writing about it, let’s listen to Canonero and Barbara Daly - the make up artist – speak about it.

Canonero said: “Kubrick gave me a lot of guidance (…) He always told me that the head is the most visible element in a film and that I should start from there. (…) I worked with Barbara (…) and we decided that (…) the long fake eyelash gave Alex a relentless, surreal look”.

Barbara added that she was looking for something to go with Milena’s incredible costumes: “It had to be something strangely extraordinary (…) something weirdly dramatic. So I said to Stanley, ‘what about trying fake eyelashes?’ and he said, 'Let’s look and see’. (…) (We tried it and) we all thought ‘That’s it!' It’s sinister”.

Canonero works with a purpose. Her conceptual approach doesn’t allow her to do otherwise. The eyelashes. The codpiece. The cane. The hat. The braces. The bovver boots. Everything was intentionally chosen as part of the development of the character and as a reflection of the character’s psychology. There’s meaning behind every single one of her designs.

There’s also research: a LOT of it.

Just like Ruth Carter, Canonero is a researcher at heart.

A great example of her commitment to research can be seen in the costumes she designed for the film Out of Africa (1985), starring Meryl Streep and Robert Redford. According to an article from the New York Times titled Milena Canonero: Fashion On And Off The Court, published on Feb 11, 1986, here’s what her research work looked like in the pre-production for the film:

“After reading the script, she studied the garb of tribes native to Kenya, as well as that of the early-20th-century white settlers. She went to libraries, embassies and museums in Nairobi and London. She also talked to the contemporaries of the author, Isak Dinesen”.

''You find this incredible guy who lives all alone in Yorkshire who's got the biggest collection of Somali references,'' she said. ''You photograph everything. No matter how well you know a certain period, you still go into it.''''Once I've done my research,'' she said, ''I go into what each character should wear”.

By the way, that’s another thing Canonero and Ruth Carter have in common: films that take place in Africa.

In Canonero’s case, we’re talking about an epic drama that takes place in Kenya and tells the story of an aristocratic woman (played by Meryl Streep) who is torn between two choices: keeping her fancy and sophisticated (albeit extremely boring) lifestyle or giving it all up so that she can experience love and expand her own world next to a free-spirited hunter (played by Robert Redford), who lives a much poorer, much simpler, but extremely exciting, life.

The film is called Out Of Africa.

In Carter’s case, we’re also talking about an epic adveture, which takes place in the fictional African country of Wakanda, and tells the story of a prince turned king (after the passing of his father) and who is torn between two choices: keeping the secrets, wealth and super high tech innovations of Wakanda within the limits of Wakanda (as his father had done before him) or opening Wakanda borders to the world, revealing its rich heritage and sharing its resources with the other Nations of the world.

Yes. I’m talking about Marvel’s marvelous blockbuster, Black Panther (2018).

Now, I could sit here and spend the whole day writing about the wardrobe Carter created for the film. I love talking about it and I love learning everything about it. In my eyes, it’s one of the most comprehensive and beautiful works of costume designs in recent history. No wonder she won an Oscar for it.

But since this 3-post series has gotten way too long and I’ve taken way too much of your guys’ time already, I’ll narrow things down a bit and focus on something more specific: the fact that there’s a lot more to concepts than meets the eye. And that it is precisely on this wider, deeper side of a concept – the one lying beneath the surface – that we find its true value.

Carter’s work on the Black Panther is the prime example of that.

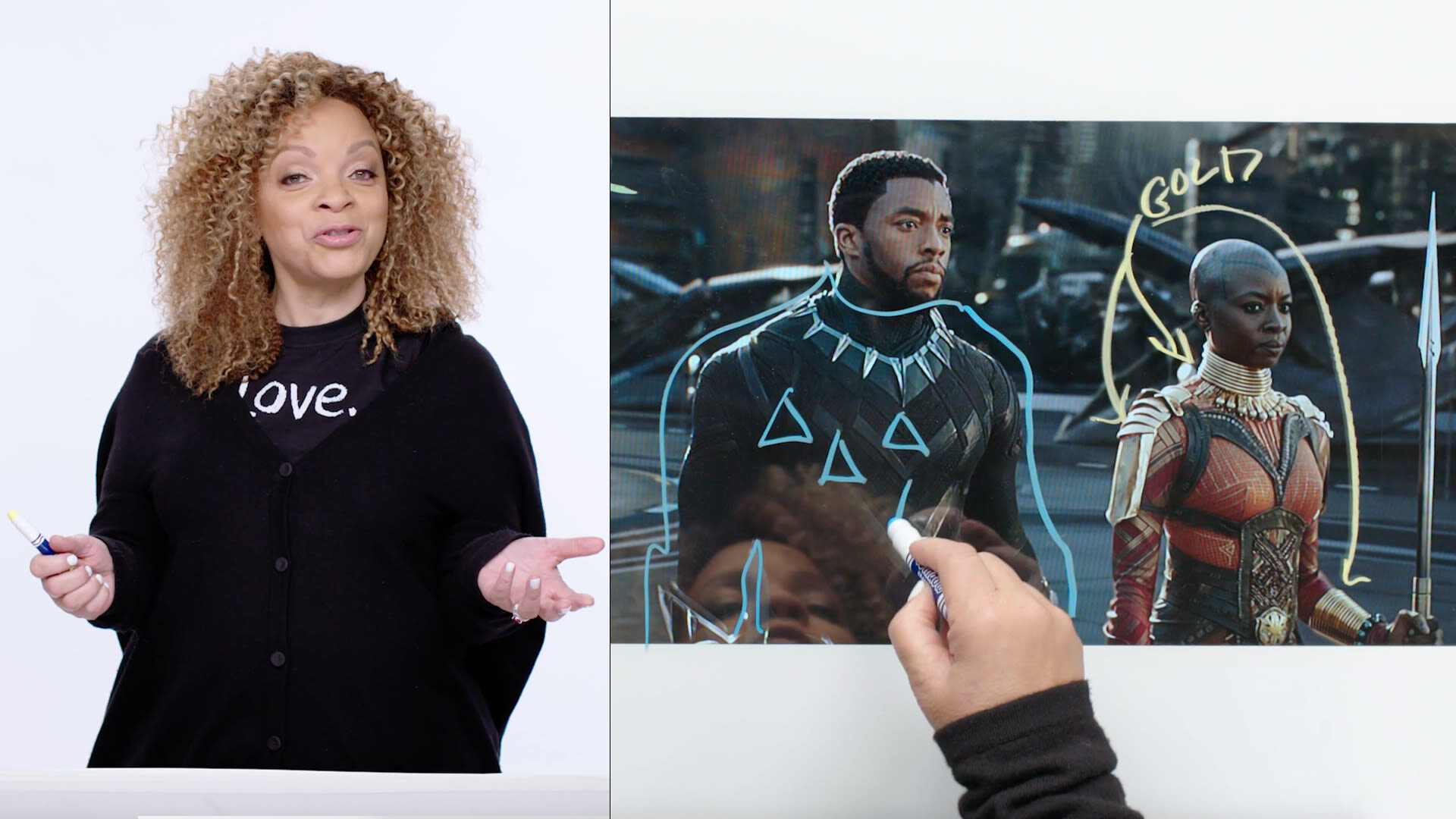

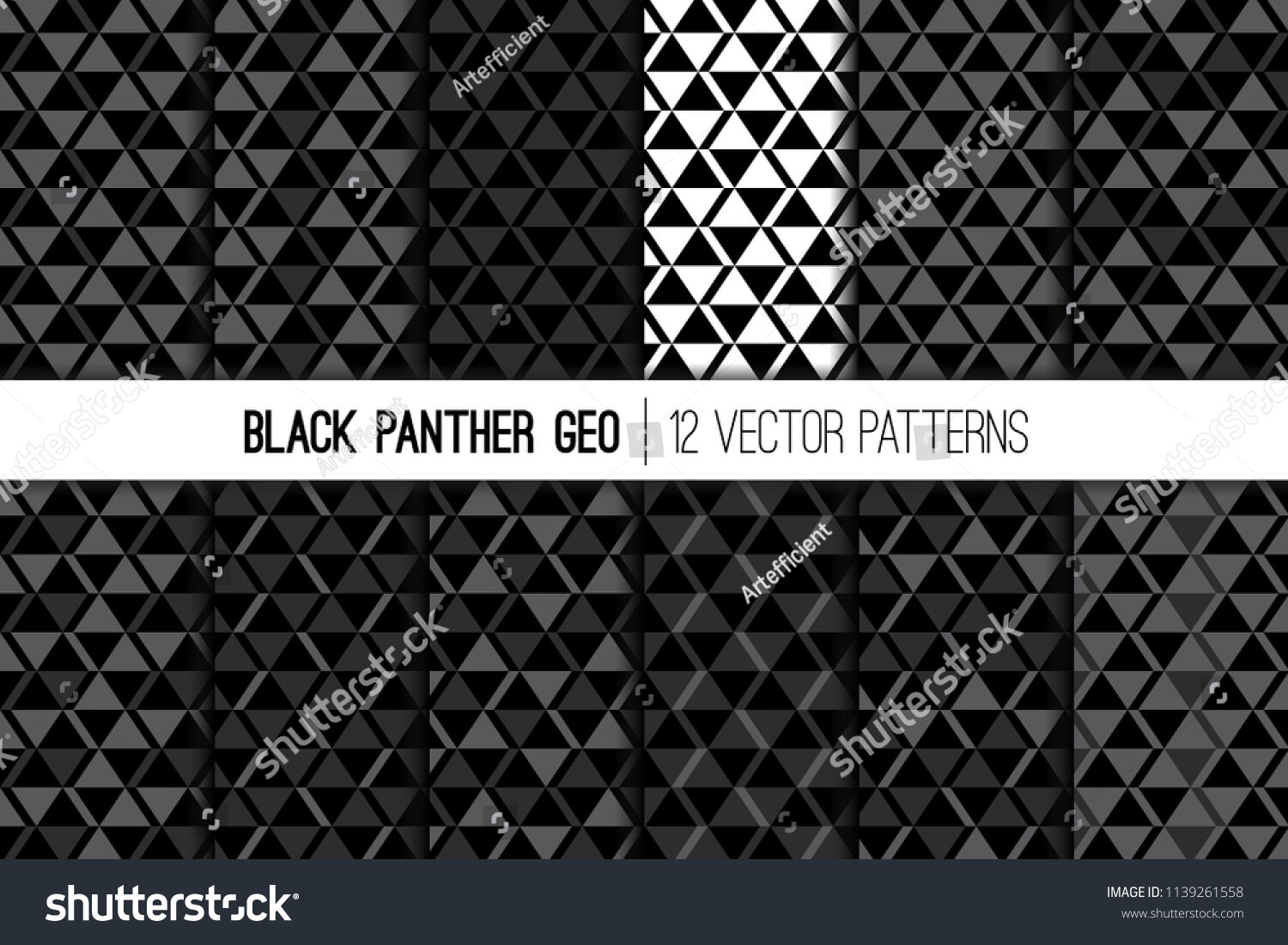

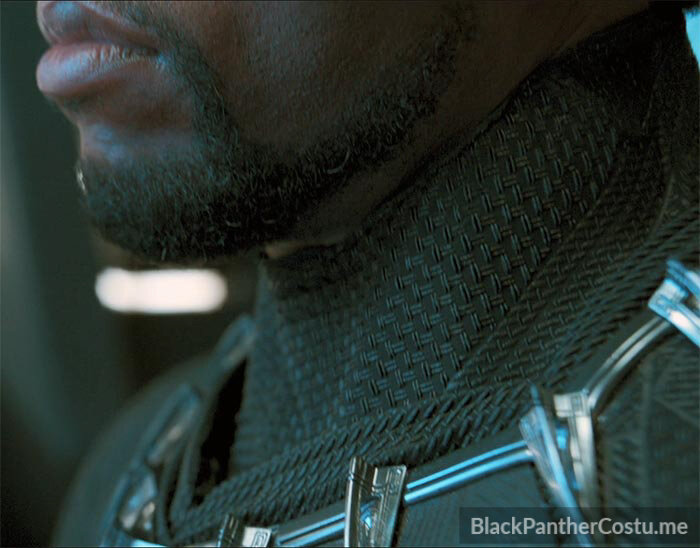

For instance, let’s look at the triangle pattern imprinted on T’challa’s (the prince turned king) panther suit.

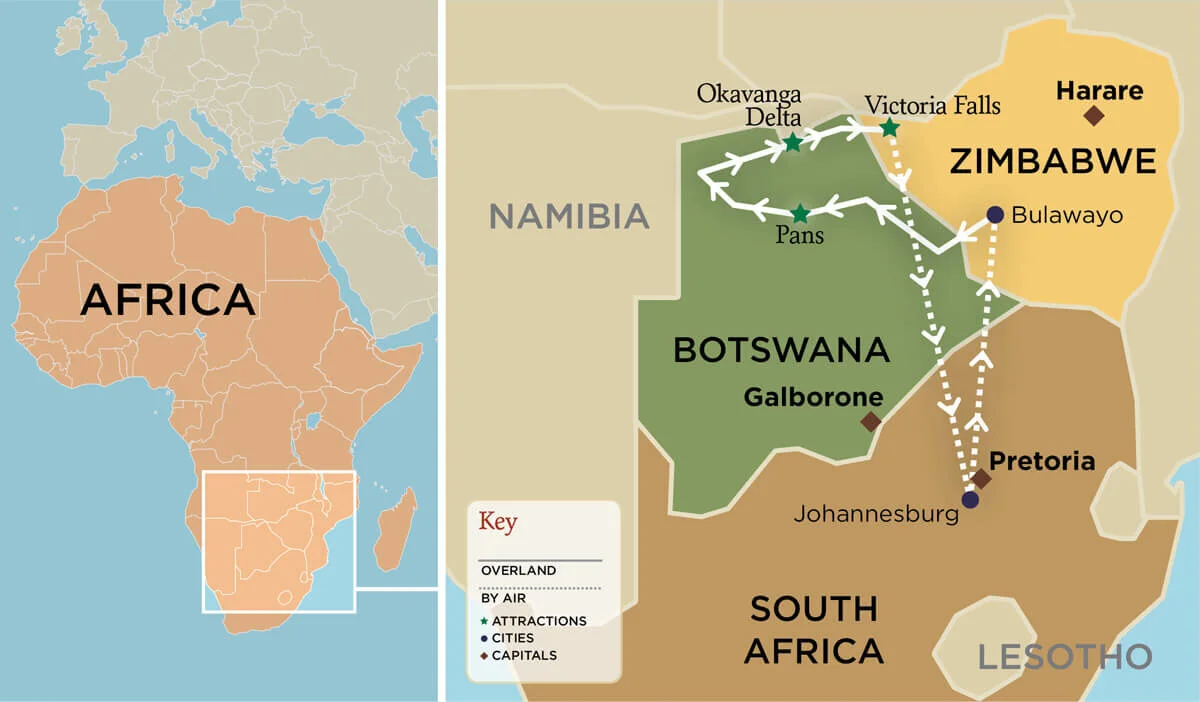

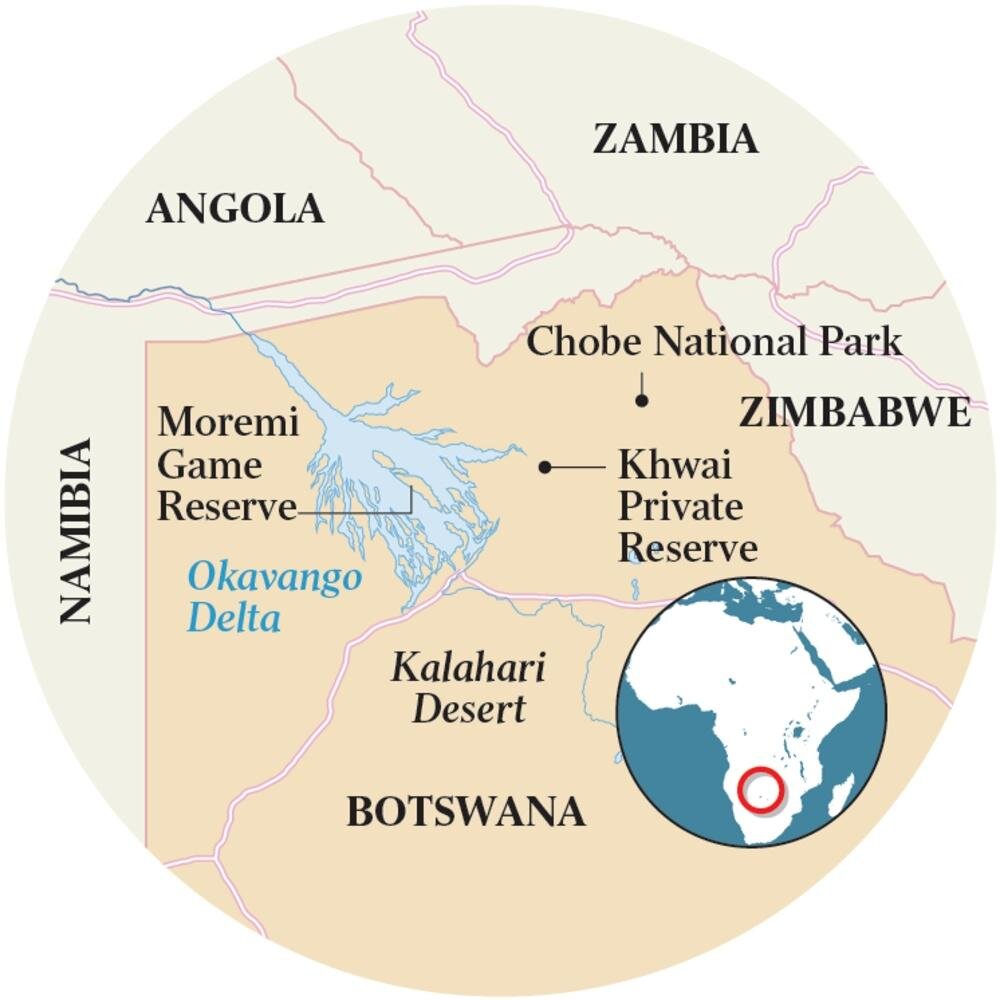

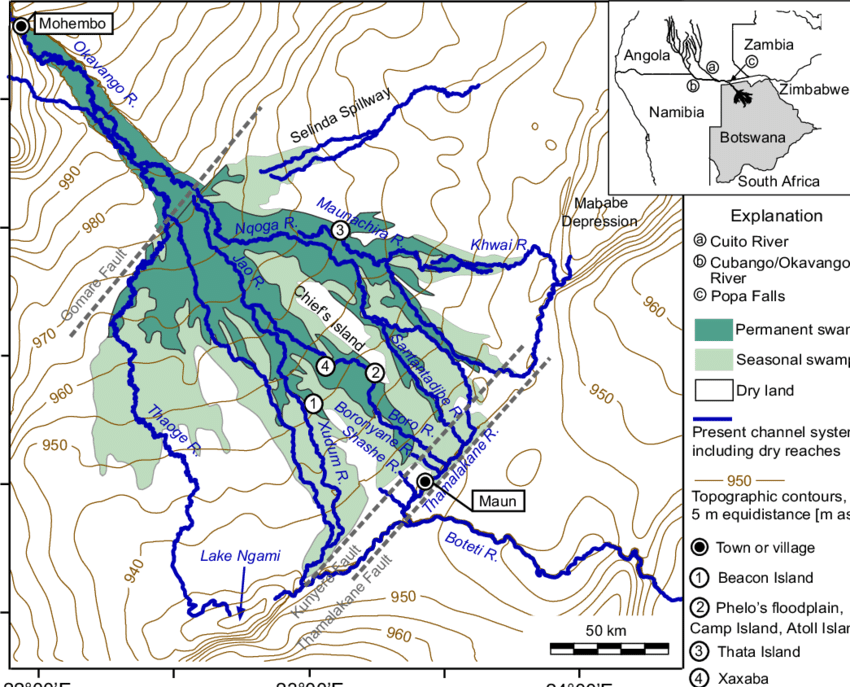

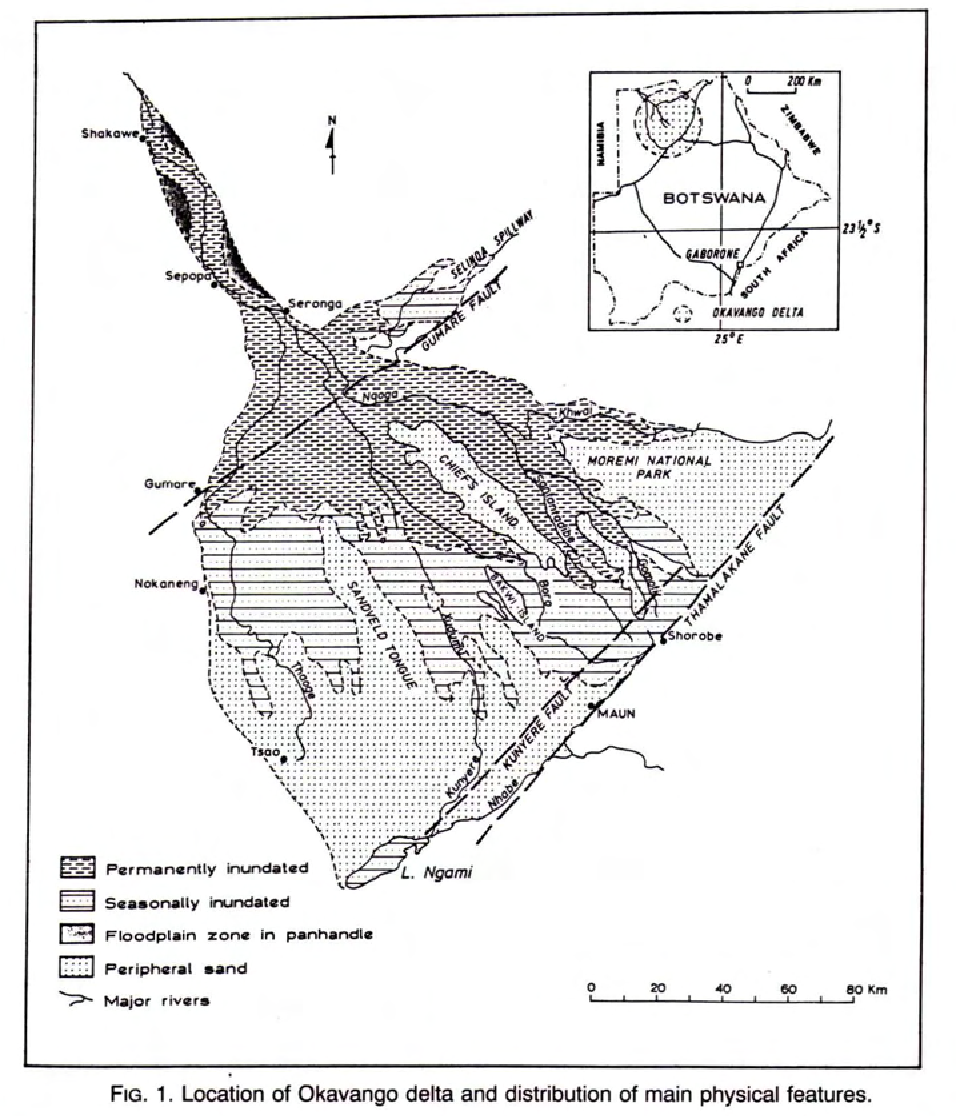

This pattern was inspired by the Okavango patterns. Okavango is the name of the largest inland Delta in the world and it’s located in northern Botswana. It’s known for being a sanctuary to some of the world's most endangered animals, like cheetahs, white rhinoceros, black rhinoceros, African wild dogs and lions.

The Okavango Delta – in that sense – is a symbol of Africa’s incredibly rich wildlife and diverse ecosystems. It’s also legally protected through Botswana’s Wildlife Conservation and National Parks Act of 1992 and an associated Wildlife Conservation Policy.

Deltas have a triangular shape, much like the African continent. And that, according to Carter, makes the triangle the “sacred geometry of Africa”. Incorporating the shape to the Black Panther’s uniform represented T’challa’s status as a true African king, who had the legal duty to protect the life and diversity of all the different tribes of Wakanda.

Isn’t it absolutely wonderful how a simple geometrical shape can carry so much meaning?

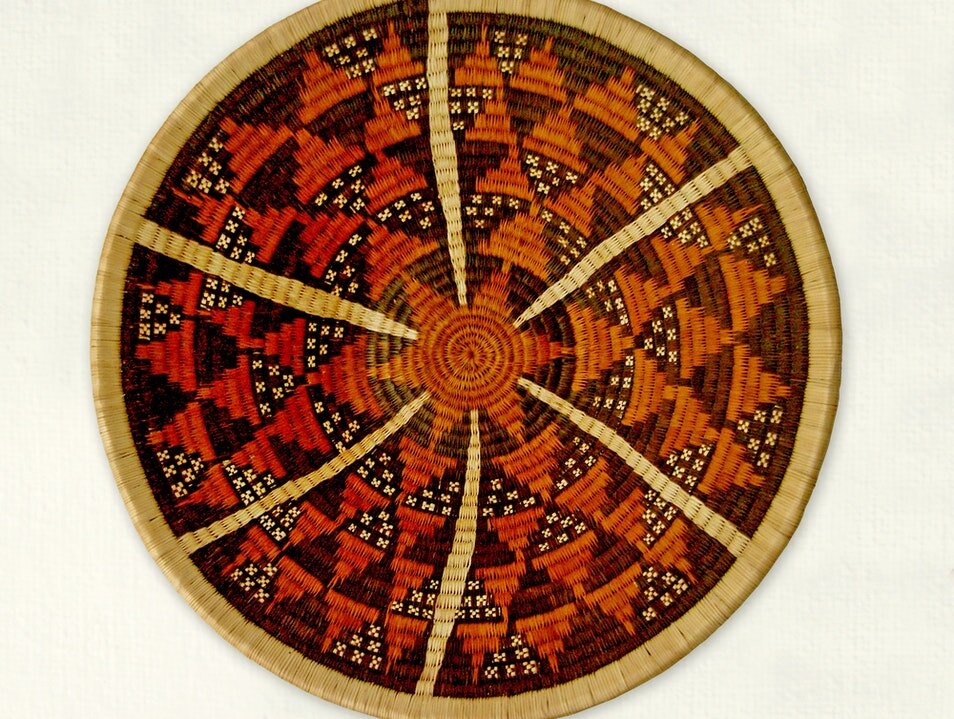

You guys want to see another example? Let’s take W’kabi’s costume, for example.

Why is the costume a blanket? Why is it blue? And what are those metallic symbols emblazoned across the blanket?

W’Kabi is part of the Border tribe, which was inspired by the real Lesotho people, more specifically, the Basotho tribe. Lesotho is a high-altitude, landlocked kingdom encircled by South Africa. It’s the only country in the world to have its ENTIRE territory located above 1.000 meters / 3.281 ft. (the lowest point in Lesotho is situated at 4.593 ft.).

Because it’s located on a mountainous region, where the weather is usually colder, people from Lesotho wear blankets as coats. Just like the members of the Border tribe, which also live on the higher grounds of Wakanda.

The Border tribe inhabits higher altitudes because their main function in Wakanda is to watch and protect the borders from foreign threats. And it’s easier to spot enemies coming from afar when you’re doing it from a higher vantage point. In that sense, the Border tribe is the one with the authority to dictate who gets to cross the border and who doesn’t.

In Ryan Coogler’s eyes (Coogler is the director of the film), authority and protection are tasks reserved to the police. And the police, in the United States, wear blue. Also, the real Lesotho flag has a very distinct shade of blue, which represents sky. Since the Border tribe lives the closest to the sky and was inspired by the Lesotho people, blue was the color of choice.

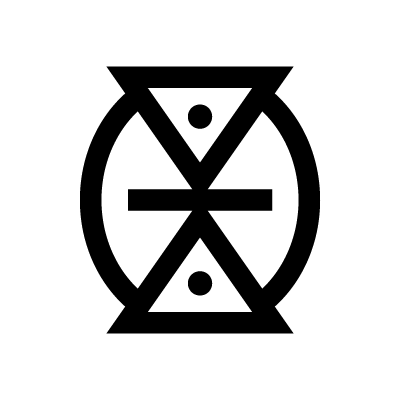

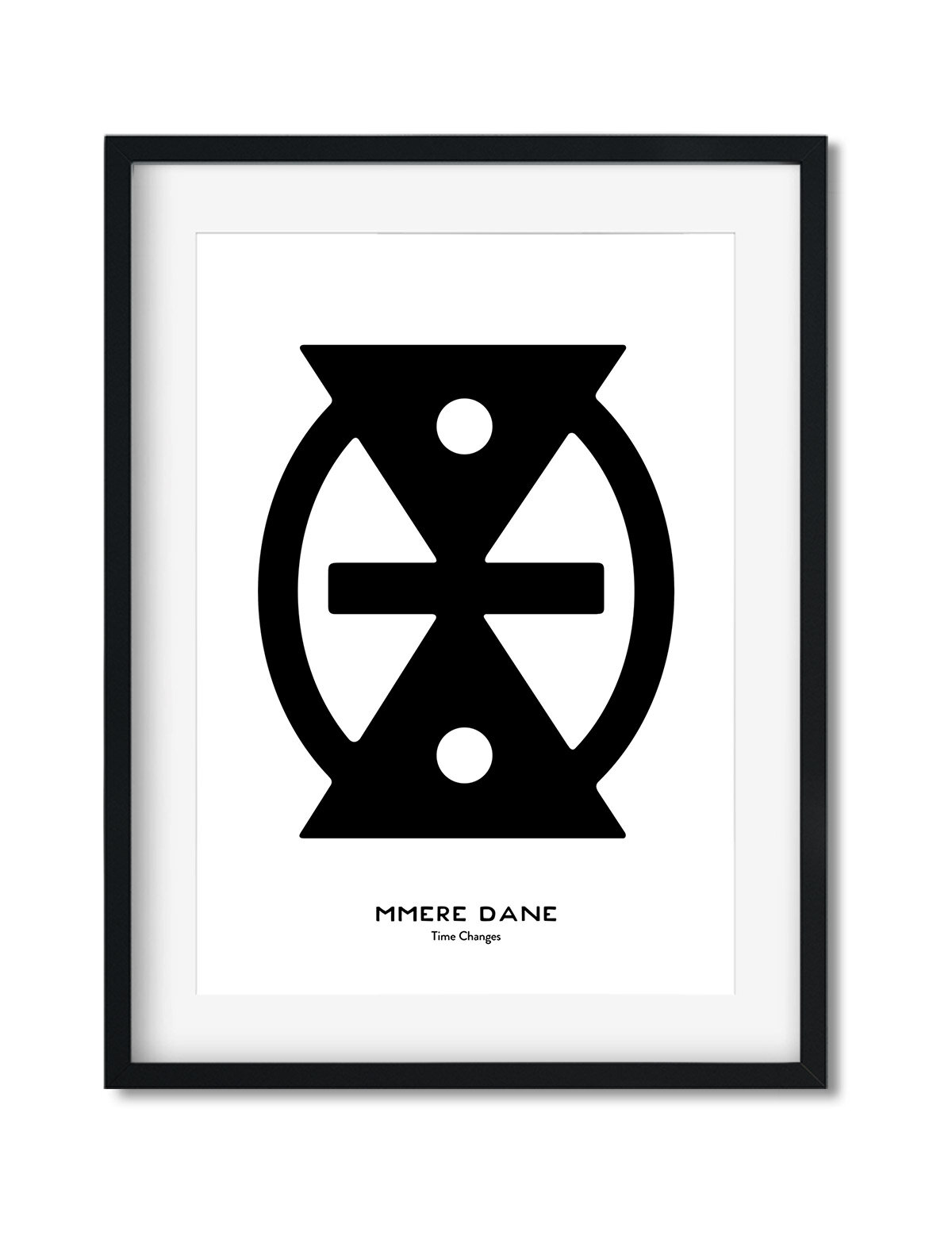

The symbols on W’kabi’s blanket are known as Adinkra symbols. Adinkra symbols are a kind of “writing system”, believed to have originated in the region that now comprehends the countries of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. The Akan people, one of the main ethnicities of West Africa, are credited for having invented these symbols, around the early 1800s.

In a way, Adinkra symbols remind me of the first ancient Chinese characters, as they represent universal concepts: leadership, family, strength, love, independence, etc.

In one of the most dramatic scenes of the film, we can see members of the Border Tribe engaging in a grueling battle against T’Challa himself. It’s a rupture in the status quo. Before, the Border Tribe answered to T’Challa. Now, it’s rebelling against him. Times are changing and this fight is a sign of this change. As the members of the Border Tribe stand next to each other, using their blankets as shield, we see a big symbol standing out. It’s similar to the Adinkra symbol that represents “change”, or “times change”.

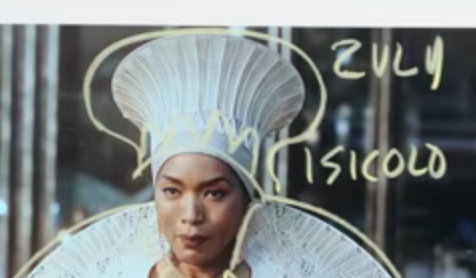

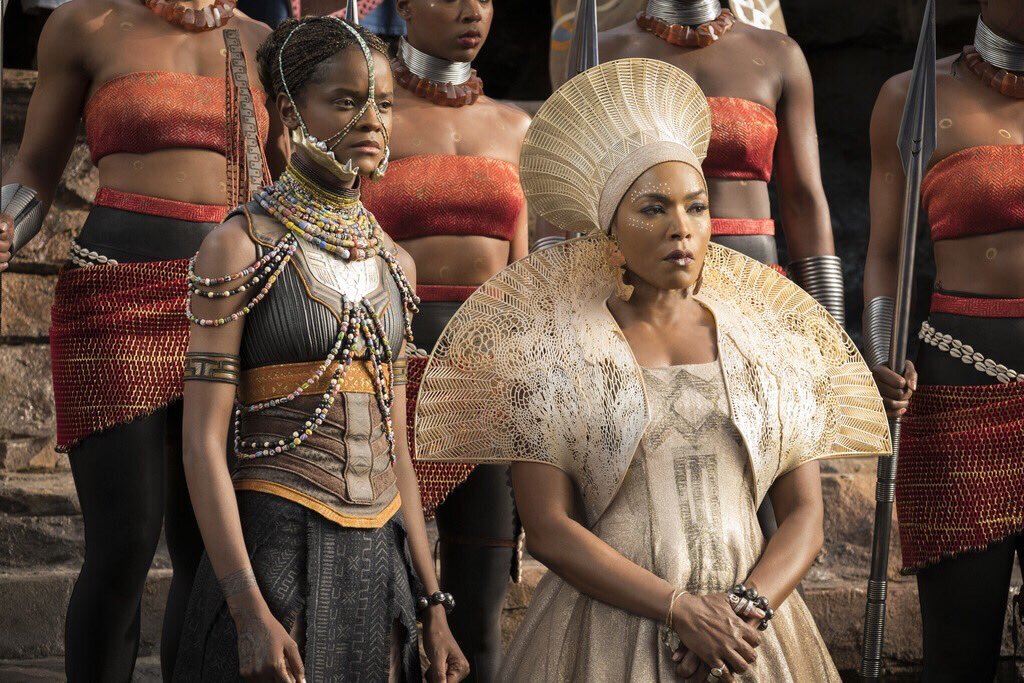

Finally, one last example: the beautiful hat worn by T’challa’s mother, Ramonda, Queen of Wakanda.

The first time we see Ramonda in the film is truly a powerful sight. Even though we’re just being introduced to her, we somehow know she’s not like the other inhabitants of Wakanda. To her right, there’s Ayo, one of the Dora Milaje (the protectors of the Black Panther). To her left, there’s Shuri, T’Challa’s sister, wearing a T-shirt with an Adinkra symbol that means “purpose”. And in the middle, there she is: the queen.

We may guess she’s some kind of royalty because of her shoulder mantle. Shoulder mantles have been used as a royal garment across many cultures since time immemorial. But it’s the hat that gives it away: that’s’s the crown. It was inspired by the Isicholo, which is the Zulu hat worn by married woman in South Africa.

And when I say it’s a crown, I mean it. Take a look at the picture below and you’ll understand what I’m saying.

When Ruth Carter designed it, she wanted the Isicholo to be an extension of an actual crown. And she was unapologetic about it. So, to make sure that happened, she worked with contact Austrian architect Julia Körner, an award-winning designer internationally recognised for design innovation in 3D Printing. Together, they created a truly wearable piece of art, using a polymer that can bend easily but is still strong.

Now, let’s be honest.

How many of you already knew about or were aware of all these things I just wrote about? The crown on Ramonda’s Isicholo, the color of W’Kabi’s blanket and the triangle pattern on T’challa’s uniform?

Ok, I’ll go first: I didn’t. I had absolutely no idea. I didn’t know about any of that.

And yet, it was all there: months on end of strenuous and rigorous research, a very specific intent from Carter’s part (she wasn’t looking for African diversity; she was aiming at African representation) and all the different meanings behind each costume.

Unbeknownst to (most of) us, all those things were there.

You know what else was there?

Carter’s massive repertoire, unparalleled experience, immense talent and huge knowledge about costume design. All the lessons and memories she accumulated by working in so many different films, with so many great directos. All those things, they were also there.

And when we put all those things together, we realize the REAL value of concepts (in this case, the ones created by Carter). We don’t immediately see it. It’s not obvious at all. But it’s there. Super there. And when it hits us, it hits us like a freaking iceberg, harnessing all that power that’s lying below the surface to shatter our perceptions. And blow our minds.

“I respect the audience’s intelligence a lot, and that’s why I don’t try to go for the lowest common denominator.”

I’m one of those people who blindly believe in the notion that there’s something incredibly powerful about creative works and artistic expressions that are NOT OBVIOUS and that require a bit of effort (and repertoire) to be fully understood. And the reason why I say this specific kind of art form is incredibly powerful is simple.

Because they make us think. They encourage us to question. They make us go after references and information we didn’t previously have. They make us reflect on issues we never dared or cared to reflect on before. They strengthen and sharpen our critical thinking. They prevent us from aiming at the lowest common denominator.

And during this whole process, I like to think that they also make us better as people and as human beings.

I’m not sure where Carter got this from: the ability to create beautiful, conceptual pieces of wearable art that make us think.

Her costumes are definitely NOT obvious. Not in the slightest. They’re super well thought out. They’re intelligent. They’re insightful. There’s always a hidden message somewhere, flying under the radar. Things that we may not perceive right off the bat, but that will marvel and surprise us if we decide to put forth the effort and dig just a little bit deeper to find them.

Maybe she got it from Spike. Who knows? If you guys remember the hyper provocative ending of Do The Right Thing, Spike presents us with two quotes that address the relationship between violence and its role in the context of racial justice: one belongs to Malcolm X (advocating violence as self-defense) and one is attributed to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr (advocating peaceful protest).

Spike doesn’t give us an obvious answer. He invites us to think about each quote, reflect on them and reach our own conclusion. As he once said, he refuses to spoon-feed his audience, as this would be the equivalent of underestimating the audience’s intelligence. I agree.

I once said that conceptual thinking is all about thinking about the whys. What I forgot to mention is that, in that sense, conceptual thinking is a universal inalienable right. And if it isn’t, it should be. We all have the right to do so. We were born with it and we will die with it. And any kind of attempt to deprive us from exercising this right should be severely admonished and immediately abhorred.

Now, why some people willingly CHOOSE to not ask why, I’ll never know. Then again, they have the right to do so, right? They have the right to choose to NOT ask why. And no one can force them to do otherwise.

Fortunately, we have people like Carter, Canonero, Gaultier, Pasztor and Mabry, who can’t help BUT ask “why” during their creative process. And I say “fortunately” because in their tireless attempt to search for answers, they’re able to find purpose for their wardrobe, give meaning to their designs and CREATE VALUE for their costumes.

Now, let me be super clear: this value has nothing to do with the production cost of a particular costume (well, maybe it does a little bit, considering that the first Black Panther suit costed about USD 350.000!). But I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about a totally different kind of value.

I’m talking about the kind of value that, for example, a black belt (which is nothing more than a – usually very cheap – piece of fabric tied around a person’s waist) has, both inside and outside the mat.

Behind the aesthetics of a black belt lies an entire set of ethics.

What I mean by that is that a black belt is something that demands a certain demeanor from the person wearing it. It symbolizes the journey that the person wearing it had to go through to be able to wear it. Because of this journey, this person wearing a black belt can have a very specific effect on the people around him or her: love, admiration, respect, fear, envy, etc. And this effect makes these people act or react a certain way.

Now, replace “Black Belt” with “Black Panther suit” and read the paragraph above again, please. See where I’m going with this?

Costumes are created to help actors get into character and deliver the best performance possible. They’re specifically designed to serve the narrative of the movie. Their purpose is to help sell the story being told on screen. After all, the more the audience buys into the story, the better the film will do. The more money it will make. And the more people it will touch.

That’s why the costume designs of Carter, Canonero, Gaultier, Pasztor and Mabry are so, so valuable: because they mean something for the actors. They mean something for the film. And eventually, they end up meaning something for us all, the audience.

Going back to the beginning of the first part of this 3-post series, fashion – as a creative form of expression – has this unique power: the clothes you wear on your body is usually a reflection of the emotions you do (or would like to) wear on your sleeve. Honestly, it doesn’t get any more conceptual than that.

As protagonists of their stories, each of the characters we’ve seen on this series of posts had their own pick. Malcolm X had the zoot suit. Leeloo had the bandage/bondage-like bodysuit. James Dean had the iconic red jacket. T’Challa had the Black Panther vibranium suit.

How about you? As a protagonist of your own story, what is your pick?

What is that ONE piece of clothing that truly reflects who you really are (and not what people say you should be or think you are)?

What is the one item that is always there in your closet and that, in your head, never goes out of style, simply because it means a lot to you, and therefore, it is valuable to you? Please, write down on the comments below. Oh, and of course, if you don’t mind, tell us why. I’d love to hear from you.

In the meantime, I can tell you which clothing item I would pick (and still DO pick) to wear once every single day and twice on Sunday. That one item that has been a constant in my life since the 90s.

You’re probably guessing already, right? That’s right. You got it.

It’s my flannel plaid shirt. Why, you ask?

It’s because… you know what?

Nevermind. ;o)