Dress To Impress (Part 2/3)

/In the last post, we got to learn a bit more about Ruth Carter and her work on Spike Lee’s 1992 Malcolm X. Mostly, we learned about her conceptual approach on the film: diving into research and making sure every single costume meant something to the character and played a role in the scene.

Costume designer Moss Mabry did the same in Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

His research involved spending days on end at Los Angeles high schools, observing the way teenagers dressed. Together with director Nicholas Ray, Moss decided to use the color red to create symbolism and touch on the subjects of juvenile delinquency and family conflicts.

The costumes helped tell the stories of Jimmy (played by James Dean), Judy (played by Natalie Wood) and Plato (played by Sal Mineo).

In Jimmy’s case, his red windbreaker represented the height of his rebellion and anger. In Ray’s words: “When you first see Jimmy in his red jacket against his black Merc, it’s not just a pose. It’s a warning, it’s a sign”.

For Judy, her bright red coat and red lipstick symbolized a person that, on the outside, seemed sexually confident, but on the inside, was confused and frail.

Finally, in Plato’s case, his red sock hinted at tragedy and death.

In all three cases, red was intentionally used to represent the characters at their most emotionally fragile and defiant moments.

Just like Mabry used colors to conceptually help enrich the story in Rebel Without a Cause, Hungarian Beatrix Aruna Pasztor used something much simpler: T-Shirts. She is the costume designer behind the wardrobe we see in Good Will Hunting (1997).

The film tells the story of Will Hunting, a twenty-year-old self-taught genius, who has an incredible gift for mathematics, but works as a janitor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The story begins with Will as a troubled, confused and lost young man with a knack for getting into fights. As the movie progresses, we see Will maturing, as he confronts his past, evaluates his relationships and starts thinking about his intellectual potential and his future.

There’s a video posted by GammaRay channel, titled How The Fifth Element Changed Fashion, in which we learn more about Pasztor’s intentions when she created the designs we see stencilled on the T-Shirts Hunting wears throughout his journey of self-discovery: she wanted to show the evolution from a world or chaos to a world of order.

Take a look at the pictures below to see how she beautifully – and conceptually – succeeded at that.

Speaking of the The Fifth Element (1997), this movie is one of the big reasons why the 90s were, are and will always be the best decade ever. ;o)

I still remember the first time I watched it: my mind was totally, totally blown.

The plot is super fun – it is action-packed, insanely absurd, funny, romantic, and, believe it or not, even a bit philosophical. But what really blew my mind wasn’t any of that. It was something else: it was the outrageously creative costumes in the movie.

When I first watched Malcolm X and Rebel Without a Cause and Good Will Hunting, I didn’t really pay attention to the costumes. To me, they were simply a small part of the mise-en-scène. Of course, after I learned more about the subtle and hidden messages conveyed by the designs created by Carter, Mabry and Pasztor, I realized I was wrong. Those costumes, just as the characters wearing them, told stories. They mattered.

That wasn’t the case with Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element.

From the get-go, from the very first scene in Egypt all the way to the ones that take place in 23rd century New York, I just knew something unprecedented was happening. Unlike any of the previous cinematic experiences I had ever had, I realized I was paying as much attention to the costumes as I was to the plot.

The genius behind the astonishing and undeniably original costumes of the film is a man most commonly known as the enfant terrible of the fashion world: Jean Paul Gaultier.

Together with French director Luc Besson, Gaultier conceived more than 5.000 (yes, you read it right: five THOUSAND) sketches, in order to dress every single person on the set. From the superstars to the extras, he made sure to create a single, unique costume for every person on the set. Now, here’s the craziest part: only 1.000 of those sketches were used, meaning that 4.000 didn’t even make it to the screen!

Canadian art curator Thierry-Maxime Loriot, who was responsible for “The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk” exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2011, spoke about Gautier’s work for the film:

“A thousand costumes is like 10 collections, but (he did it) all for one movie. It’s an incredible amount of work people don’t even know about. For a thousand costumes, he may have even done 5,000 sketches before narrowing it down”.

For years, movie experts and fashion magazines have been describing Gaultier’s designs in the film in a myriad of ways. Provocative. Ostentatious. Tacky. Vibrant. Flirtatious. Sumptuous. Elegant. Eye-catching. Even ceremonial.

Personally, I agree with the way Grailed, a website specialized in buying and selling high-end, secondhand menswear and streetwear, described it: “Gaultier’s work proved to be one of the most ambitious conceptual achievements in the history of cinematic wardrobe”.

Conceptual.

I agree. 100%.

Because it’s true.

PEDRO almodóvar, victoria abril and jean paul gaultier (kika, 1993)

“The costumes Jean Paul Gaultier designs are wonderfully beautiful and ABSOLUTELY CONCEPTUAL at the same time. Almost no one else is able to combine both in the same garment.”

“The costumes Jean Paul Gaultier designs are wonderfully beautiful and absolutely conceptual at the same time. Almost no one else is able to combine both in the same garment. ” - Pedro Almodovar

Gaultier’s work on The Fifth Element is as conceptual as it gets, in the sense that:

Behind every sketch, there is meaning.

Behind every design, there’s significance.

Behind every costume, there’s purpose.

This powerful trifecta creates value for the characters, and most importantly, to the story that’s being told.

Let’s look at three characters that perfectly illustrate each of the bulletpoints mentioned above: central protagonist Leelo (played by a 19-year-old Milla Jojovich), central antagonist Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg (played wickedly by British legend Gary Oldman) and the comic relief of the film, Ruby Rhod (perfectly portraited by comedian Chris Tucker).

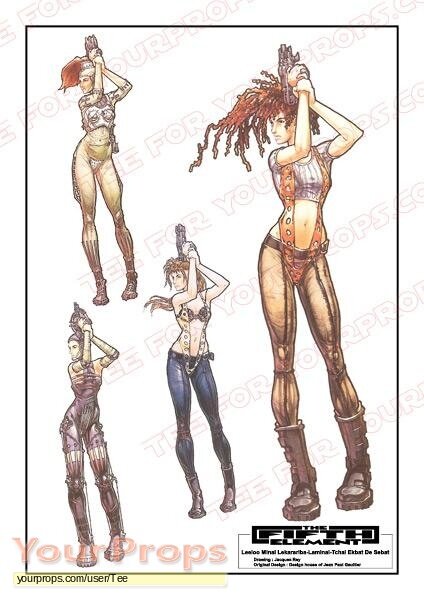

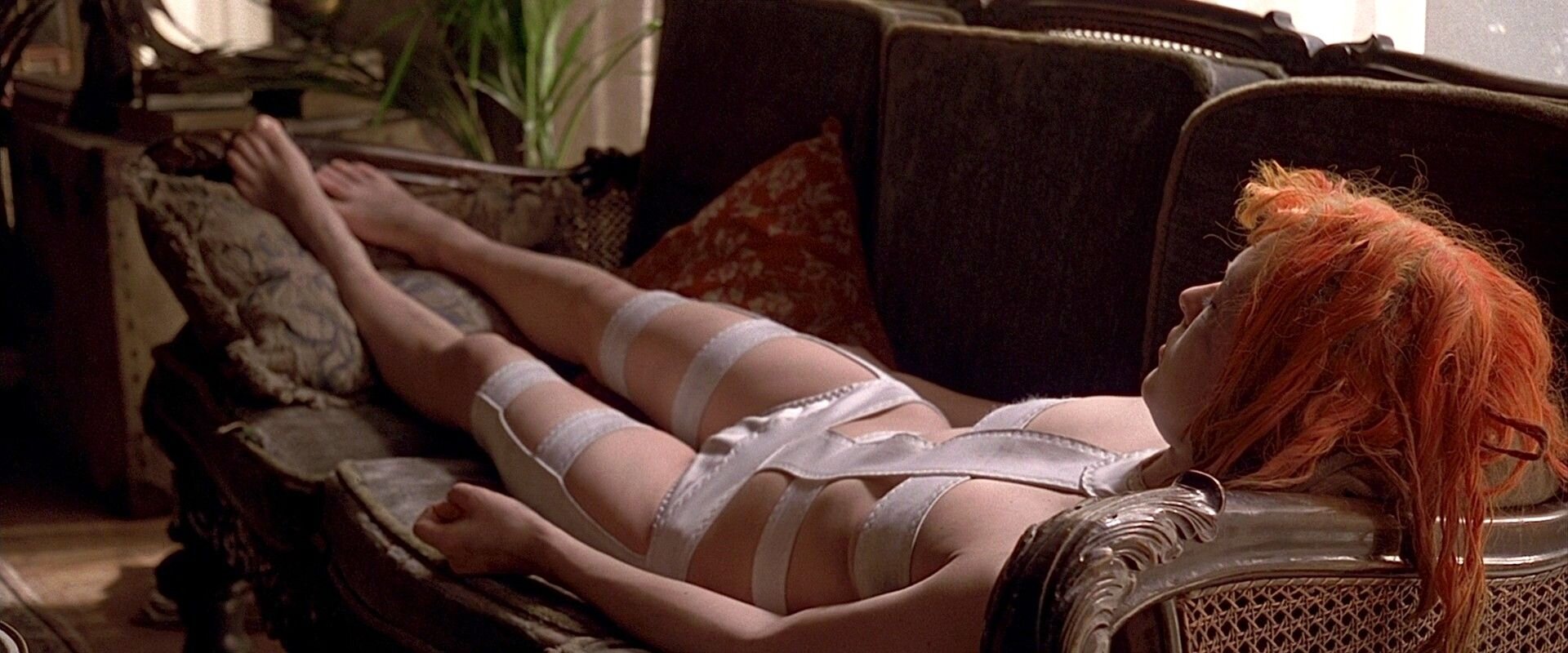

Leeloo first.

Perhaps the best way to describe Leeloo is that she is sort of the human personification of an extraterrestrial divine being. The first time we see her, she’s “being born” in what seems to be a cryogenic chamber. And just like all newborns, she’s…naked.

That is until Gaultier decided to turn the straps that are keeping Leeloo tied to the chamber into a white bondage/bandage-like bodysuit. If you’re familiar with Gaultier’s body of work, you know the bondage aesthetics has always been an integral part of his creations.

But in the case of Leeloo, it was more than that.

He didn’t go for the bondage lines out of habit. He wanted the design and the color of Leeloo’s outfit to mean something. As writer Marianne Eloise wrote in Dazed Magazine: “Jovovich’s nudity and near-nudity, intended to show her vulnerability and naiveté”. The white color of her outfit, in contrast to her super bright orange hair, was intentionally picked to symbolize Leeloo’s innocence.

There you go. MEANING.

Bulletpoint number one: check.

Then we got the maniacal industrialist Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg.

His only goal is to destroy life on Earth, and he counts on his faithful henchmen to do as much evil as possible, the same way a mafia boss does. To convey that message, Gaultier dressed Zorg with a futuristic version of the pinstripe vests and suits worn by gangsters and mobsters of the 1930s.

See? Every bit of Zorg’s clothing matters, from his vest down to the tiniest accessories, like the ring he wears on his pinky. There’s a very strong significance behind them.

In Tony Earnshaw’s 2016 book “Fantastique: Interviews with Horror, Sci-Fi & Fantasy Filmmakers – Volume 1”, Gaultier talks about how the rolled gold ring became of part of Zorg’s costume:

“He was one of “whom” I made the most sketches. (…) The character was very precise: like a monster, very fascist. (…) And with the rolled gold, which is something militaristic that goes with the fascism type, that was a little accessory that made him like a monster”.

I can’t help but picture someone asking Gaultier: “What’s up with the rolled gold on Zorg’s pinky? Does he really need to wear it? The audience will barely see it! Does it matter at all?” only to hear Gaultier’s response: “Yes, it matters a lot, because there’s a lot of significance behind that ring. So it’s important that Zorg wears it.”

Boom! SIGNIFICANCE.

Bulletpoint number two: check.

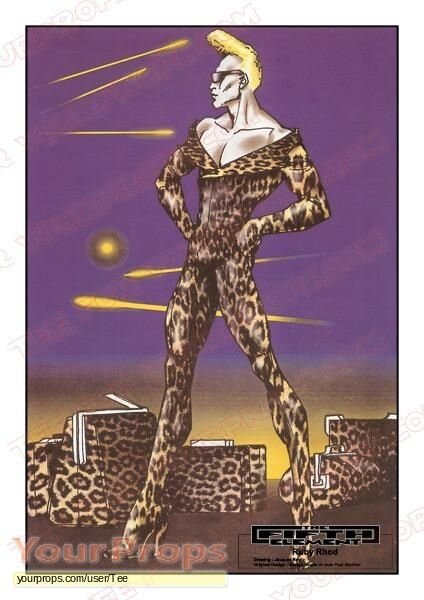

Finally, Ruby Rhod, one of the most flamboyant, hysterical and extravagant characters ever conceived in the history of cinema. Jean Paul Gaultier never had any doubts about what Rhod’s costumes should look like.

In the “Fashion Element” featurette of the film’s DVD, Gaultier talks about Rubdy Rhod:

“He (Ruby Rhod) sees himself as something between Prince and Michael Jackson.

I say maybe he’s not so much like Michael, but rather, Janet.

Maybe even LaToya Jackson! (laughter)”

Which means that from the start, the purpose was to create a wardrobe that would look and feel gender bending. Now, this is where Jean Paul Gaultier shines, this is when he is at his best and in his own element (no pun intended): when he gets to explore, test and break the boundaries of gender, culture and ethnicity. He’s an absolute MASTER at that.

So, from the “all-leopard print one-piece costume with the wide-brim neckline”, combined with a cane and the bleached blond-ish quiff to the black wide-necked satin top adorned with scandalous red flowers, everything was designed to serve one purpose: to be gender bending. A purpose that was also achieved thanks to Tucker’s impeccable performance.

Voilà. PURPOSE.

Bulletpoint number three: check.

Today, The Fifth Element has already achieved a cult status, and Gaultier’s costumes still inspire millions of cosplayers around the world. Neither the film nor the costumes have won an Oscar though. Ok, I can understand why the film hasn’t. I love the film to death, it’s still one of my favorites, but I get it.

Had the film been nominated in 1997, it would be competing in the 1998 Academy Awards. And in that year, the competition was particularly tough. The winner of that year’s Oscar for Best Film was a movie you guys might have heard of: it’s called Titanic. ;o) So yeah… I get why The Fifth Element didn’t make the cut as a film.

But to this day, I still can’t understand why Gaultier hadn’t even been contemplated. His work on Besson’s film was inventive. It was imaginative. Most importantly, it was utterly and brutally ORIGINAL. And originality should count for something, right? Especially when we’re talking about original concepts.

That year, the winner for Best Costume Design was… Yep. You know it. Titanic. Of course. Why wouldn’t it be, right? Titanic won everything that year. And you know what? It deserved it.

But here’s something I never understood: what are the criteria for Best Costume?

In my mind, in the case of “period films” (like Titanic), where the director is telling a story that actually happened or that is set in a period that actually existed, the criteria probably have something to do with research, accuracy and authenticity. To all the fashion experts out there, if you’re reading this, am I totally off base? I’d love to hear your comments.

In case I’m right, then how can we evaluate the authenticity and veracity of a wardrobe that doesn’t even exist and/or have never existed? Like the one Gaultier created, from scratch. We’re talking about designs that were entirely conceived and conceptualized in his mind. How do you judge that?

I might have a solution.

You know how there are two awards for screenplay? There’s best adapted screenplay (aka Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published) and best original screenplay (aka Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen).

Well, that’s it then.

There should be an award for best adapted costume (like Titanic) and one for best original costume (like The Fifth Element). This way, conceptual thinkers like Gaultier would have a fighting chance. How cool would that be? Academy, you heard it! Let’s do something about it. ;o)

As we all know, even the most original works are inspired by something (or someone) else.

And a big, huge inspiration in Jean Paul Gaultier’s life was a film called A Clockwork Orange. Gaultier even launched a 2008 Fall Collection inspired by the costumes he saw on Kubrick’s 1971 cult classic. Years later, upon running into Malcolm MacDowell (the actor who played Alex, the main protagonist in A Clockwork Orange) during a film festival, Gaultier told him: “Thank you very much, because that film changed my whole design.”

This was super kind of Gautiler. But the person he should have thanked though was Italian costume designer Milena Canonero. The woman is a BEAST. She’s done it all. The Shining, Midnight Express, Chariots of Fire, The Godfather III, The Grand Budapest Hotel, those are just a few of the movies she has under her belt.

In my humble opinion, though, her work on A Clockwork Orange remains, by far, her best. For obvious reasons: it’s the most original one. It’s also the most conceptual one.

And it’s the one we’ll focus on in the next post!

See you all then.