Dress To Impress (Part 1/3)

/Let’s take a trip back to the best decade ever: the 90’s.

Ok. That’s debatable. Scratch that. Let’s filter it a little bit. Let’s talk music. Musically, I think we can all agree on that, right? The 90s were THE BEST! No decade comes close.

All due respect to the amazing 70s (which blessed us with bands like Rush and Pink Floyd) and the glossy 80s (which graced us with albums such as Appetite for Destruction and Master of Puppets). But they pale in comparison. The 90s were a different beast altogether.

The 90s gave us Tupac, Snoop and Dre on the West; Biggie, Jay-Z and Wu-Tang on the East. The 90s gave us Rage Against The Machine! The 90s gave us Grunge, for crying out loud.

The music scene in the 90s had an undeniable balls-to-the-wall, everything goes, fangs-out, nevermind (Nirvana, anyone?) attitude. Part of me can’t help but think that that was actually a reflection of that decade’s general Zeitgeist. It was such a messy and weird time.

It was also when supermodels became a thing. The 90s ushered a new era in fashion, as the decade started by introducing us to names like Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista, and ended on the highest possible note: by introducing the world to our very own Gisele Bündchen.

Music and fashion seem to exist as two sides of the same coin or two hemispheres of the same brain. You can’t have one without the other. And like most teenagers growing up in the 90s, I used both my musical taste and fashion sense (or lack thereof, actually) to express my feelings, find my identity and make statements.

My weapon of choice was a plaid flannel shirt and baggy jeans. Yep. Not gonna lie. I was a grunge wannabe. The reason i say I was a “wannabe” is because I grew up in sunny Brazil, attending a private German school, under the careful and constant surveillance of my academic-driven Asian parents. So I was the furthest thing from the latchkey kids who were born and raised in (rainy and gloomy) Seattle, pretty much left to their own devices and who REALLY understood what Cobain, Vedder and Cornell were singing about. But somehow, for some superunkown (Soundgarden, anyone?) reason, grunge was my thing.

My classmates also wore according to their beliefs.

Some banged their long hair while listening to Iron Maiden or Black Sabbath. Others wore leather jackets and boots, playing The Ramones or Die Toten Hosen in their walkmans (I know… I’m older than dirt). And then, there were the occasional clubbers, who were into bands like The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers, at a time when no one really understood what electronic music was and… no one really understood what they were wearing either.

In any case, it was during those fun and tumultuous high school years that I came to understand that clothes aren’t just for protection or embellishment.

They’re signifiers.

Just like our favorite songs, bands and albums, our clothes tell stories. They represent who we are, indicate what we’re thinking and symbolize where our hearts are at a particular moment in time.

In other words, our fashion choices mean something.

Concepts have the power to give things a meaning, thus creating value for them. And in that sense, fashion is (and has the potential to be) as conceptual an art form as any other. This isn’t a theoretical conclusion. It’s a statement of fact.

I know this because as an insecure 15 year old, I experienced this power firsthand: seeing other students in the high school halls wearing plaid flannel shirts meant that I wasn’t alone in my teenage angst. And that realization was extremely valuable for me.

Since then, I’ve gained a deeper appreciation for fashion design. I don’t really care about or pay attention to types of fabric, textile technology and whatnot. No offense to all the textile engineers out there, but the truth is that, for whatever reason, that doesn’t interest me.

What does interest me, though, is looking at someone or at a group of people dressed a certain way and trying to understand the whys behind that particular style.

What’s up with that metal chain hanging out of his pocket? Why is she wearing a foulard wrapped around her head? What’s the message behind a certain color or that particular motif on his/her T-shirt? Those are the questions that make fashion interesting for me.

It was also in the 90s that one of the most powerful films I’ve ever watched came out: Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992), starring Denzel Washington in the role of the African American activist. The film left such a lasting impact on me that a few years later, I decided to read the book By Any Means Necessary: Trials And Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X, written by Lee himself and Ralph Wiley.

As the title of the book suggests, Lee walks us through the making of his masterpiece. He discusses the threats he received from the Nation of Islam. He tells us about his epic clashes with Warner Bros over the film’s budget. And he dedicates almost an entire chapter to talk about the meticulous and exhaustive research that went into the design of the sumptuously detailed period costumes shown in the film.

Enter… Ruth E. Carter.

Ruth Carter is a costume designer from Springfield, Massachusetts, and has collaborated with names like Spike Lee (Do The Right Thing, Malcolm X), Steven Spielberg (Amistad), John Singleton (Rosewood, Four Brothers) and most recently, Ryan Coogler (Black Panther).

Ruth Carter is AMAZING. Not just because she won the Oscar for Best Costume Design in 2019 for her work in the Marvel blockbuster Black Panther. Nah. The Oscar is nice. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. That’s not why she’s a creative role model to me.

To me, what makes her such a brilliant and inspiring designer is the way she sees herself as a researcher, first and foremost. The amount of research that goes into every single one of her designs is simply off the charts. It starts at the moment she receives the script and goes all the way to the fitting sessions with the actors.

On her episode of "Academy Originals", a documentary-style video series produced by The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, she takes us inside her creative process in an exploration of where her ideas come from.

First, she talks about how everything starts with the script.

“Generally, I like to read the script and experience the story. (…)

(The first time I read the script) colors pop into my head. I see the palette.

The second time that I read the script, I actually do focus on the image of each character.

And then, the next time I read the script, I’m breaking it down in terms of each individual character. (…)”

In other words, she goes through the whole script THREE TIMES BEFORE she even starts sketching or drawing or designing anything.

Then she proceeds to discuss the last part of the process, which is the fitting.

“One of the aspects of the process that I love is the fitting.

Many times, your board, your illustrations, your color palette, your swatching, all that goes out the window when two artists come together and decide ‘how can I tell this character’s story on me’?

So I spend a lot of time with the actors. Our fittings are generally two hours.

They become, you know, my canvas”.

Which means that even during the fitting session, the last stage before the actual production of the wardrobe, she’s still researching, gathering information, collecting inputs and making final tweaks and changes and adjustments based on that.

You know, some creatives have the ability to come up with the most amazing ideas out of thin air. Seriously, I can’t even begin to fathom how they do it. I’ve known a few of them during my career, especially copywriters. And I’m not ashamed to say it: I really envied them. I was always in awe of how they were able to come up with the wittiest, most powerful taglines… just like that.

I wish I could be like them.

Unfortunately, I’m not.

Instead, I’m the kind of creative that needs to do his research in order to get started. Maybe that’s why I identify so much with Carter’s creative thinking: because I understand what she’s doing. Every time she dives into one of her researches, she’s actually making sure she understands the context first, so that she’ll be fully prepared to come up with concepts later.

Research has an extraordinary and indispensable effect on the creative process: it nourishes the idea and makes it stronger as it adds new depth, further accuracy and more veracity to the concepts.

When you do your research and you do it right, without skipping any steps, when you do it the way Carter does it, by being ruthlessly thorough and careful, something spectacular happens: your ideas and concepts become pretty much unassailable, from an objective standpoint.

Subjectively, of course people will still have the right to like or dislike your idea, no matter how much research you put into it. But if you do your research the way it’s supposed to be done, and they still dislike it, that only means your idea is not the right one (meaning it’s not their favorite); it will never mean it’s the wrong one (meaning it is incorrect).

Let me explain this difference between “an idea that’s not the right one” and “an idea that’s the wrong one” with a real example.

In 2011, the French National Soccer Team changed sponsors. After 40 years working with Adidas, les bleus (the blues) decided to go with Nike. Obviously, Nike’s first assignment was to design the team’s new uniform. And (in my opinion), they knocked it out of the park. It’s just absolutely perfect. I even got myself one (and I don’t even like soccer!). The video below tells us a bit of what went into the design of what would become Nike’s debut uniform of l’équipe de France.

Now, most of the people I know loved the new design. Other didn’t. And that’s ok. Art is subjective. For some people, the idea for the new uniform wasn’t the right one. Which only means that the new design wasn’t their favorite. That’s all. However, say whatever you want to say, call it whatchu-wanna-call-it, but there’s nothing WRONG about the design: the color is right. The emblem is right. Even the phrase printed on the back of the emblem, and that represents the diversity of the French National Team (nos differences nous unissent) is right.

Let’s imagine a different scenario now. Let’s say Nike had done a unanimously beautiful, cool and elegant job with the design of the new uniform. Let’s say EVERYBODY loved it. Here’s the thing though: let’s say that instead of a rooster (France’s official mascot), there’s an eagle. And instead of blue (France’s official color), the color of the uniform is orange.

Let’s say the idea behind the eagle is to represent freedom, or, la liberté. Let’s say that the idea behind orange is to symbolize energy, strength and resilience. They’re all great ideas and they make sense in the context of a soccer team. However, given that the eagle represents Germany’s National Soccer Team and orange is synonymous with the Netherlands, no matter how much people liked the new design, the idea behind it IS WRONG.

See the difference?

If you’re anything like me, that is, if you know NOTHING about soccer, you’re bound to make some mistakes, like using orange instead of blue, and an eagle instead of a rooster. But when you do your research, the chances of making these erros drop nearly to zero.

It’s our responsibility, as creatives, to make sure our ideas are never wrong.

Which is why we have to do our homework AND our research.

The most powerful idea is and always will be the one people are willing to buy, both literally (by paying for it) and figuratively (by believing in it). And people only buy things that are, on some level, valuable to them. They buy things that MEAN something to them. In the case of an ideia – a concept – people must feel like that idea represents them in some way, shape or form.

Carter excels at her craft in that sense. Watch her interviews. Read articles about her. Two words will pop up the most. A noun and a verb: “research” and “represent”. And that creates a very delicate situation for her.

As creatives, the more research we do about a particular subject or project, the more inputs we’re able to acquire, the more knowledgeable we become about it and the more insights we tend to have. As a result, the temptation to create concepts that comprehend everything that was gathered during research is very, very hard to resist. It’s the ego, you know? As humans, we like and want to show how knowledgeable we are about this or that subject.

In other words, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking “but I can’t cut anything out, because everything is important”. When creatives fall into that trap, most often than not, their ideas tend to be so broad and general, that they end up looking like most airports in the world: faceless, insipid and, worst of all, unoriginal.

“There’s nothing more beautiful than a sketch done on a piece of art paper”

Ruth E. Carter

So, how do you know what to include and what to cut out?

What are the criteria?

In an interview she did for Vanity Fair in December 22, 2020, titled ‘Black Panther's Costume Designer Ruth E. Carter Breaks Down Her Iconic Costumes’, Carter gave us a perfect answer to those questions:

“The most difficult part of being a costume designer is that (…) you’re in the background AND you’re in the foreground (…). There are lots of people and layers to creating a costume – from getting a person dressed for the set to communicating ideas – that I’m constantly paring it down.

We all want to take the lead, and show our stuff, and be out front, and (go): look at me! Look at me!” But a lot of times it’s: ‘DON’T look at me!’ A lot of times it’s: ‘let’s be subtle’.

Believe it or not, there IS a dialing down and a constant understanding of the bigger picture, the composition.

And I have to consistently be aware of THE INTENT and composition of each scene”.

In other words, it’s not about her. Much less her ego. It’s not about showing the director how much she knows about the subject. Carter Said it herself: it’s not about “look at me, look at me”. It’s about “don’t look at me”.

To her words, I would add this: “Don’t look at me...Instead, look at the scene. Focus on the character. Pay attention to the story being told”.

Once the research is done, that’s how you decide what makes the cut and what doesn’t. You have to ask yourself: WHY am I including this?

Think of it this way: costumes cost (a lot of money), so whatever detail you feel like adding to them, whatever changes you feel like making, needs to be justifiable. The studio, the director, the production company, they’ll want to know why you’re adding this or that detail, why you’re changing this or that color, why you’re designing the costume this or that way.

And if you’re thinking conceptually, “because it looks prettier” is not and will never be an acceptable answer.

There has got to be a reason why.

Every piece of clothing (from tiny accessories to elaborate suits) needs to have a meaning. Every detail (from texture to size to color) needs to have significance. The costumes must represent something specific. They must serve a specific purpose on the film.

Sometimes, the goal is to inspire and highlight a character’s line. Other times, the aim is to show us who the characters are, where they come from, and how they relate to each other.

Carter is probably one of the most conceptual costume designers ever in that sense. Her costumes tell stories of their own. And every single one of these stories plays a role not only in the composition of a particular scene, but also in the overall narrative of the film. Here’s a perfect example of Carte’s conceptual approach.

In Malcolm X, for instance, Carter invites us to revisit three different stages of Malcolm’s life by presenting us with different costumes.

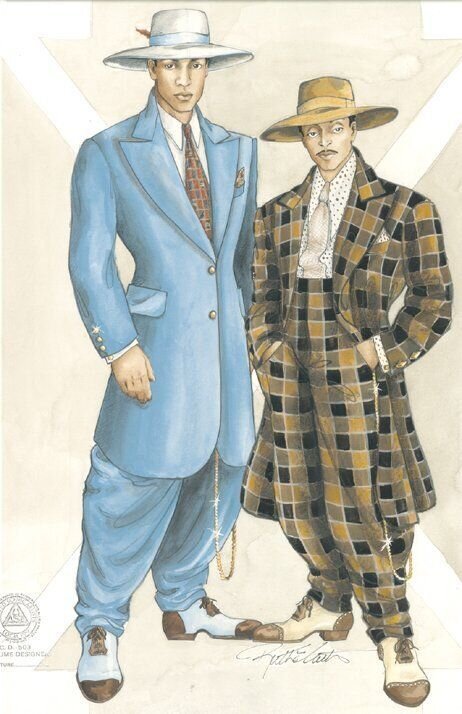

First, there are the colorful, bright, extravagant zoot suits that represented his period as a street hustler as well as his state of mind at that particular time: a man ruled by his ego, filled with vanity and full of swagger.

Then there are the ton-sur-ton blue denim uniforms from the time he was incarcerated in Massachusetts. Carter deliberately toned down the color palette during the prison scenes, since the intent of those scenes was to depict a colder, sadder and – later on – more pensive and contemplative part of Malcolm’s life.

With that transition, from the vibrant colors of the zoot suits to the pale and washed-out blue of denim uniforms, Carter meant to show Malcolm’s own transition from an impulsive young man looking to make money illegally to a calm, religious, well-educated and articulate grown up man.

And finally, there’s the suit Malcolm wears during his first meeting with Elijah Muhammad. As Carter describes it, “the suit is old, oversized and a little rumply”. That was not by chance. It was intentional. That suit, which Carter called “one of the costumes I’m really the most proud of” signified Malcolm’s humility. It showed us that he was a changed man after prison. The vanity and self-obsession represented by the zoot suits were gone.

Carter went the distance (as she always does) in her research for Malcolm’s costumes. In her Netflix episode of the Abstract series, for example, she talks about how far she went when she was designing Malcolm’s zoot suits.

“I researched exactly what the length of the coat was, how narrow the pant was, what kind of chains went around, what kind of pocket watch, how long the feather would be so that we could really get a true sense of what a zoot suit looked and felt like to wear”.

She didn’t spare any punches either when it came to designing the prison uniforms and the suit Elijah Muhammad’s meeting suit.

“I wanted to know a lot more about Malcolm X, the man. Since he was incarcerated in Massachusetts at the Department of Corrections, I did a letter writing campaign to them asking to see his file.

I had medical records, his booking photo, and I had quite a few letters that he had written. And I noticed how his penmanship changed, and his grammar increased as he educated himself. I got to know a little bit more about Malcolm X through his writing.

And I felt like this was important, since I was going to be creating his wardrobe in times where we didn’t know him and we didn’t see him in photographs. And I wanted to be able to make those decisions that I felt were critical to telling his story.”

See? I told you. When I said Carter is a researcher first, I wasn’t lying. Who goes as far as checking medical records to design and create a costume? But she didn’t go through all that just because. There was a very clear purpose behind her efforts. And the purpose was to tell Malcolm’s broad and multi-faceted story right. For every period of his life, in every scene, there was intent.

Carter is not the only one to create things this way in the fashion world. In the next post, we’ll get to learn more about other amazing, incredible costume designers who approach fashion in much the same way Carter does.

Conceptually.

See you then!