The Indestructible House

/Hi, my name is Eugene, nice to meet you.

Now, let’s be honest. That’s kind of a strange name, right? I think so. Given the fact that I was born and raised in Brazil, I still can’t figure out why my parents chose this name. I also can’t remember how many times I had the following conversation throughout my life:

Someone: Hello, what’s your name?

Me: Eugene

Someone: Oh, Eugênio (which is Eugene, in Portuguese)

Me: No, Eugene.

Someone: Come again?

Me: Nevermind. Eugênio is fine.

As I grew older, I came to realize that not only is Eugene a pretty odd name, but it seems like there’s an inherently odd component to it too. Somehow, if there’s the name Eugene on it, it’s probably a bit weird. There’s probably something eccentric or unorthodox about it. As one of my fellow Eugenes once said, “You can never get too cool with a name like Eugene”.

The person who said that is a Canadian-American guy called James Eugene Carrey. He’s an actor. And also goes by the name of Jim Carrey. Yep. That Jim Carrey. The Mask. That one. On May 15th 1994, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he was talking about how embarrassed he felt being a movie star and all and this is what he said.

“My life is a string of embarrassing moments. I’ve gone to premieres and tried to make the cool-guy exit, and the limo driver locks the keys in the car, and it’s running, and he’s trying to pick the lock while I’m standing there and the whole theater is emptying out.

I call it the Eugene Syndrome, because my middle name is Eugene. I always figured my parents named me that to keep me humble. You can never get too cool with a name like Eugene."

Jim Carrey starred in the 2000 film called “Me, Myself and Irene”, directed by the Farrelly brothers, where he plays a state trooper named Charlie, who suffers from a split personality. On the one hand, we have Charlie, who’s super sweet and gentle. On the other hand, we got Hank, Charlie’s unhinged, over-the-top alter ego.

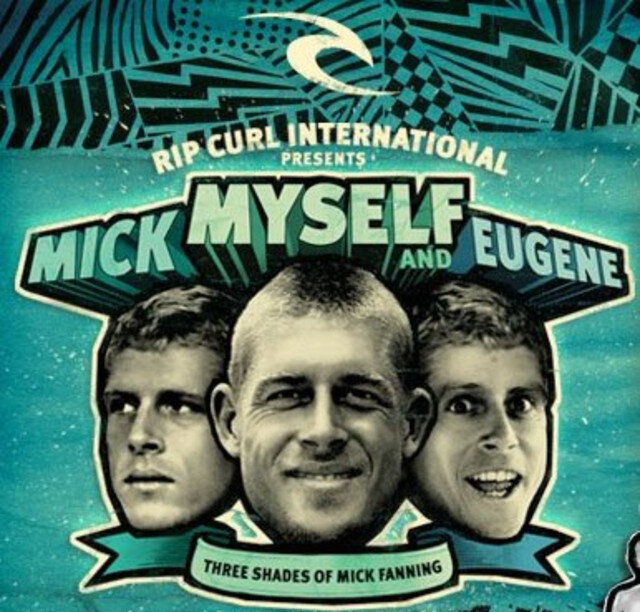

Five years after Jim Carrey’s film came out, in 2005, another one of my favorite Eugenes launched his own movie (a documentary, actually), called “Mick, Myself and Eugene”. I’m talking about the fastest surfer ever and three-time Surfing World Champion, Australian Michael Eugene Fanning, best known as Mick Fanning.

The documentary shows us three sides of Mick, with Mick being the laser-focused competitor, “Myself” being the spiritual free surfer and Eugene being the fun-loving, crazy party animal. Not surprisingly, Eugene is the one who gets out of control and, thus, tries to throw a wrench in the works of Mick’s stellar competive surfing career and tries to break “Myself” out of his Zen.

Good things come in threes, so let’s take a look at a third and last example and we’re done, ok?

There’s this thing called Theater of the Absurd. Ever heard of it? It’s an artistic movement of the late 50’s, in which plays told stories about the human condition, swinging back and forth, existentialism on one end, nihilism on the other. You know, off-the-wall kind of stuff.

That being said, I guess it will come as no surprise when I tell you that one of the most prevalent characteristics of this movement was that nothing seemed to follow a logical train of thought and everything felt completely nonsensical, from the theme to the dialogue between characters. Come to think of it, there’s a reason the name of movement had the word “Absurd” in it.

And it just so happens that one of the biggest icons and greatest writers of this particular movement was a guy who was born in Romania but grew up in France. He was a playwright. His name? Take a wild guess. What name rhymes with absurd? That’s right. Eugene. But the guy was French, so it was actually Eugène. His full name: Eugène Ionesco.

I rest my case.

The reason I brought these quirky, idiosyncratic Eugenes up is because I wanted to warm you guys up before introducing you all to one of our most eerily unconventional, intelligent and talented namesakes out there: Chinese-American architect Eugene Tssui (pronounced t-sway).

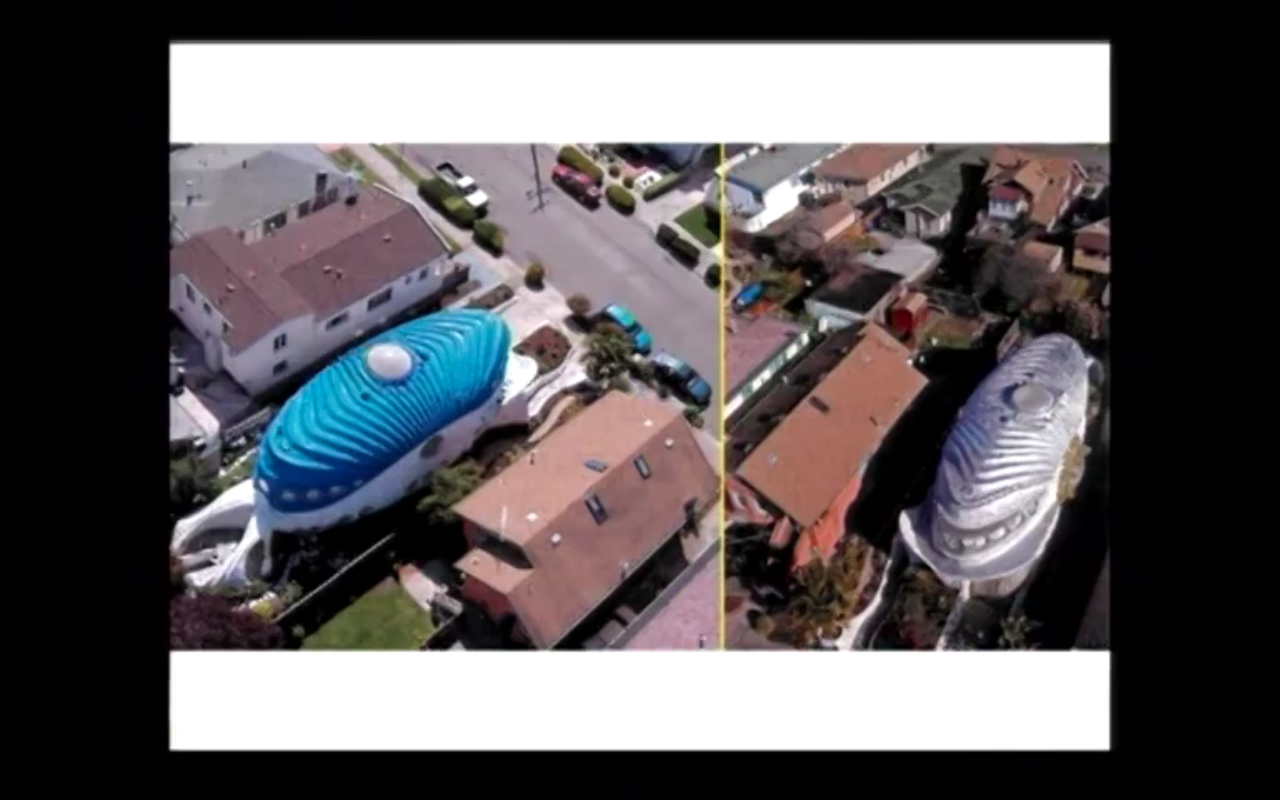

He’s the mind behind the famous (and outlandish) design of the Fish House, located in the city of Berkeley, California. The house doesn’t look like a fish, so to this day I don’t know why it’s called the Fish House. It is also known as “Ojo del Sol” (which means Eye of the Sun, in Spanish). Given that it doesn’t resemble an eye, much less the Sun, I also have no idea where the name comes from.

Have you guys ever watched a series on Netflix called The Good Place? It’s amazing, and I highly recommend it. Anyway, there’s one particular episode where one of the characters says he has what doctors call “Directional Insanity” claiming “he once got lost on an escalator”. That’s me. I have that. I can’t read maps. I get lost everywhere. And I think Waze is the best invention ever. ;o)

The first time I saw the “Fish House” was because of my directional insanity. I came across it by accident. It was in 2001, I was a student at UC Berkeley and I was driving down San Pablo Ave, trying to get to Ashby Ave. They intersect, so all I had to do was drive straight. Yet somehow, I got lost and I ended up on a street called Matthews, which is where the Fish House is located. More specifically, 2747 Mathews St.

When I first spotted it from afar, I couldn’t believe my eyes. It looked otherwordly. First, I thought it was a house built in the shape of a mushroom. Then, I passed in front of it again and, this time, it sort of resembled a snail shell. I drove past it a third time and this time around, for some reason, my brain interpreted it as a Nautilus’s shell cut in half, transversally. Anyway. You get the point. It was weird. Peculiar. Most importantly, it was totally and completely original.

Dr. Eugene Tssui, like most Eugenes (myself included), is a bit of a weirdo and, thus, kind of a misfit. It’s hard to describe the man. Some people call him genius. Others call him visionary. Most call him a polymath.

Personally, I see him as a sort of Asian Ziggy Stardust, taking his Spiders from Mars on a crazy Journey To The Center Of The Earth, Rick Wakeman blasting on the background and dreams of Picasso, Matisse and Charisse floating on his mind.

He’s an athlete, but also a musician. He’s a martial artist who does Flamenco. He’s an Olympic medalist and an award-winning designer. People say he comes from another planet and he’s ok with that. He’s an eight-time world amateur boxing champion. And when his hands aren’t punching people to a pulp, they’re playing Chopin on the piano.

Academically, his path is also very unique. He was expelled from Columbia University Master’s Program because, according to the dean of the architecture department, “they couldn’t teach him what he wanted to learn”. So, he kicked the East Coast to the curb and headed west.

Started his Masters again, this time, at the University of Oregon, which is located in the city of Eugene. That’s right. Eugene, Oregon. Now, with a name like that, you’d guess he’d be embraced – or at least accepted – there, right? Nope. He was expelled again, only this time, it was due to “conceptual differences”. See? I told you. Eugenes are weird.

Finally, he ended up at UC Berkeley (go Bears!), the “home of the Free Speech Movement”, where his unusual approach and his imaginative work were not only tolerated but also encouraged.

Tssui is of Chinese descent (his parents have roots in Beijing and Shanghai) but identifies more with Mongolia. So much so he says the reason he added an extra “S” to his last name is because Temüjin (Genghis Khan’s birth name) told him to do so. Yep. Somehow, Tssui not only listens to Genghis Khan, but apparently they’re so tight, he gets to call the founder of the Mongol Empire by his birth name.

Speaking of Tssui’s parents, Florence and William Tsui, they are the reason Eugene designed and built the Fish House. He wanted to build them the safest house ever, one that would be impervious to fire, storms, hurricanes, floods, earthquakes and every other kind of Natural disaster. He wanted the house to be indestructible.

Being a ferocious advocate of the principles or Evolutionary Architecture (he even wrote a book about it, called Evolutionary Architecture: Nature as a Basis for Design), he looked to Mother Nature for inspiration and advice. As most conceptual thinkers do, he started his creative journey by asking questions.

And the first question he asked was: what is the most indestructible living being in Nature?

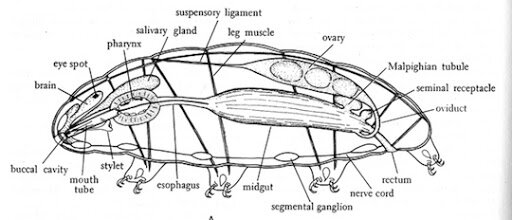

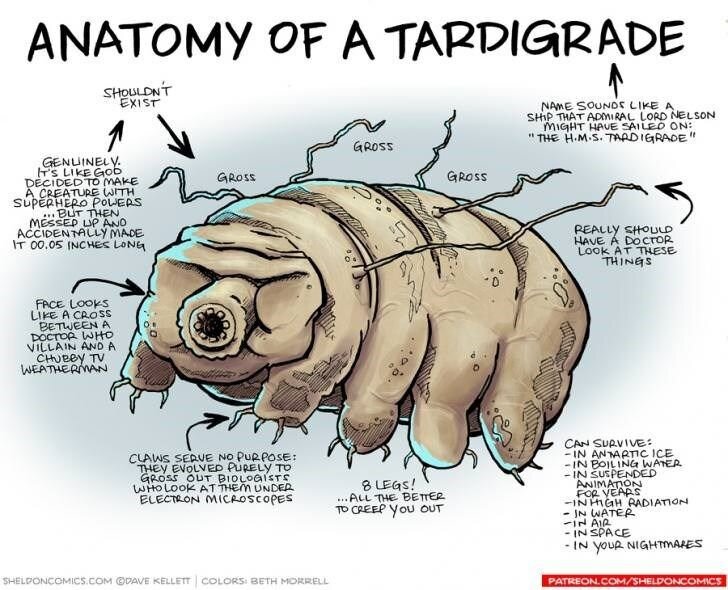

The answer: the tardigrade.

The tardigrade, also known as “Water Bear” (come on guys, if that’s not the most adorable nickname ever, I don’t know what is), is a microscopic eight-legged animal, virtually invisible to the naked eye. You know how some people say that if someday a nuclear cataclysm puts an end to the world, cockroaches would be the only survivors?

I don’t know if these people are right or wrong. But I do know this: if ever there were an apocalypse strong enough to wipe out even the cockroaches that survived, tardigrades would still be chilling. Sunglasses on. Sipping on gin and juice, with their mind on their money and their money on their mind. ;o)

Here’s how a 2015 BBC article described them: “Boil them, deep-freeze them, crush them, dry them out or blast them into space: tardigrades will survive it all and come back for more”. But let’s get into more details, shall we? What exactly does that mean, “boil them”, “freeze them”, “crush them” etc?

Well, according to the National Geographic website, tardigrades can survive temperatures that go from −272.95 °C (that’s almost zero Kelvin, guys!) up to 150 °C. They can withstand pressures six times that of the ocean’s deepest trenches. That’s six Mariana Trenches, one on top of each other. Believe it or not, there’s more.

They can also spend up to 30 years without food or water. They’re capable of resisting incredibly high doses of radiation (from X-rays to ultraviolet radiation). And if that wasn’t enough, in 2007, they were sent to space, spent 10 days being exposed to conditons that would kill any human in a matter of minutes, and came back as if nothing had happened.

All that toughness has an explanation though. The reason why tardigrades are able to survive such extreme conditions and environments is its ability to enter into a state of anhydrobiosis. The word comes from the Ancient Greek, hydro meaning water, bíos meaning life and the prefix an- meaning not.

In that state, tardigrades squeeze all the water out of their bodies, retract their heads and limbs, roll up into a little ball (called a tun), and become dormant. Without water, they become wrinkled like a raisin. Most proteins need water to work, so to protect their proteins, tardigrades basically turn their insides into glass (!). And that’s it. Now, they’re basically dead. They’re just there, their bodies stopped in time, waiting for the conditions to improve, so they can unfurl themselves and go about their business.

In other words, Tssui designed a house for his parents based on the Chuck Norris of the Animal Kingdom. ;o)

Now, on the pictures below, please - from left to right - follow the sequence.

First, let’s take a look at the Tardigrade, the animal.

Then, let’s check the croquis designed my Tssui’s Design and Research Company.

Finally, let’s see the finished product, the Fish House itself.

You can see that - from animal to croquis to building -, the shape and the external appearance of the Tardigrade are somewhat preserved, right?

In some circles, that’s called Biomimetic Architecture (the name is self-explanatory).

Given his passion for Nature, at first, I thought Tssui would be one of the greatest examples of biomimetic architects. I was wrong, though. Ironically, he is one of the harshest critics of this school of thought.

In a 2012 interview for the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), Tssui explained to American physiologist Scott Turner why he doesn’t consider himself a biomimetic architect. It’s in the video below (7’00” – 12’00”).

“Those architects are just copying the shape and form, the external appearance. They’re approaching architecture as a decorative form. And that’s the opposite of what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to understand WHY that form was built the way it is. (…)

Beyond that, I’m also trying to understand how these concepts in Nature can be utilized for everyday purpose. (…)

I’m not just copying shapes for the fun of it. I’m not saying ‘oh, so this is biologic design, so it looks like a fish, or it looks like a tardigrade, or an eel. That’s not what I’m doing. I’m trying to understand the thought behind the creation of these living things. And then, trying ways to apply those concepts, those thoughts. (…)

I’m trying to understand the whole process of the structure.

The REASON for it. Not just the appearance.

And that’s a big difference.”

“I’m trying to understand WHY that form was built the way it is, (…) understand how these CONCEPTS in Nature can be utilized for everyday purpose, (…) understand THE THOUGHT BEHIND the creation of these living things. I’m trying to understand the whole process of the structure. The REASON for it. Not just the appearance.”

Yes, Tssui is an architect. But first and foremost, he’s a conceptual thinker.

What interests him is the ‘whys’ of the process. It’s the reason why something is being done the way it’s being done.

It’s the thought behind the creative endeavor. He doesn’t look at an animal or a plant and thinks form first, function later.

Eugene Tssui thinks function first, form later.

Need a roof that allows ventilation and warmth as needed? (Function)

Easy. Let’s build a hinged retractable roof inspired by dragonfly wings. (Form)

Boom. Welcome to the Reyes Residence in Oakland, California.

Looking to minimize carbon footprint and utility bills? (Function)

No worries. Let’s build 10 wall panels that open and close according to the changes in temperature, humidity, climate and natural light. Mmm. Let’s see. What opens and closes as needed in Nature? Oh, yeah. Of course: the Venus flytrap. (Form)

Boom. Welcome to the ZED Residence in the foothills of Mount Shasta, Northern California.

In the case of the Fish House, the goal was to build the most indestructible house ever (Function).

And the answer was the Tardigrade. (Form)

The Tardigrade has an oval shape. So, by curving the outline designs of the house, Tssui wind-proofed it. Ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 mm, the Tardigrade has a pretty compact body plan and kind of looks like a single cell organism (even though it isn’t). So, all floors, walls and ceilings of the Fish House were built in one unit, because this kind of continuous construction dissipates the force of earthquakes tremors on the house.

California is known for its raging fires. So the Fish House needed to be fireproof. The only thing is that, by now, we all know Tardigrades can sustain incredibly high temperatures, but they’re not fireproof. So…now what?

Well, luckily, by now we also know that when it comes to conceptual thinking, function always comes first. The form is there to serve the function, not the opposite.

And if function comes first and, in that case, the form of the Tardigrade couldn’t serve the function of fireproofing the house, Tssui needed to find a different solution. Which he did. And it came in the form of a cactus (ahhh…Mother Nature never disappoints!).

Some cacti are known to be fire resistant, because of the total amount of moisture they contain relative to their dry weight. Much like a succulent plant, cacti have the ability to store water, which means they don’t ignite or catch on fire very easily. In addition to that, some cacti can even close their pores to prevent excessive water loss.

In other words, the inner structure of some cacti isn’t shallow. It’s quite the opposite, actually. They’re packed with water and try everything to remain this way. Inspired by that, Tssui used blocks of recycled Styrofoam cups strengthened with concrete and steel rods to build the Fish House. And the Styrofoam blocks are so packed together; no air can get through, making them fireproof. The plastic coating ensures they’re also waterproof.

On the last post, we’ve seen how a croquis – conceptually speaking – is not a rudimentary version of the final project, but instead, the synthesis of the final project. That’s the case with the Fish House.

Outside, it’s not just the shape of a Tardigrade; it’s its essence.

Inside, it’s not just the structure of a cactus skeleton; it’s its essence.

In other words, there’s a reason behind every element that went into the Fish House.

Every window, every ramp, every shape, every decision, there’s a reason-why behind it.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit it: aesthetically, all three buildings (the Reyes residence, the ZED residence and the Fish House) look super alien, even though they were all inspired by Mother Nature. Some of you guys might find their appearance way too unusual. Some might find them scary even.

But that doesn’t take away the fact that, no matter how we feel about them, they are and, to this day, remain impossibly original. And “impossibility” and “originality” seem to be the main driving forces behind Eugene Tssui’s unrelenting inquisitive brain.

“There’s something about things that have never been considered. True success happens when you’re doing something that has never been considered before. That’s when you know you’re on the right track, because you have originated something new. (…) You contributed something to the consciousness of possibility. (…) You’re making the impossible possible. That’s when you know that you’re doing something significant”.

This excerpt came from a video published on September 22, 2020, titled “A Spontaneous Conversation with Dr. Eugene Tssui”, which you can watch below. If you’d like to jump straight to it, please start at 7’00” until 11’00”.

Ok, enough is enough. Time to come clean.

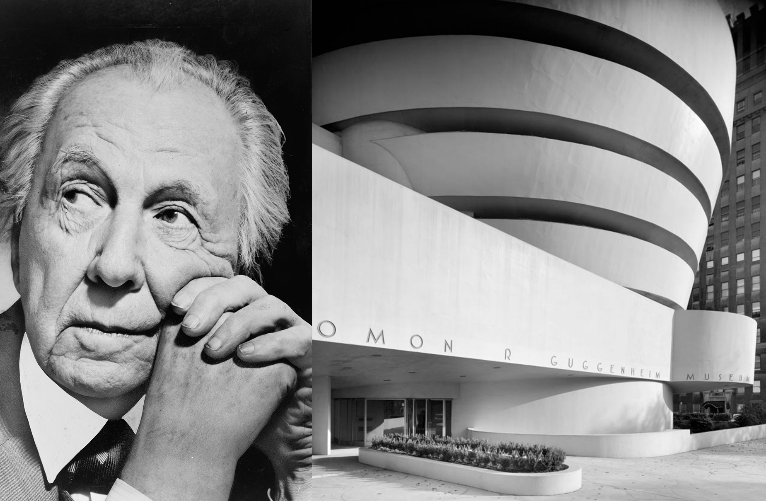

I’ve been writing this endless text about Tssui and his designs and all, but the truth is I don’t know anything about architechture. I mean, anything. All I know are the names of a few famous buildings and a few famous architects. One of them is a guy named Frank Lloyd Wright (a name that, to this day, I mistake for Andrew Lloyd Webber, the composer). I know… NOT COOL! Then again, my name is Eugene, so… what did you expect? ;o)

Frank Lloyd Wright is considered one of the greatest architects in History. His career spanned over seven decades. That’s SEVENTY YEARS of creative work, designing buildings such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in NYC.

Now, with that kind of experience, talent and legacy, I think it’s safe to say the man probably knew a little bit about how to spot creativity, right? That being said, according to a 1951 edition of Life Magazine, one of the few American architects Wright considered truly creative was a guy called Bruce Goff.

And when Wright says a guy is creative, the least one can do is give him the benefit of the doubt. You have to go check, if only for your own edification. So I did. I googled “Bruce Goff” and read about him. I’ve seen some of Goff’s work. And I assure you guys. He’s beyond creative.

The man was a nutcase. He was also Eugene Tssui’s mentor.

Eugene Tssui was Goff’s apprentice for six straight years.

During Tssui’s formative, post high school years.

It’s all making sense now, huh?

Extraordinary. Genius. Brilliant. Wild. Creative. Experimental. Innovative. Those were and are some of the words used to describe Goff and his body of work. However, the adjective that is most commonly associated with him and his legacy is ORIGINAL.

His emphasis on originality mirrors the value and importance he placed on conceptualization. A 2011 article written by Arn Henderson “Teaching The Organic” shows us how Goff saw the creative process and the role concepts played in it. As Henderson tells us:

“Goff insisted that students had “the right to have their own ideas.”

Yet, they were also encouraged to be curious and keep an open mind in conceptualization. They should not be afraid to try other things. There was no form, color, or texture that should be taboo. But as the seed of an idea developed, recognizing and understanding the order within that idea was imperative. (…)

The only way one could achieve originality, and the potential for richness and variety of expression, was by a critical understanding: achieving order in a design was dependent upon the discipline of rejection of all that was not true to the idea. It was through a process of discovery that one arrived at an honest expression.

This was the meaning of Goff ’s oft-used statement of design as “discipline in freedom.” Ultimately, creativity would only be achieved through intuition, rational thought and the discarding of ideas that did not sustain the order of the initial concept. (…)

In his view, it was imperative to acknowledge the developmental order in the moment of the present. A conceptual idea had a life of its own and must be nurtured”.

What Goff is saying is that it’s all about the concept.

It starts with it.

And ends with it.

And if there ever was a student that took that philosophy to heart, it was Eugene Tssui. And I can prove it: in the same 2020 video “A Spontaneous Conversation with Dr. Eugene Tssui” posted above, here is what Tssui had to say about the “conceptualization versus the actual making” of the Fish House.

“It’s interesting because when I designed this building it was a real search. It was a solution to many problems that I was given by my parents and other people and the environment itself. But the actual making of it and the result is kind of anti-climatic because you’ve already thought about it.

So it’s the PROCESS OF CONCEPTION that’s really the time when you’re creating something that seems to be impossible and making it possible.

Once you start to draw it all out and think about it and work out the details, then it’s almost - for me –, it’s almost a kind of anti-climatical process because you’ve already thought about it, you know what it’s gonna look like when you finish. (…)

The conception is the most empowering part of creation.

So it’s all about the concept: the power of the concept, the quality of the concept.

It’s not so much the result in the three-dimensional realm. (…)

That’s the irony of it. You’re trying to grasp for this “making the impossible possible”. And then, when it becomes possible, you’ve already thought of it, so it’s just a matter of making that thing happen.

It’s the irony; it’s the paradox of life. It’s that we always look for the greener pastures and then when we arrive, we think “oh man, you know, I really remember those days when I was struggling and it was so much fun to be a part of that struggle”.

Now, I’m not saying that we should revert to those days and that we should all just be in pain and struggle, but I am saying that once you dream of the concept, that really is the most attractive part of the whole process”.

“It’s the PROCESS OF CONCEPTION that’s really the time when you’re creating something that seems to be impossible and making it possible. The conception is the most empowering part of creation. So it’s all about the concept: the power of the concept, the quality of the concept.”

Goff is probably in Heaven, smiling right now, proud to have taught his student well.

I know I am. Smiling, I mean. Because when Tssui shared those words, it was the first time I heard someone verbalize what I have felt for years (decades, actually), but never knew how to explain: that the conceptualization process is what really, truly matters to me. Somehow, once the conceptual idea is born, everything else seems… incidental. It sounds bad, I know, but that’s how I feel.

Perhaps that’s a different kind of Eugene Syndrome. You know: only caring about the concept and nothing else. Go figure. As some of you guys probably know, the name Eugene means “well born”. So maybe that’s what it is. Maybe what interests us is that unique, special, irreplaceable moment, when nothing becomes something. When the impossible becomes possible. When a blank page becomes a croquis.

The moment when an idea – a concept – is born.

Hopefully, well born.

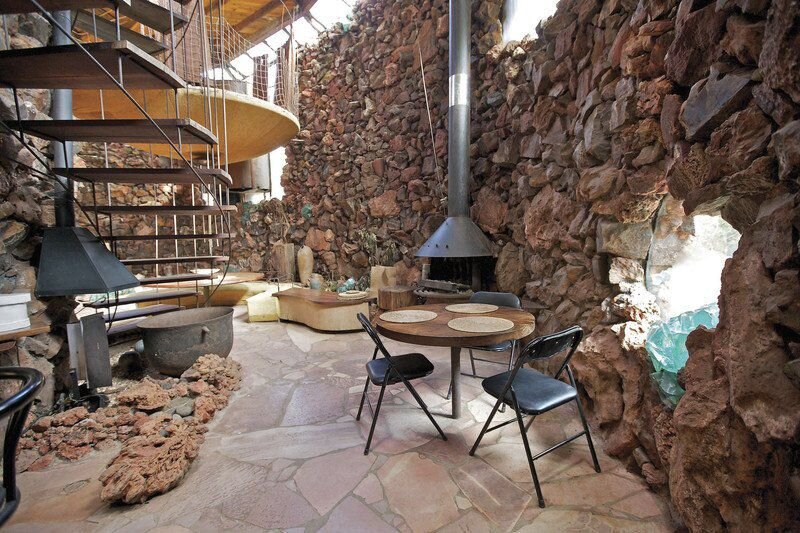

Ps: FYI, one of Goff’s most iconic buildings is a house known as the Bavinger House, located in Oklahoma. Here are a few pictures. Given how (literally) twisted the house is, can you guess the name of its owner? His last name was Bavinger. Now, guess his first name. I’ll give you one try. ;o)