Stream of Consciousness

/About three weeks ago, I wrote a post about Netflix’s The Stack, in which we mentioned Plato, the guy from the cave. Remember how we discussed the “Theory of Forms”? It’s Plato’s theory about how the universe is comprised of “forms” and “particulars”.

Then, a couple of weeks ago, in the post I wrote about the meaning of the Chinese word 概念化 (Gài Niàn Huà), I told you guys about how – unlike my mom –, I never really saw the word “project” as synonymous with the word “concept”.

I spent the past two weeks dwelling on it.

And I came to a conclusion.

In my eyes, the words concept and project are not the same thing. To me, concept is one phase of the project. It’s a PART of the project. Which part, specifically?

It’s the intellectual, immaterial, intangible and abstract one.

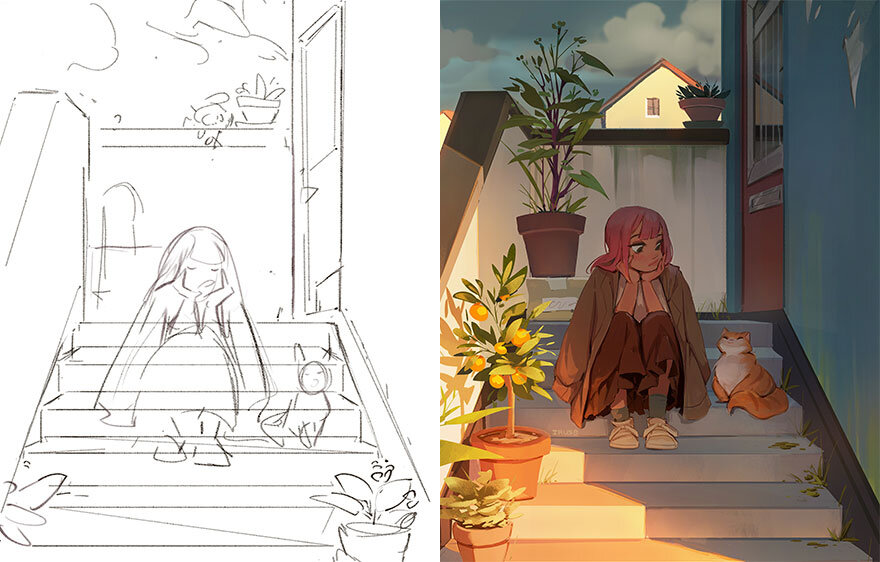

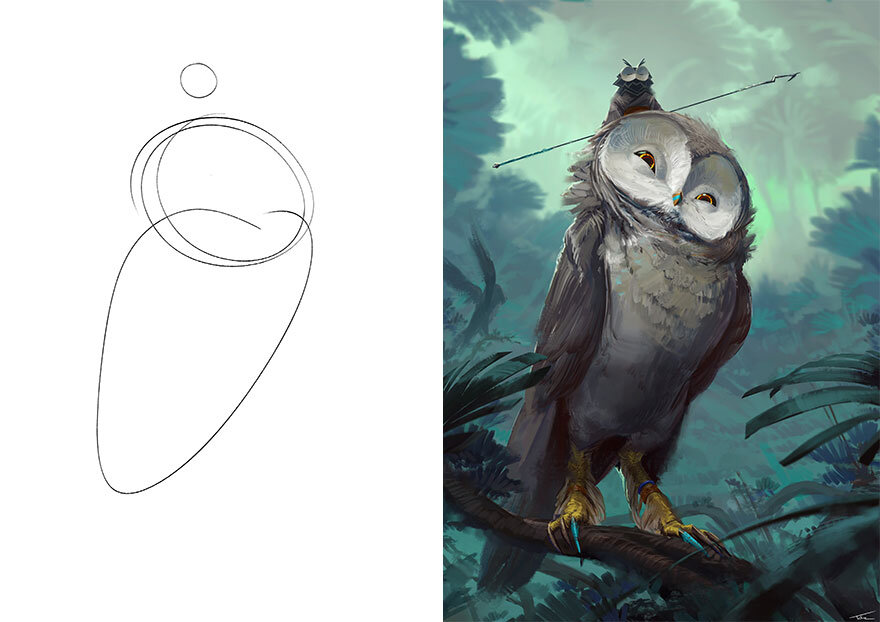

The conceptual part of the project is where everything is born: from the croquis of a new clothing design or a new architectural house plan to the sketches of a new sneaker model or a new sci-fi movie creature.

Croquis is a French word. According to the Larousse dictionary, it literally means: “dessin rapide dégageant, à grands traits, l'essentiel du sujet, du motif”. You don’t need to understand the whole thing. Just the word highlighted in bold. Essential.

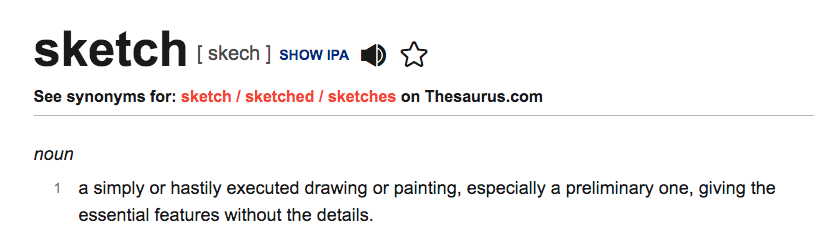

Sketch is an English word, and the definition found on the dictionary.com website is this: “a simply executed drawing or painting, especially a preliminary one, giving the essential features without the details”. Once again, don’t worry about the whole thing. Focus on the word highlighted in bold. Essential.

And why is the concept so essential?

Because it is in the conceptual phase of a project that things begin to form.

I’m using the word “form” here in the same way Plato did. It’s when we access the “realm of the forms”. The world of ideas. This is when a blank page comes to life. When outlines are drawn, without much attention to detail. And random words are written, apparently with no rhyme or reason.

The conceptual phase is the one where creatives engage themselves in a kind of internal monologue. Their experiences, memories, knowledge and repertoire are accessed in what seems to be an incomprehensible and unconventional brand of stream of consciousness.

That’s a pretty neat expression, ain’t it? Stream of Consciousness.

I am not sure how to explain what this expression really means. Some people define is as a sort of flux in consciousness. Others call it a line of reasoning. Then there are those who see it as a flow of thought. I still don’t know which definition I like the most (or if I like any of them at all), but I do know when was it that I first saw those three words put together. Stream. Of. Consciousness.

It was when I got myself a copy of the Train of Thought album. It was released in 2003 and it’s the 7th studio album recorded by American progressive rock band Dream Theater. Stream of Consciousness is the title of the 6th track of the album and it’s a beautiful, almost 12 minutes long, instrumental masterpiece. (I know… 12 minutes!? Then again, it’s a prog-rock band. What did you guys expect?)

I’m bringing this album up because, funnily enough, I think the best definition of Stream of Consciousness is precisely what happens throughout this 12-minute track. Click here, listen to it, and you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about.

A bunch of scrambled notes and chords, coming from 4 different instruments (bass, guitar, keyboards and drums), flowing in a seemingly chaotic and anarchical way, back and forth, fast and slow, sometimes with a heavier approach, other times with a lighter one, all of that unfolding in the midst of countless time signature changes. And yet, somehow some way, in the end, everything makes sense.

In a nutshell, that’s pretty much what the conceptual phase of a project is.

A bunch of scrambled information and thoughts, coming from 4 different sources (experiences, memories, knowledge and repertoire), flowing in a seemingly chaotic and anarchical way, sometimes simply passing us by, other times catching our full attention; occasionally with a stronger punch, every so often with a lighter touch, all of that unfolding in the midst of countless idea exchanges. And yet, somehow some way, in the end, everything makes sense.

Here’s an easier way to explain it.

Imagine you decide to take a picture of a fashion designer or an architect working on a croquis; or maybe of an art director or an illustrator scribbling a sketch. Then, you decide to post this picture on your Instagram account. How would you caption it? Well, instead of the good old “Genius at work”, maybe go with this one: #StreamofConsciousness. It works much better. It conveys the exact same message. And it sounds a lot fancier. ;o)

Most people think the conceptual part of a project – the part where croquis and sketches are born –, is the “part reserved for drafts, scribbles and roughs”. And they’re right. That’s exactly what it is. There’s a “but” though. And it refers to the value and importance that should be given to the conceptual part.

If we only think about and focus on whatever is actually drawn and literally written on that piece of paper, no matter what it is (it may be a house, a piece of clothing, a sci-fi creature or a pair of sneakers), then the idea conveyed by the words sketch and croquis is that of “a rudimentary version of the final project”.

But… when we realize that that scribble or that rough is actually the tangible representation if an intangible, unique and inimitable Stream of Consciousness, then the words sketch and croquis acquire an entirely different meaning. They expand. They become more valuable. Now, the idea conveyed by these words is that of the “synthesis of the final project”.

Try to build a house, sew a piece of clothing, manufacture a pair of sneakers or draw a sci-fi creature WITHOUT CONCEPT. Is it doable? Of course it is. However, the final result will be, most likely, more of the same. It will be just another house. It will be just another piece of clothing. It will be another sci-fi creature like so many others created before. It will be another pair of sneakers, just like every other pair in the world.

That’s why the conceptual phase of a project is so important. So…essential.

Because it is during this phase that the truly, really original ideas are born. The most disruptive concepts. It is during this moment of creative introspection that the artist finds permission to test, experiment and explore freely. It is precisely during the project’s conceptualization that the Stream of Consciousness meets the perfect conditions to reach its most abundant and powerful level.

In our next posts, we’ll see some examples of works that are considered unique, iconic and original. Works that not only changed the world, but the way we see it and interact with it.

We’ll revisit the contexts in which each one of these works was conceived. We’ll learn a little bit more about the artists that created them. And, finally, we’ll discover the sketches and croquis that gave birth to them.

As you’ll see for yourselves, sometimes, the final project and the final result may not have the exact same form (as in “aspect”) as the one originally proposed in the sketch of the croquis. That happens. Every project goes through adjustments, changes and refinements.

However, as you’ll also see for yourselves, still, it is perfectly possible to recognize that the final result of each project, somehow, has the same “form” (in the platonic sense of the word) as its respective sketch or croquis.

That happens because the essence of the project is still there.

Literally, in the form of a concept.